|

Donath provided a thorough look at the murder of Zura

Burns. Zura Burns was born in Missouri, which was also Zura’s real

first name. She was a seamstress and domestic in the house of Orin

Carpenter, who figures highly in this drama.

When Burns came to work for the Carpenters she was living in Lincoln

with her married sister. The sister and her family eventually moved

to the Dakotas. Donath said Burns had no roots or family in the area

once the sister moved.

In the early morning hours of Monday, October 15, 1883, Mrs. Patrick

Dewitt was making her way through town to her family’s farm ground

north of town. Mrs. Dewitt came across Zura Burns’ body, and she

screamed, which brought others out.

The sheriff and coroner were soon notified, and they

called two doctors to come out to the scene. They all started their

investigation. Initially, Donath said they did not know whose body

it was.

The woman’s throat had been cut deeply, so she had bled out. She

also had head injuries from a blunt instrument, which rendered her

unconscious.

When they moved the body once the scene had been examined, Donath

said many people had walked through the area. There were footprints

all over the place, so it was hard to tell whose footprints were

whose.

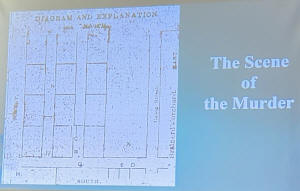

Edward Rottenberg drew a sketch of the murder scene

for the court to view and the location of the body is marked with a

B. Donath said the road was near Union Street, Brainard’s Orchard

and 17th Street. Today, 17th Street is known as Woodlawn Road.

An 80-acre cornfield was also nearby. Mrs. Dewitt was headed to the

Dewitt Patch when she discovered Burns’ body north of 17th Street

and west of Union. Donath is not sure of the exact location since

there is no scale on the sketch.

After the body was taken to the coroner’s office for an autopsy,

doctors discovered Burns was four months pregnant. Donath said the

coroner decided he better get a coroner’s jury going.

In the coroner’s office, Burns’ body was laid out for

identification. One young man who came in was what Donath said we

would call a “bus” driver at the railroad stations. The driver

recalled bringing Zura Burns to the Lincoln House that Saturday

morning.

Another person who came in to look at the body thought it looked

like the young woman who worked for the Carpenter family. The women

in the Carpenter family soon came down. Donath said they identified

her as Zura Burns.

The Investigation

Sheriff William Wendell, Coroner John T. Boyden, Dr. L.L. Leeds and

Dr. Katherine Miller were all involved in the investigation. The

coroner pulled together a jury of businessmen.

When Burns’ family was notified, Donath said the father came up from

St. Elmo to Lincoln. Zura’s brother and sister soon arrived too.

They all came to attend the hearings.

The coroner pulled a jury together. Donath said over 60 people were

interviewed. Those involved in the investigation pulled in anyone

with possible information on the crime.

Though all the evidence was circumstantial and did not point to

anyone, Donath said Orin Carpenter’s name came up more often during

interviews.

However, Orin Carpenter was not the only suspect. Other suspects

included Burns’ fiancé Thomas Dukes and Dow Cubbage, who Burns had

been sending letters to. The bus driver was another suspect.

Also on the suspect list was depot newspaper seller Burt Carter from

Decatur. Carter spent quite a bit of time with Zura Burns. Burns

often stayed with a woman in Decatur who apparently was a madame.

The investigation lasted from October 17th until November 1st.

through the inquest. At the end of the inquest, Donath said the

jurors had a verdict. They determined some sharp instrument had

caused Burns’ death.

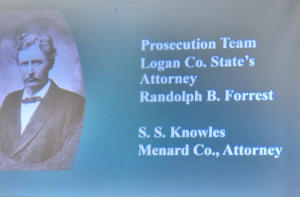

States’ Attorney Randolph Forrest was out of town when the incident

happened and was not yet back when they needed a prosecutor. Donath

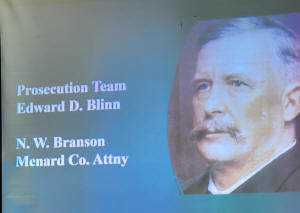

E.D. Blinn stepped into the role until Forrest could return.

Donath said there was a lot of pressure on the

prosecution to get a murder conviction. There had been 38 murders

between 1839 (when the county was formed) and 1883. In all those

years, Donath said there had been only one conviction. The people of

Logan County were up in arms and wanted to see someone pay.

In August 1882, Donath said there had been a triple murder in Mt.

Pulaski of a farmer and two farmhands, who were all killed by having

their throats cut. This murder was solved in 1884 after Burns’

murder had happened.

