|

Before

sharing his presentation, Keller gave an update on the museum. When

Lincoln College closed in May 2022, Keller said the board of

trustees committed themselves to keeping the museum open. He said

they know the museum is very crucial to the Lincoln scholarship

world, the community, and the economy of the community. Before

sharing his presentation, Keller gave an update on the museum. When

Lincoln College closed in May 2022, Keller said the board of

trustees committed themselves to keeping the museum open. He said

they know the museum is very crucial to the Lincoln scholarship

world, the community, and the economy of the community.

The museum is also important to national and international visitors.

Every week, Keller said people from all over the world come to visit

the Lincoln Heritage Museum. Just last week, he said there were

visitors from the Netherlands, England, Australia, New Zealand,

Germany and Spain. People from around 20 to 30 states visit too and

Keller said they would not be stopping in Lincoln if it were not for

the museum.

Keller is proud of what the museum has been and where it will go in

the future. The college is funding the museum and Keller’s salary.

He is hoping the museum will be able to stay open as long as

possible.

Next, Keller discussed some items in the museum

collection connected to Logan County. The collection is

predominantly Abraham Lincoln related and there are a lot of unique

Abraham Lincoln items.

What Keller wanted to focus on for his presentation was the Logan

County history in the museum. Many were items Keller said some

people may not know about.

If there was something that piqued people’s interest and they wanted

to research it, Keller said to let him know. The vault in the museum

is always open for people to come in and do research. The museum is

a “laboratory” for people to learn more about history.

Among the many items in the museum Keller marvels,

there are also “puzzles” or mysteries he wants to uncover. He is

looking for people to fill in missing gaps in information needed and

would love to have more volunteers.

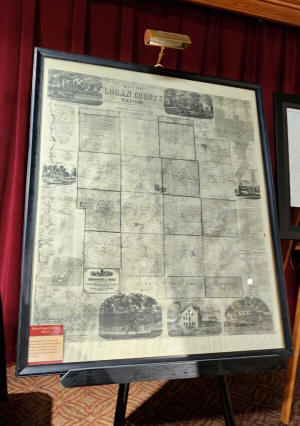

The “show and tell” Keller did included a large map

of Logan County from 1863 or 1864 during the Civil War. It has the

business directory of Lincoln including some elected officials, so

Keller went through Logan County records to find out who was in

office at these periods. The map lists the towns and the plats of

the town at the time. One person said LCGHS has a copy of this map.

When Sally Turner was Logan County Clerk and Recorder, Keller said

she gave the museum some old county records. These records had been

stored in the basement of the courthouse and Turner felt

uncomfortable having these items stuffed in boxes in a damp,

non-climate-controlled area.

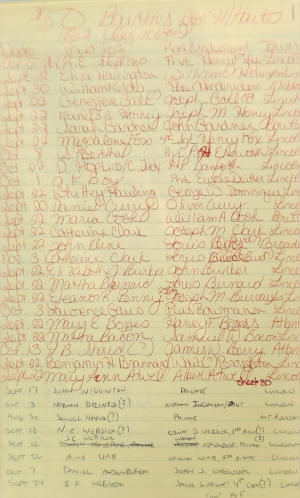

In the years since the museum got the records, Keller

said they have been catalogued. The records go all the way back to

1863 and include pay stubs and records for Logan County soldiers

with lists of their names, dates and pay rates. If anyone wants to

look up ancestors, Keller said they find their names in these

records.

Other records included stray records of lost cattle, horses and

sheep from 1870 to the 1890s. Keller said when a student did some

research on stray records, the student wondered why so many animals

were lost. Since people did not have vehicles, these animals were

their mainstays. Keller said some people had to sue to get their

animals back.

Polling and election records from the 1870s to 1890s

are another collection the museum received. Keller said there are

names attached to these records.

All the records are in hard copy and saved on a floppy disk.

Unfortunately, Keller does not have a way to open a floppy disk.

Keller hopes to enter them into digital records at some point.

One large document given to the museum by Joe and

Sudle Mintjal is a Civil War Muster Roll for the 106th Illinois

Infantry Company F for the period from February 28 to April 30,1863.

