Why the US offshore wind industry is in the doldrums

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[September 07, 2023]

By Scott DiSavino and Nerijus Adomaitis [September 07, 2023]

By Scott DiSavino and Nerijus Adomaitis

(Reuters) - The value of Danish energy company Orsted, the world's

largest offshore wind farm developer and a big player in the U.S., has

plunged about 31% since it declared $2.3 billion in U.S. impairments in

late August due to supply delays, high interest rates and a lack of new

tax credits.

The company is just one of several energy firms trying to build new

offshore wind farms in the U.S., but the pain it is feeling is rippling

across the entire industry, raising questions about the future of fleet

of projects that U.S. President Joe Biden hopes can help fight climate

change.

Bidenís administration wants the U.S. to deploy 30,000 megawatts (MW) of

offshore wind by 2030 from a mere 41 MW now, a key part of his plan to

decarbonize the power sector and revitalize domestic manufacturing, and

has passed lucrative subsidies aimed at helping companies do that.

But even with regulatory rules and subsidies in place, developers are

facing a whole new set of headwinds.

Here is what they are:

INFLATION

The U.S. offshore wind industry has developed much more slowly than in

Europe because it took years for the states and federal government to

provide subsidies and draw up rules and regulations governing the

industry, slowing leasing and permitting.

However, as government policies started to line up in the industry's

favor in recent years, offshore wind developers unveiled a host of new

project proposals, mostly off the U.S. East Coast. Two small projects

came into operation - Orsted's five-turbine Block Island wind farm off

Rhode Island and the first two test turbines of U.S. energy firm

Dominion Energy's Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind off Virginia. Then came

a hitch.

The COVID-19 pandemic gummed up supply chains and increased the cost of

equipment and labor, making new projects far more expensive than

initially projected.

"It appears the offshore wind industry bid aggressively for early

projects to gain a foothold in a promising new industry, anticipating

steep (cost) declines similar to those for onshore wind, solar and

batteries over the past decade," Eli Rubin, senior energy analyst at

energy consulting firm EBW Analytics Group, told Reuters.

"Instead, steep cost gains threw project financing and development into

disarray," Rubin said, noting many contracts will likely be renegotiated

as states look to decarbonize, with higher prices ultimately falling

onto power customers.

INTEREST RATES

Financing costs also spiraled as the U.S. Federal Reserve boosted

interest rates to tame inflation.

[to top of second column]

|

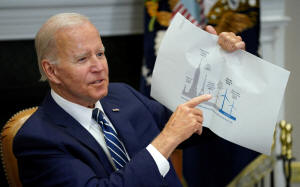

U.S. President Joe Biden holds up a wind

turbine size comparison chart while attending a meeting with

governors, labor leaders, and private companies launching the

Federal-State Offshore Wind Implementation Partnership, at the White

House in Washington, U.S., June 23, 2022. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque/File

Photo

Many contracts for offshore wind projects have no mechanism for

adjustment in the case of higher interest rates or costs.

Some developers have paid to get out of their contracts rather than

build them and face years of losses or low returns.

In Massachusetts, two offshore wind developers, SouthCoast Wind and

Commonwealth Wind, for example, agreed to pay to terminate deals

that would have delivered around 2,400 MW of energy, enough to power

over one million homes.

In New York, offshore wind developers also sought to boost the price

of power produced at their projects. Norway's Equinor and its

partner BP are seeking a 54% increase for the power produced at

three planned offshore wind farms - Empire Wind 1 and 2 and Beacon

Wind.

Orsted, meanwhile, told utility regulators in June that it would not

be able to make a planned final investment decision to build its

proposed 924-MW Sunrise Wind project unless its power purchase

agreement was amended to factor in inflation.

INSUFFICIENT SUBSIDIES

Bidenís administration has sought to supercharge clean energy

development with passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), a

sweeping law that provides billions of dollars of incentives to

projects that fight climate change.

Since the law passed last year, companies have announced billions of

dollars in new manufacturing for solar and electric vehicle (EV)

batteries across the U.S.

But the offshore wind industry is not fully satisfied.

Bonus incentives for using domestic materials and for siting

projects in disadvantaged communities are too hard to secure,

developers say, and they are crucial to making projects work in a

high-cost environment.

The credits are each worth 10% of a project's cost and can be

claimed as bonuses on top of the IRA's base 30% credit for renewable

energy projects - bringing a project's total subsidy to as much as

50%.

Equinor, France's Engie, Portugal's EDP Renewables, and trade groups

representing other developers pursuing offshore wind projects in the

U.S. told Reuters they are pressing officials to rewrite the

requirements, and warning of lost jobs and investments otherwise.

(Reporting by Scott DiSavino in New York, Nerijus Adomaitis in Oslo

and Nichola Groom in Culver City; Editing by Simon Webb and

Marguerita Choy)

[© 2023 Thomson Reuters. All rights

reserved.]This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|