“No Schoolers”: How Illinois’ hands-off approach to homeschooling leaves

children at risk

At 9 years old, L.J. started missing school.

His parents said they would homeschool him. It took two years — during

which he was beaten and denied food — for anyone to notice he wasn’t

learning.

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[June 06, 2024]

By BETH HUNDSDORFER

& MOLLY PARKER

CAPITOL NEWS ILLINOIS

investigations@capitolnewsillinois.com

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local

Reporting Network in partnership with Capitol News Illinois. This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local

Reporting Network in partnership with Capitol News Illinois.

It was on L.J.’s 11th birthday, in December 2022, that child welfare

workers finally took him away. They arrived at his central Illinois home

to investigate an abuse allegation and decided on the spot to remove the

boy along with his baby brother and sister — the “Irish twins,” as their

parents called them.

His mother begged to keep the children while her boyfriend told child

welfare workers and the police called to the scene that they could take

L.J.: “You wanna take someone? Take that little motherfucker down there

or wherever the fuck he is at. I’ve been trying to get him out of here

for a long time.”

By that time, L.J. told authorities he hadn’t been in a classroom for

years, according to police records. First came COVID-19. Then, in August

2021 when he was going to have to repeat the third grade, his mother and

her boyfriend decided that L.J. would be homeschooled and that they

would be his teachers. In an instant, his world shrank to the confines

of a one-bedroom apartment in the small Illinois college town of

Charleston — no teachers, counselors or classmates.

In that apartment, L.J. would later tell police, he was beaten and

denied food: Getting leftovers from the refrigerator was punishable by a

whipping with a belt; sass was met with a slap in the face.

L.J. told police he got no lessons or schoolwork at home. Asked if he

had learned much, L.J. replied, “Not really.”

Reporters are using the first and middle initials of the boy, who is now

12 and remains in state custody, to protect his identity.

While each state has different regulations for homeschooling — and most

of them are relatively weak — Illinois is among a small minority that

places virtually no rules on parents who homeschool their children: The

parents aren’t required to register with any governmental agency, and no

tests are required. Under Illinois law, they must provide an education

equivalent to what is offered in public schools, covering core subjects

like math, language arts, science and health. But parents don’t have to

have a high school diploma or GED, and state authorities cannot compel

them to demonstrate their teaching methods or prove attendance,

curriculum or testing outcomes.

The Illinois State Board of Education said in a statement that regional

education offices are empowered by Illinois law to request evidence that

a family that homeschools is providing an adequate course of

instruction. But, the spokesperson said, their “ability to intervene can

be limited.”

Educational officials say this lack of regulation allows parents to pull

vulnerable children like L.J. from public schools then not provide any

education for them. They call them “no schoolers.”

No oversight also means children schooled at home lose the protections

schools provide, including teachers, counselors, coaches and bus drivers

— school personnel legally bound to report suspected child abuse and

neglect. Under Illinois law, parents may homeschool even if they would

be disqualified from working with youth in any other setting; this

includes parents with violent criminal records or pending child abuse

investigations, or those found to have abused children in the past.

The number of students from preschool to 12th grade enrolled in the

state’s public schools has dropped by about 127,000 since the pandemic

began. Enrollment losses have outpaced declines in population, according

to a report by Advance Illinois, a nonprofit education policy and

advocacy organization. And, despite conventional wisdom, the drop was

also not the result of wealthier families moving their children to

private schools: After the pandemic, private school enrollment declined

too, according to the same report.

In the face of this historic exodus from public schools, Capitol News

Illinois and ProPublica set out to examine the lack of oversight by

education and child welfare systems when some of those children

disappear into families later accused of no-schooling and, sometimes,

abuse and neglect.

Reporters found no centralized system for investigating homeschooling

concerns. Educational officials said they were ill equipped to handle

cases where parents are accused of neglecting their children’s

education. They also said the state’s laws made it all but impossible to

intervene in cases where parents claim they are homeschooling. Reporters

also found that under the current structure, concerns about

homeschooling bounce between child welfare and education authorities,

with no entity fully prepared to step in.