This regiment fought in many battles including the Battle of

Vicksburg. They were mustered out of service in July 1865 and

discharged from Camp Butler, Illinois on July 24, 1865.

The oldest item Keller said the museum has is an 1822 ferry license

for Erastus Wright to operate his ferry in Peoria. Wright was a

Logan County resident and Keller believes he was the first teacher

in the county.

One LCGHS member said Wright moved here from Connecticut in 1821. He

taught on Elkhart Hill.

Road petitions from Salt Creek and other places provide a history of

the first roads built in the county. Keller said one 1824 road

petition relates to a road from Lincoln to Elkhart,

Keller said there are six boxes of an Ed Madigan

collection. Madigan grew up in Lincoln and graduated from Lincoln

Junior College before he started his own taxicab business.

Madigan served as a member of the Lincoln Board of Zoning Appeals

from 1965 to 1969 and was elected to the Illinois House of

Representatives in 1967, serving in that role until 1973. He was

elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1972 and served nine

terms. From 1991 to 1993, Madigan served as Secretary of

Agriculture.

There are plaques, awards, photos, and other items in the Ed Madigan

collection. Keller said no one here has done research on Madigan, so

if anyone is looking for information on him, he could help.

Several records in the museum include Civil War letters. Keller said

there are many letters from Joseph Ross, a medical surgeon who

served during the Civil War. Following the Civil War, Ross moved to

Logan County. In 1866, Ross helped organize Lincoln’s First

Presbyterian Church and the county’s first Medical Society. In 1869,

Ross was elected as a city alderman, serving several terms. He was

later elected to the Illinois House of State Representatives.

Though Keller has never been able to find a photograph of Ross, he

has contacted Illinois State Archivist Dave Jones. Jones thinks he

may have a photo of Ross. Keller said Ross may go from mystery to

marvel if he gets a photograph.

Through reading a book about medical surgeons, Keller

discovered surgeons were the least likely to write letters because

of the horrific and graphic things they dealt with. In addition,

they were often too busy to write letters. Keller is fascinated by

Ross’s letters, which do not talk about the weather or the battles

or provide news from the front like many soldier’s letters do.

[to top of second column] |

Some of Ross’s letters were read aloud by Keller. In

these letters Ross chides his wife for not writing him often enough.

For example, in one letter, Ross says “you say you have written

seven times and I have received only five [letters].” Ross listed

the dates he had written his wife and told her he would be better

pleased if she would write “oftener.”

In another letter, Ross said some in his unit got letters every

week. A letter Ross started with “my dear little wife” told her he

envied her getting three or four letters a week from him. Meanwhile,

Ross said he had to wait a whole month to get a letter from her.

Ross tells his wife he is not scolding her but is begging her and

entreating her to write “oftener.”

Because Ross was a medical surgeon during the war, he saw some

horrible wounds. Keller finds the detail Ross went into a December

11, 1863, letter from Prairie Grove, Arkansas interesting.

In the letter, Ross said he does not like to see

people butchered up, but when it is necessary to cut, he would

rather do it than not. Ross does not want to give a long description

of the horrid nature of wounds he has seen so as not to shock her

sensibilities. However, Ross said he had seen wounds of every

conceivable nature: legs shot off, faces shot off and bodies

disemboweled. Ross had seen more dead than he had ever seen in his

life.

A July 4,1863, letter Ross wrote about the Battle of Vicksburg

showed he understood how important the battle was. Ross said his

heart was full and he could scarcely talk about anything else. He

felt it was one of the greatest fourth of July’s in the country and

felt confident about his side’s victory.

After seeing the first regiment of “colored” troops

he had ever seen in Memphis, Ross wrote to his wife that it looked

odd but great to see their black faces peeking out in federal

uniform. Ross said they presented a fine appearance and looked like

real soldiers.

The site of those fellows armed for their families and country was

evidence to Ross that “God is on our side.” In his letter dated June

11, 1863, Ross said these people still needed justice done to them

in full. They had yet to be recognized and treated as human beings

and brothers possessing the rights to personal and political

freedom.