The Inquest

Many people were involved in the inquest including

Justice of the Peace was Jacob T. Rudolph, Coroner Boyden, Sheriff

Wendell and State’s Attorney Forrest assisted by Edward Blinn.

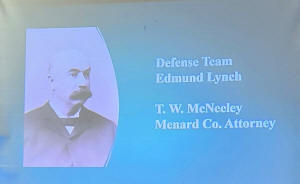

Timothy Beach and Joseph Hodnett were on the defense

team that represented Carpenter. Donath said they brought in Edmund

Lynch because he was a good speaker.

Dr. Leeds and Dr. Miller did the Post-Mortem and determined the

murder took place between midnight Sunday and 3 a.m. Monday, so

there was a short window of time. Unfortunately, Donath said

investigators could not place any suspects in the short window of

time the murder occurred.

Over 60 witnesses were interviewed. Donath said they came out of the

woodwork.

During the investigation, the county put up a $1000 reward for

information leading to an arrest. Others added in money, so Donath

said it made the reward around $1500.

Private detectives then started coming out of the woodwork. Donath

said most of them were not very good. Two of them used clairvoyants

to get their information.

Private Investigator Preston Butler, who was working

for the prosecution, searched Carpenter’s buggy and found some

hairpins in it. Donath said those hairpins may have belonged to his

mother, his wife, daughters or their friends who had ridden the

buggy.

Something else Donath said Butler found in the buggy was what

appeared to be a small bloodstain. After Butler showed the

bloodstain to Judge Rudolph, he said Carpenter needed to be

arrested. Carpenter was then arrested at his place of business.

Important Locations

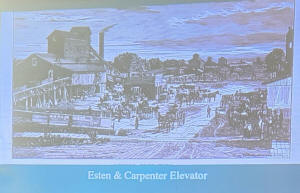

Carpenter was part owner of the Esten and Carpenter

Elevator near Chicago Street and Broadway Street. Donath said

Carpenter’s office played a critical role in the investigation.

Because Carpenter was buying out Martiline’s Elevator in Hartsburg,

Donath said Carpenter worked many late nights in the office. The

weekend of the murder Carpenter was working late.

At the time the body was found on Monday, Carpenter was headed for

Hartsburg.

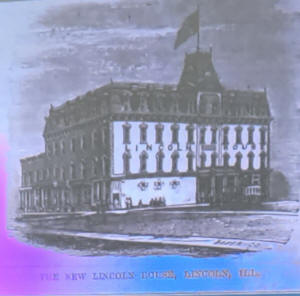

On the Saturday before the murder, Donath said Zura

Burns had gone to the office to see Carpenter and talk to him about

where her sister was. Carpenter was to pay Burns for work she had

done. After talking to Carpenter, Burns went to the New Lincoln

House nearby.

[to top of second column] |

When the whip, hairpins and rings

were tested for bloodstains by specialists in Chicago, Donath

said the results were inconclusive.

At that point, Donath said nobody had

been bound over to the grand jury to be the prime suspect for the

murder. Carpenter was in jail, and they had already had the

coroner’s jury.

There was a preliminary hearing for the grand jury, which Donath

said was presided over by Judge Lyman Lacey of Mason City. The same

60 witnesses were called, and the evidence was still circumstantial,

but Lacey wanted the grand jury to look at everything. Lacey then

bound Carpenter over to the grand jury, which would be in January

1884.

The Grand Jury

As the grand jury convened, Donath said news of the activity was

very secret. No one was let into the jury room and very little was

in the papers. However, the grand jury returned with a five-count

indictment against Carpenter.

The defense team knew Carpenter would not get a fair trial in Logan

County. Donath said they changed the venue to Menard County due to

the safety of the jurors and others in Logan County. In March 1884,

the trial convened in Petersburg.

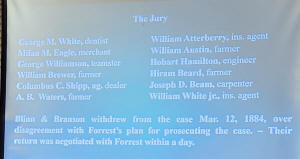

Several court officers were involved in helping

negotiate through the system. Donath said they included Judge Lacey,

State’s Attorney Forrest and Menard County Attorney S. S. Woodward.

On the prosecution team were attorneys Edward D. Blinn of Logan

County and N.W. Bronson of Menard County.

Donath said the defense team was made up of Timothy

T. Beach, Joseph Hodnett, Edmund Lynch and Menard County’s T.W.

McNeely.

The defense lawyers asked potential jurors if they

would convict based on circumstantial evidence. They interviewed 88

jurors in order to choose 12. The jurors chosen said they would not

convict on circumstantial evidence.

In this trial, Donath said the testimony was identical to the

testimony in other hearings. Nothing new had developed in that time

and nothing else was found that would bring other suspects in. He

said everyone [thought they] knew the verdict before the trial

started. Reporters said only one conclusion could come out of it.

There were two weeks of testimony by more than 100 witnesses.

Forrest spoke for four or five hours in both opening and closing.

Donath said he loved to hear himself talk.

After long overnight deliberations, Donath said the first vote was

7-5 for acquittal. Jurors kept discussing the case and the next vote

was 10-2. Donath said by 3 a.m., the final vote was unanimous for

the acquittal of Orin Carpenter.

The judge opened court, read the not guilty verdict

and dismissed the jury.

Donath said that would usually be the end of everything, but the

judge ran into the court of public opinion. A notice of a mass

meeting at the courthouse was posted in all the papers in Lincoln.

The newspapers said thousands showed up. In the old courthouse,

Donath said only 200 could get in.

A committee of seven was selected to write some resolutions against

Carpenter. Donath said there were also speeches by Carpenter’s

minister and by Mr. Burns, who was a heavy drinker and unstable.

These men publicly condemned Carpenter.

Several resolutions were adopted, and one resolution said Carpenter

must leave the county without delay. Donath said a committee of 50

was selected to deliver the resolutions to Carpenter.

This committee walked down Broadway, up Union and down Ninth Street,

to Carpenter’s house. They selected one man to hand deliver the

resolutions to Carpenter, who met him on the porch. The man read the

resolutions to Carpenter, but Donath said Carpenter told the man “I

do not recognize your authority in this matter. Because Carpenter

would not accept the resolutions, the man laid them on the porch and

left.

Though the group had agreed there would be no violence, Donath said

the sheriff had contacted the state because there had been talk

about lynching Carpenter. The militia was available if needed.

Carpenter refused to leave because he wanted to make his own

decision. However, Donath said one resolution stated if Carpenter

stayed, they would make sure no farmer in the county would bring

grain to Carpenter’s elevator anymore.

Since losing so much business would have also ruined his good friend

and partner Esten, Carpenter decided to sell off all his properties

and leave. Donath said Carpenter and his family then moved to Blunt,

Dakota where they had good friends. The Carpenter family later moved

to Sioux Falls, where they had a farm.

In December 1884, Carpenter came back to Lincoln to finish up some

business. Donath said Mr. Burns had heard Carpenter was in town.

Burns shot at Carpenter while Carpenter met with Uriah Hill. The

shot hit the iron façade of the building and bounced off.

When Burns ran down the street claiming he had killed Carpenter,

Donath said the police did not try to catch Burns.

After 1884, Carpenter did not return to Lincoln for 25 years.

Even Donath is unsure of whether Carpenter was truly guilty.

The case became famous all around the United States from the

Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. Donath said the Decatur Herald

Review had great coverage of the trial and did not leave out

details. He was disappointed in the papers who covered the trial in

Petersburg because so many details were left out.

Over the years, Donath said four publications about the case have

come out. One is a “lurid novel” by Charles James titled Zura Burns,

or the Fatal Step. Another is a case study by Beverly Smith titled

The Murder of Zura Burns, 1883: A Case Study of a Homicide in

Lincoln.

There is also a novel by William Krueger titled

Between Moonlight Murder: The Girl in Blind Lane. Finally, there is

a 2015 blog post by Robert Wilhelm called the Mystery of Zora Burns,

in Murder by Gaslight. Donath said the blog appears to have

inaccurate information. Donath said Wilhelm’s sources were from

newspapers back East.

Once Donath finished his presentation there were several questions.

LCGHS member Ellen Dobihal asked if the train depot

was near Carpenter’s grain elevator and Donath said yes.

The question LCGHS member Curt Fox had was whether the murder weapon

was found.

Donath said not only was the murder weapon not found, but none of

the items Burns had with her were ever found.

From Donath’s perspective, there was a lack of blood evidence on

Carpenter or in the buggy. He said the tracks near the body

apparently did not match Carpenter’s buggy tracks. Donath felt even

the timing of the murder did not fit.

As for who killed Zura Burns, some members thought it may have been

her fiancé, the minister or the father of the baby.

Sadly, we may never know exactly what happened that night or whether

Orin Carpenter killed Zura Burns.

The annual Logan County and Genealogical Historical Society dinner

and meeting will be held Monday, November 20 at Daphnes’ Restaurant

at 6:30 p.m. Those attending will hear a presentation about the

Atlanta, Illinois Giants Museum.

For those wanting to attend the dinner, reservation forms can be

picked up at the LCGHS building and must be turned in by November

10.

[Angela Reiners]

|