Earliest-known galaxy, spotted by Webb telescope, is a beacon to cosmic

dawn

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[June 01, 2024]

By Will Dunham [June 01, 2024]

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - NASA's James Webb Space Telescope has spotted the

earliest-known galaxy, one that is surprisingly bright and big

considering it formed during the universe's infancy - at only 2% its

current age.

Webb, which by peering across vast cosmic distances is looking way back

in time, observed the galaxy as it existed about 290 million years after

the Big Bang event that initiated the universe roughly 13.8 billion

years ago, the researchers said. This period spanning the universe's

first few hundred million years is called cosmic dawn.

The telescope, also called JWST, has revolutionized the understanding of

the early universe since becoming operational in 2022. The new discovery

was made by the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) research

team.

This galaxy, called JADES-GS-z14-0, measures about 1,700-light years

across. A light year is the distance light travels in a year, 5.9

trillion miles (9.5 trillion km). It has a mass equivalent to 500

million stars the size of our sun and was rapidly forming new stars,

about 20 every year.

Before Webb's observations, scientists did not know galaxies could exist

so early, and certainly not luminous ones like this.

"The early universe has surprise after surprise for us," said

astrophysicist Kevin Hainline of Steward Observatory at the University

of Arizona, one of the leaders of the study published online this week

ahead of formal peer review.

"I think everyone's jaws dropped," added astrophysicist and study

co-author Francesco D'Eugenio of the Kavli Institute for Cosmology at

the University of Cambridge. "Webb is showing that galaxies in the early

universe were much more luminous than we had anticipated."

Until now, the earliest-known galaxy dated to about 320 million years

after the Big Bang, as announced by the JADES team last year.

"It makes sense to call the galaxy big, because it's significantly

larger than other galaxies that the JADES team has measured at these

distances, and it's going to be challenging to understand just how

something this large could form in only a few hundred million years,"

Hainline said.

"The fact that it's so bright is also fascinating, given that galaxies

tend to grow larger as the universe evolves, implying that it would

potentially get significantly brighter in the next many hundred million

years," Hainline said.

[to top of second column]

|

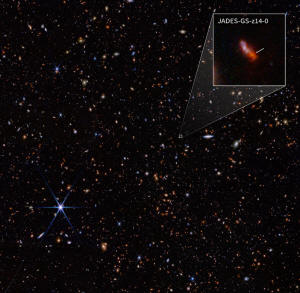

An infrared image from NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, taken by

the NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) for the JWST Advanced Deep

Extragalactic Survey, or JADES, program. One such galaxy,

JADES-GS-z14-0 (shown in the pullout), was determined to have formed

about 290 million years after the Big Bang, making it the

earliest-known galaxy. NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Brant Robertson (UC

Santa Cruz), Ben Johnson (CfA), Sandro Tacchella (Cambridge), Phill

Cargile (CfA)/Handout via REUTERS/File Photo

While it is quite big for such an early galaxy, it is dwarfed by

some present-day galaxies. Our Milky Way is about 100,000 light

years across, with the mass equivalent to about 10 billion sun-sized

star.

The JADES team in the same study disclosed the discovery of the

second oldest-known galaxy, from about 303 million years post-Big

Bang. That one, JADES-GS-z14-1, is smaller - with a mass equal to

about 100 million sun-sized stars, measuring roughly 1,000 light

years across and forming about two new stars per year.

"These galaxies formed in an environment that was much more dense

and gas-rich than today. In addition, the chemical composition of

the gas was very different, much closer to the pristine composition

inherited from the Big Bang - hydrogen, helium and traces of

lithium," D'Eugenio said.

Star formation in the early universe was much more violent than

today, with massive hot stars forming and dying quickly, and

releasing tremendous amount of energy through ultraviolet light,

stellar winds and supernova explosions, D'Eugenio said.

Three main hypotheses have been advanced to explain the luminosity

of early galaxies. The first attributed it to supermassive black

holes in these galaxies gobbling up material. That appears to have

been ruled out by the new findings because the light observed is

spread over an area wider than would be expected from black hole

gluttony.

It remains to be seen whether the other hypotheses - that these

galaxies are populated by more stars than expected or by stars that

are brighter than those around today - will hold up, D'Eugenio said.

(Reporting by Will Dunham; Editing by Daniel Wallis)

[© 2024 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved.]This material

may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |