Terry Anderson, US journalist held hostage nearly 7 years in Lebanon,

dead at 76

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[April 22, 2024]

By Alistair Bell [April 22, 2024]

By Alistair Bell

(Reuters) -Terry Anderson, a U.S. journalist who was held captive by

Islamist militants for almost seven years in Lebanon and came to

symbolize the plight of Western hostages during the country's 1975-1990

civil war, died on Sunday at age 76, his daughter said in a statement.

The former chief Middle East correspondent for The Associated Press, who

was the longest held hostage of the scores of Westerners abducted in

Lebanon, died at his home in Greenwood Lake, New York, said his daughter

Sulome Anderson, who was born three months after he was seized. No cause

of death was given.

Kept in barely-lit cells by mostly Shi'ite Muslim groups in what was

known as The Hostage Crisis, and chained by his hands and feet and

blindfolded much of the time, the former Marine later recalled that he

"almost went insane" and that only his Roman Catholic faith prevented

him from taking his life before he was freed in December 1991.

"Though my father's life was marked by extreme suffering during his time

as a hostage in captivity, he found a quiet, comfortable peace in recent

years. I know he would choose to be remembered not by his very worst

experience, but through his humanitarian work with the Vietnam

Children's Fund, the Committee to Protect Journalists, homeless veterans

and many other incredible causes," Sulome Anderson said.

The family will take some time to organize a memorial, she said.

Anderson's ordeal began in Beirut on the morning of March 16, 1985,

after he played a round of tennis. A green Mercedes sedan with curtains

over the rear window pulled up, three gunmen jumped out and dragged

Anderson, still dressed in shorts, into the car.

The pro-Iran Islamic Jihad group claimed responsibility for the

kidnapping, saying it was part of "continuing operations against

Americans." The abductors demanded freedom for Shi'ite Muslims jailed in

Kuwait for bomb attacks against the U.S. and French embassies there.

It was the start of a nightmare for Anderson that would last six years

and nine months during which he was stuck in cells under the

rubble-strewn streets of Beirut and elsewhere, often badly fed and

sleeping on a thin, dirty mattress on a concrete floor.

During captivity, both his father and brother would die of cancer and he

would not see his daughter Sulome until she was six years old.

"What kept me going?" he asked aloud shortly after release. "My

companions. I was lucky to have people with me most of the time. My

faith, stubbornness. You do what you have to. You wake up every day,

summon up the energy from somewhere. You think you haven't got it and

you get through the day and you do it. Day after day after day."

Other hostages described Anderson as tough and active in captivity,

learning French and Arabic and exercising regularly.

However, they also told of him banging his head against a wall until he

bled in frustration at beatings, isolation, false hopes and the feeling

of being neglected by the outside world.

"There is a limit of how long we can last and some of us are approaching

the limit very badly," Anderson said in a videotape released by his

captors in December 1987.

Marcel Fontaine, a French diplomat who was released in May 1988 after

three years of captivity, recalled the time cell mate Anderson thought

freedom was near because he was allowed to see the sun and eat a

hamburger.

In April 1987 Anderson was given a suit of clothes that his captors had

made for him. "He wore it every day," Fontaine said.

A week later, however, Anderson's captors took the suit back, leaving

him in despair and certain he was forgotten, Fontaine said.

[to top of second column]

|

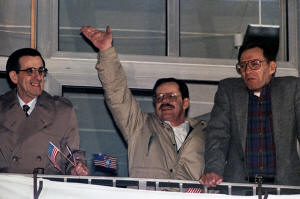

Hostages from the U.S. Joseph Cicippio,Terry Anderson and Alann

Steen which were held in Lebanon pose on the balcony of the U.S.

military hospital in Wiesbaden , Germany December 5, 1991 REUTERS/Reinhard

Krause

Scores of journalist groups, governments and individuals over the

years called for Anderson's release and his Oct. 27 birthday became

an unofficial U.S. memorial day for hostages.

Anderson said he considered killing himself several times but

rejected it. He relied heavily on his faith, which he said he had

renewed six months before being kidnapped.

"I must have read the Bible 50 times from start to finish," he said.

"It was an enormous help to me."

His sister, Peggy Say, who died in 2015, was his fiercest advocate

during captivity.

She worked tirelessly for her brother's freedom. She visited Arab

and European capitals, lobbied the Pope, the Archbishop of

Canterbury and every U.S. official and politician available.

Under pressure from the media and the U.S. hostages' families, the

Reagan administration negotiated a secret and illegal deal in the

mid-1980s to facilitate arms sales to Iran in return for the release

of American hostages. But the deal, known as the Iran–Contra affair,

failed to gain freedom for any of the hostages.

Born Oct. 27, 1947, in Lorain, Ohio, Anderson grew up in Batavia,

New York. He graduated from Iowa State University and spent six

years in the Marine Corps, mostly as a journalist.

He worked for the AP in Detroit, Louisville, New York, Tokyo,

Johannesburg and then Beirut, where he first went to cover the

Israeli invasion in 1982.

In that war-torn city, he fell in love with Lebanese woman Madeleine

Bassil, who was his fiance and pregnant with their daughter Sulome

when he was snatched.

He is survived by his daughters Sulome and Gabrielle, his sister

Judy and brother Jack, and by Bassil, whom Sulome Anderson called

"his ex-wife and best friend."

Anderson and fellow hostages developed a system of communication by

tapping on walls between their cells. Always the journalist,

Anderson passed on news of the outside world he had picked up during

captivity to Church of England envoy Terry Waite, being held hostage

in an adjacent room in September 1990 after years of solitary

confinement.

"Then the world news: the Berlin Wall's falling, communism's demise

in eastern Europe, free elections in the Soviet Union, work toward

multiracial government in South Africa. All the incredible things

that have happened since he was taken nearly three years ago. He

thought I was crazy," Anderson wrote in his 1993 book "Den of

Lions."

After his release, Anderson taught journalism at Columbia University

in New York, Ohio University, the University of Kentucky and the

University of Florida until he retired in 2015.

Among businesses he invested in were a horse ranch in Ohio, and a

restaurant. He unsuccessfully ran for the Ohio state Senate as a

Democrat in 2004 and sued Iran in federal court for his abduction,

winning a multimillion-dollar settlement in 2002.

(Reporting by Alistair Bell; Additional reporting by Daniel Trotta;

editing by Diane Craft)

[© 2024 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved.]This material

may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |