Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson,

baseball's stolen base king, has died at 65

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[December 23, 2024]

By JOSH DUBOW [December 23, 2024]

By JOSH DUBOW

OAKLAND, Calif. (AP) — Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson, the brash

speedster who shattered stolen base records and redefined baseball's

leadoff position, has died. He was 65.

Henderson died on Friday. The Athletics said Saturday they were

“shocked and heartbroken by his passing," but did not specify a

cause of death.

Known as baseball's “Man of Steal,” Henderson had a lengthy list of

accolades and accomplishments over his nomadic 25-year career — an

MVP, 10 All-Star selections, two World Series titles and a Gold

Glove award.

“Rickey was simply the best player I ever played with. He could

change the outcome of a game in so many ways," said Don Mattingly,

Henderson's teammate with the New York Yankees from 1985-89. "It

puts a smile on my face just thinking about him. I will miss my

friend.”

It was stealing bases where Henderson made his name and dominated

the sport like no other.

He broke through with 100 steals in his first full season in the

majors in 1980, topping Ty Cobb's AL single-season record with Billy

Martin's “Billy Ball” Oakland Athletics. He barely slowed playing

for nine franchises over the next two decades. He broke Lou Brock's

single-season record of 118 by stealing 130 bases in 1982 and led

the league in steals for seven straight seasons and 12 overall.

Henderson surpassed Brock's career record when he stole his 939th

base on May 1, 1991, for Oakland, and famously pulled third base out

of the ground and showed it off to the adoring crowd before giving a

speech that he capped by saying: “Lou Brock was a great base

stealer, but today I am the greatest of all time.”

Henderson finished his career with 1,406 steals. His 468-steal edge

over Brock matches the margin between Brock and Jimmy Rollins, who

is in 46th place with 470.

“He’s the greatest leadoff hitter of all time, and I’m not sure

there’s a close second,” former A's executive Billy Beane said of

Henderson.

In September, Henderson insisted he would have had many more steals

in his career and in the record-breaking 1982 season if rules

introduced in 2023 to limit pickoff throws and increase the size of

bases had overlapped with his career.

“If I was playing today, I would get 162, right now, without a

doubt," he said. "Because if they had had that rule, you can only

throw over there twice, you know how many times they would be

throwing over there twice and they’d be going, ‘Ah, (shoot), can

y’all send him to third? Give him two bases and send him to third.’

That would be me.”

He even predicted how he could still be stealing more bases than the

current major leaguers even 20-plus years post-retirement: "If

they’re stealing 40-50 bases right now I’d lead the league.”

Henderson’s accomplishment that record-breaking day in 1991 was

slightly overshadowed that night when Nolan Ryan threw his record

seventh career no-hitter. Henderson already had been Ryan’s 5,000th

career strikeout victim, which led him to say, “If you haven’t been

struck out by Nolan Ryan, you’re nobody.”

That was clearly not the case for Henderson. He is also the career

leader in runs scored with 2,295 and in leadoff home runs with 81,

ranks second to Barry Bonds with 2,190 walks and is fourth in games

played (3,081) and plate appearances (13,346). He finished his

career with 3,055 hits over 25 seasons spent with Oakland, the

Yankees, Toronto, San Diego, Anaheim, the New York Mets, Seattle,

Boston and the Los Angeles Dodgers.

He fittingly finished his career with the Dodgers at age 44 in 2003

by scoring a run in his final play on a major league field.

Henderson is the third prominent baseball Hall of Famer with ties to

the Bay Area who died this year, following the deaths in June of

former Giants stars Willie Mays and Orlando Cepeda.

Henderson was the rare position player who hit from the right side

and threw with his left arm — but then again, everything about

Henderson was unique.

He batted out of an extreme crouch, making for a tighter strike zone

that contributed to his high walk total. He struck fear in opponents

with his aggressive leads off first, his fingers twitching between

his legs inside his batting gloves as he eyed the pitcher and the

next base.

[to top of second column] |

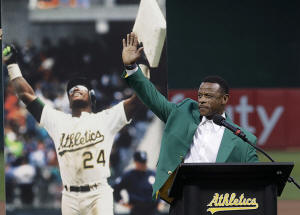

Former baseball player Rickey Henderson waves after speaking during

a ceremony inducting him into the Oakland Athletics' Hall of Fame

before a baseball game between the Athletics and the New York

Yankees in Oakland, Calif., Sept. 5, 2018. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu,

File)

Born on Christmas Day in 1958 in Chicago in the

back of his parents' Chevy, Henderson grew up in Oakland and

developed into a star athlete. He played baseball, basketball and

football at Oakland Tech High School and was a highly sought-after

football recruit who could have played tailback at Southern

California — where he likely would have eventually had the chance to

run alongside football Hall of Famer Marcus Allen.

But Henderson said his mother loved baseball and thought it would be

the safer career in a decision that proved to be prescient.

“She didn’t want her baby to get hurt,” Henderson told the San

Francisco Chronicle in 2019. “I was mad, but she was smart. Overall,

with the career longevity and the success I had, she made the right

decision. Some of the players in football now have short careers and

they can barely move around when they’re done.”

Henderson was selected in the fourth round of the 1976 amateur draft

by the hometown A's and made his big league debut in 1979 with two

hits — and, of course, one stolen base.

He became a star for the A's the following season and remained in

Oakland through 1984 before being traded to the Yankees. Henderson

was part of some talented teams in New York that never made the

postseason. In 1985, he scored 146 runs in 143 games to go along

with a league-leading 80 steals and 24 homers, helping start the

"80-20 club" that season with Cincinnati's Eric Davis.

Henderson was traded back to Oakland in June 1989, leading to his

greatest successes. He topped the AL that season with 113 runs, 126

walks and 77 steals, was named the ALCS MVP and helped lead the A's

to the World Series title in the earthquake-interrupted Bay Bridge

series by sweeping the Giants.

Henderson then won the AL MVP the following season for Oakland

before the A's lost the World Series to Cincinnati.

\ \

“I traded Rickey Henderson twice and brought him back more times

than that,” former A's general manager Sandy Alderson said. "He was

the best player I ever saw play. He did it all — hit, hit for power,

stole bases, and defended — and he did it with a flair that enthused

his fans and infuriated his opponents. But everyone was amused by

his personality, style, and third-person references to himself. He

was unique in many ways.

“Rickey stories are legion, legendary, and mostly true. But behind

his reputation as self-absorbed was a wonderful, kind human being

who loved kids. His true character became more evident over time.

Nine different teams, one unforgettable player.”

Henderson set the career steals record in 1991 and then was traded

two years later to Toronto, where he won his second World Series. He

spent the final decade of his career bouncing around the majors and

still led the AL with 66 steals and 118 walks at age 39 with Oakland

in 1998.

In 2017, the A's named their playing surface “Rickey Henderson

Field” at the Oakland Coliseum in his honor.

“When you’re old and grey, sitting around with your buds talking

about your career in baseball, you are going to talk about Rickey,"

said Ron Guidry, another of Henderson's former Yankees teammates.

"He was just amazing to watch. There were great outfielders. There

were great base stealers. There were great home run hitters. Rickey

was a combination of all of those players. He did things out there

on the field that the rest of us dreamed of.”

___

AP Baseball Writer Janie McCauley contributed to this report.

All contents © copyright 2024 Associated Press. All rights reserved

|