Biden adds to the nation's list of national monuments during his term.

There's an appetite for more

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[December 09, 2024]

By SUSAN MONTOYA BRYAN [December 09, 2024]

By SUSAN MONTOYA BRYAN

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) — U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt did in 1906

what Congress was unwilling to do through legislation: He used his new

authority under the Antiquities Act to designate Devils Tower in Wyoming

as the first national monument.

Then came Antiquities Act protections for the Petrified Forest in

Arizona, Chaco Canyon and the Gila Cliff Dwellings in New Mexico, the

Grand Canyon, Death Valley in California, and what are now Zion and

Bryce Canyon national parks in Utah.

The list goes on, as all but three presidents have used the act to

protect unique landscapes and cultural resources.

President Joe Biden has created six monuments and either restored,

enlarged or modified boundaries for a handful of others. Native American

tribes and conservation groups are pressing for more designations before

he leaves office.

The proposals range from an area dotted with palm trees and petroglyphs

in Southern California to a site sacred to Native Americans in Nevada's

high desert, a historic Black neighborhood in Oklahoma and a homestead

in Maine that belonged to the family of Frances Perkins, the nation’s

first female cabinet member.

Looting and destruction

Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act after a generation of lobbying by

educators and scientists who wanted to protect sites from commercial

artifact looting and haphazard collecting by individuals. It was the

first law in the U.S. to establish legal protections for cultural and

natural resources of historic or scientific interest on federal lands.

For Roosevelt and others, science was behind safeguarding Devils Tower.

Scientists have long theorized about how once-molten lava cooled and

formed the massive columns that make up the geologic wonder. Narratives

among Native American tribes, who still conduct ceremonies there, detail

its formation.

Biden cited the spiritual, cultural and prehistoric legacy of the Bears

Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante areas in southern Utah when he

restored their boundaries and protections through his first use of the

Antiquities Act in 2021.

The two monuments were among 29 that President Barack Obama created

while in office. Amid concerns that Obama overstepped his authority and

limited energy development, President Donald Trump rolled back their

size, while adding a previously unprotected portion to Bears Ears.

Biden called Bears Ears — the first national monument to be established

at the request of federally recognized tribes — a “place of healing.”

Saving sacred places

Early designations often pushed tribes from their ancestral homelands.

In one of his final acts as president in 1933, Herbert Hoover used the

Antiquities Act to set aside Death Valley as a national monument. It's

now one of the largest national parks — not to mention the hottest,

driest and lowest.

While establishing the monument brought an end to prospecting and the

filing of new mining claims in the area, it also meant the Timbisha

Shoshone were forced from the last bit of their traditional territory.

It took several decades for the tribe to regain a fraction of the land.

Biden's administration has made strides in working with some tribes on

managing public lands and incorporating more Indigenous knowledge into

planning and policymaking.

Avi Kwa Ame National Monument was Biden's second designation. The site

outside of Las Vegas is central to the creation stories of tribes with

ties to the area.

[to top of second column]

|

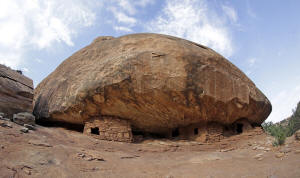

The "House on Fire" ruins in Mule Canyon, which is part of Bears

Ears National Monument, near Blanding, Utah, is seen June 22, 2016.

(AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File)

Republican Nevada Gov. Joe Lombardo

said at the time that the White House didn't consult his

administration before making the designation in 2023 — and in effect

blocked clean energy projects and other development in the state.

Similar opposition bubbled up when Biden designated

Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni National Monument in Arizona just months

later. This time it wasn't the prospect of clean energy projects

sprouting up across the desert, but rather uranium mining near the

Grand Canyon that had tribes and environmentalists pushing for

protections.

Creating conservation corridors

Biden certainly didn't break any records with the number of

monuments he designated or the amount of land set aside. But

conservationists say more strategic use of the authority under the

Antiquities Act will be valuable going forward as developers look to

build more solar and wind farms and mine for lithium and other

minerals required for a green energy transition.

They are pushing for Biden in his final weeks to expand California's

Joshua Tree National Park and establish a new monument that would

stretch from the Joshua Tree border to the Colorado River where it

divides California and Arizona. The proposed Chuckwalla National

Monument has the support of several tribes.

Such a designation would add a significant piece to one of the

largest contiguous protected corridors in the U.S. — spanning

thousands of square miles along the Colorado River from Canyonlands

in Utah, through the monuments already designated by Obama and Biden

to the desert oases of Southern California.

“The concern out there is that so much land is getting used for

renewable energy and it just kills the desert completely. And so if

we’re not more proactive about protecting these places in the

desert, we could lose them forever,” said Kristen Brengel, senior

vice president of government affairs for the National Parks

Conservation Association.

More than sweeping landscapes

Biden's designations have gone beyond the canyons and mesas of the

West.

In May, he designated a national monument at the site of the 1908

race riot in Springfield, Illinois. That designation came as he

tried to retain relevance in his final months in office and boost

Vice President Kamala Harris's presidential campaign while Trump cut

into Democrats' historic edge with Black voters.

In 2023, Biden created a national monument across three sites in

Illinois and Mississippi in honor of Emmett Till and his mother,

Mamie Till-Mobley. Emmett Till was the Black teenager from Chicago

who was abducted, tortured and killed in 1955 after he was accused

of whistling at a white woman in Mississippi.

A petition still is on the table for designating the Greenwood area

of North Tulsa, Oklahoma — the site of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

— as a national monument. So is a proposal to establish a monument

along the Maah Daah Hey Trail in the North Dakota Badlands, where

tribes want to shift the narrative to include stories about the

land's original inhabitants.

All contents © copyright 2024 Associated Press. All rights reserved |