Dinosaur-killing asteroid impact fouled Earth's atmosphere with dust

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 31, 2023]

By Will Dunham [October 31, 2023]

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - It was, to put it mildly, a bad day on Earth when

an asteroid smacked Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula 66 million years ago,

causing a global calamity that erased three-quarters of the world's

species and ended the age of dinosaurs.

The immediate effects included wildfires, quakes, a massive shockwave in

the air and huge standing waves in the seas. But the coup de grâce for

many species may have been the climate catastrophe that unfolded in the

following years as the skies were darkened by clouds of debris and

temperatures plunged.

Researchers on Monday revealed the potent role that dust from pulverized

rock ejected into the atmosphere from the impact site may have played in

driving extinctions, choking the atmosphere and blocking plants from

harnessing sunlight for life-sustaining energy in a process called

photosynthesis.

The total amount of dust, they calculated, was about 2,000 gigatonnes -

exceeding 11 times the weight of Mt. Everest.

The researchers ran paleoclimate simulations based on sediment unearthed

at a North Dakota paleontological site called Tanis that preserved

evidence of the post-impact conditions, including the prodigious dust

fallout.

The simulations showed this fine-grained dust could have blocked

photosynthesis for up to two years by rendering the atmosphere opaque to

sunlight and remained in the atmosphere for 15 years, said planetary

scientist Cem Berk Senel of the Royal Observatory of Belgium and Vrije

Universiteit Brussel, lead author of the study published in the journal

Nature Geoscience.

While prior research highlighted two other factors - sulfur released

after the impact and soot from the wildfires - this study indicated dust

played a larger role than previously known.

The dust - silicate particles measuring about 0.8-8.0 micrometers - that

formed a global cloud layer were spawned from the granite and gneiss

rock pulverized in the violent impact that gouged the Yucatan's

Chicxulub (pronounced CHIK-shu-loob) crater, 112 miles (180 km) wide and

12 miles (20 km) deep.

In the aftermath, Earth experienced a drop in surface temperatures of

about 27 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius).

"It was cold and dark for years," Vrije Universiteit Brussel planetary

scientist and study co-author Philippe Claeys said.

[to top of second column]

|

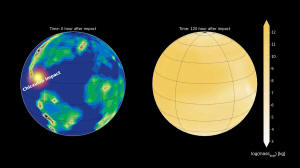

This illustration depicts paleoclimate model simulations that show

the rapid dust transport across Earth, indicating that the world was

encircled by the silicate dust ejecta within a few days following

the impact of an asteroid off Mexico's coast 66 million years ago in

this undated handout. Cem Berk Senel/Handout via REUTERS

Earth descended into an "impact winter," with global temperatures

plummeting and primary productivity - the process land and aquatic

plants and other organisms use to make food from inorganic sources -

collapsing, causing a chain reaction of extinctions. As plants died,

herbivores starved. Carnivores were left without prey and perished.

In marine realms, the demise of tiny phytoplankton caused food webs

to crash.

"While the sulfur stayed about eight to nine years, soot and

silicate dust resided in the atmosphere for about 15 years after the

impact. The complete recovery from the impact winter took even

longer, with pre-impact temperature conditions returning only after

about 20 years," Royal Observatory of Belgium planetary scientist

and study co-author Özgür Karatekin said.

The asteroid, estimated at 6-9 miles (10-15 km) wide, brought a

cataclysmic end to the Cretaceous Period.

The dinosaurs, aside from their bird descendants, were lost, as were

the marine reptiles that dominated the seas and many other groups.

The big beneficiary were the mammals, who until then were bit

players in the drama of life but were given the opportunity to

become the main characters.

"Biotic groups that were not adapted to survive dark, cold and

food-deprived conditions for almost two years would have experienced

massive extinctions," Karatekin said. "Fauna and flora that could

enter a dormant phase - for example, through seeds, cysts or

hibernation in burrows - and were able to adapt to a generalistic

lifestyle - not dependent on one particular food source - generally

survived better, like small mammals."

Absent this disaster, dinosaurs might still dominate today.

"Dinos dominated Earth and were doing just fine when the meteorite

hit," Claeys said. "Without the impact, my guess is that mammals -

including us - had little chance to become the dominant organisms on

this planet."

(Reporting by Will Dunham, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien)

[© 2023 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]This material

may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|