From reading the view Ross expressed in this letter, Keller found

Ross to be very equalitarian. Ross viewed racism and slavery as an

ugly sin the nation was guilty of, feeling the nation was suffering

the punishments and vengeance of heaven as a result.

Because Keller is still researching Joseph Ross’s life, he is not

sure if he practiced medicine in the county as someone asked.

Someone else pointed out that since Ross started a medical society

here, it seems likely he did practice medicine in the county.

Abraham Lincoln owned a “lot” of land on the square until the day he

died. Keller said Lincoln acquired the land from Primm. After

Lincoln died, the land was bequeathed to his family. Keller said the

Logan County Treasurer John Jenkins received a letter from Judge

David Davis asking that the taxes on the lot be removed on behalf of

Lincoln’s family.

Davis was a Supreme Court Justice by that time, so Keller said he

had a lot of pull. Jenkins wrote Judge Davis back and said the taxes

would be forgiven and the Lincoln family had nothing to worry about.

A funeral train schedule for Abraham Lincoln is

another part of the museum collection. This schedule lists all the

places where the funeral train stopped including Atlanta, Lincoln,

and other places in the area.

Several years ago, Lincoln College graduate David Shroyer gave the

college glass negatives from local photographer Walter Tandy. Tandy

was a photographer in the area from the 1870s to the early part of

the 20th century. Some of the glass negatives are also at Lincoln

Public Library.

Former Lincoln College student David Doolin has scanned all 130

glass negatives.

About one third of the negatives have been developed and blown up.

Keller said he and others have been able to identify who or what is

in some of them.

The fifteen photos Keller showed everyone included

ones of the old Adams School, Jefferson School, Madison School, and

the three sister’s houses. Other photos show Elkhart Bridge and the

old power plant south of town.

Photos of people included local teacher Herbert Merry, an

unidentified African American man, a man and boy, and several

children. One has people in a horse drawn wagon with Lincoln

College’s University Hall in the background.

A photo album Keller bought online has photos of the first Lincoln

College President Anzo Freeman taken at Albert’s Studio. The album

also contains photos of many other people and the Lizzie Freeman

house. Keller would like to find out where that house is.

When someone asked Keller about the album, he said he bought the

album because it had once belonged to Freeman.

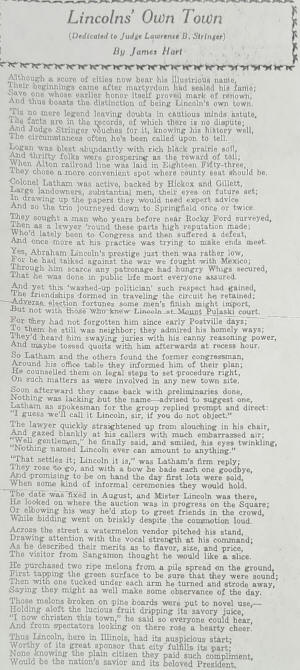

Writings in the museum collection now include two

poems by James Hart, a student or protégé of Judge Lawrence

Stringer. Keller handed out copies of these long poems. One is

titled “Lincoln’s Last Journey” and talks about Lincoln’s body

travelling to its burial site in Springfield. The other one is

“Lincoln’s Own Town,” which Keller said is about Lincoln, Illinois.

Most of the items Keller said the museum has are from Abraham

Lincoln and the Civil War era. To find out more about the history of

the county, Keller said people should visit the Logan County

Genealogical Society building on North Chicago Street. As Keller

said, both the museum and the historical society have a story to

tell.

The Lincoln Heritage Museum hours are Tuesdays through Fridays from

9-4 and Saturdays from 1 to 4. Keller said admission is one dollar.

After Keller’s presentation, he left several items

out for people to look at more closely.

The next Logan County Genealogical and Historical Society meeting

will be Monday, October 18 at 6:30 p.m. at their building at 114 N.

Chicago Street. LCGHS president Bill Donath will be on the 1883 Zora

Burns murder, which happened in Lincoln.

[Angela Reiners]

|