“Although we have parents that do a great job of homeschooling, we have

many ‘no schoolers’” said Angie Zarvell, superintendent of a regional

education office about 100 miles southwest of Chicago that covers three

counties and 23 school districts. “The damage this is doing to small

rural areas is great. These children will not have the basic skills

needed to be contributing members of society.”

Regional education offices, like the one Zarvell oversees, are required

by law to identify children who are truant and try to help get them back

into school.

But once parents claim they are homeschooling, “our hands are tied,”

said Superintendent Michelle Mueller, whose regional office is located

about 60 miles north of St. Louis.

Even the state’s child welfare agency can do little: Reports to its

child abuse hotline alleging that parents are depriving their children

of an education have multiplied, but the Department of Children and

Family Services doesn’t investigate schooling matters. Instead, it

passes reports to regional education offices.

Todd Vilardo, who since 2017 has been superintendent of the school

district where L.J. was enrolled, said he is seeing more and more

children outside of school during the day. He wonders, “‘Aren’t they

supposed to be in school?’ But I’m reminded that maybe they’re

homeschooled,” said Vilardo, who has worked in the Charleston school

district for 33 years. “Then I’m reminded that there are very few

effective checks and balances on home schools.”

‘A huge crack in our system’

There’s no way to determine the precise number of children who are

homeschooled. In 2022, 4,493 children were recorded as withdrawn to

homeschool, a number that is likely much higher because Illinois doesn’t

require parents to register homeschooled children. That is a little more

than double the number a decade before.

In late fall of 2020, L.J. was one of the kids who slipped out of

school. After a roughly five-month hiatus from the classroom during the

pandemic, L.J.’s school resumed in-person classes. The third grader,

however, was frequently absent.

At home, tensions ran high. In the 640-square-foot apartment, L.J.’s

mother, Ashley White, and her boyfriend, Brian Anderson, juggled the

demands of three children including two born just about 10 months apart.

White, now 31, worked at a local fast-food restaurant. Anderson, now 51,

who uses a wheelchair, had applied for disability payments. Anderson

doesn’t have a valid driver’s license. The family lived in a subsidized

housing complex for low-income seniors and people with disabilities.

In an interview with reporters in late February, 14 months after L.J.

had been taken into custody by the state, the couple offered a range of

explanations for why he hadn’t been in school. L.J. had been suspended

and barred from returning, they said, though school records show no

expulsion. They also said they had tried to put L.J. in an alternative

school for children with special needs, but he didn’t have a diagnosis

that qualified him to attend.

The couple made clear they believed that L.J. was a problem child who

could get them in trouble; they said they thought he could get them

sued. In the interview, Anderson called L.J. a pathological liar, a

thief and a bad kid.

“I have 11 kids, never had a problem with any of them, never,” Anderson

said. “I’ve never had a problem like this,” he said of L.J. The boy, he

said, lacked discipline and continued to get “worse and worse and worse

every year” he’d known him.

To support the idea that L.J. was combative, White provided a copy of a

screenshot taken from a school chat forum in which the boy cursed at his

schoolmates.

At the end of the school year, in spring 2021, the principal told White

and Anderson that the boy would have to repeat the third grade. Rather

than have L.J. held back, the couple pulled him out of school to

homeschool. They didn’t have to fill out any paperwork or give a reason.

On any given day in Illinois, a parent can make that same decision.

That’s due to a series of court and legislative decisions that

strengthened parents’ rights against state interference in how they

educate their children.

In 1950, the Illinois Supreme Court heard a case involving

college-educated parents who kept their 7-year-old daughter at home.

Those parents, Seventh-day Adventists, argued that a public school

education produced a “pugnacious character” and believed the mother was

the best teacher and nature was the best textbook. The judges ruled in

their favor, finding that, in many respects under the law, homeschools

are essentially like private schools: not required to register kids with

the state and not subject to testing or curriculum mandates.

In 1989, the legislature voted to change how educational neglect cases

are handled. Before the vote, DCFS was allowed to investigate parents

who failed to ensure their child’s education just as it does other types

of neglect. In a bipartisan vote, the General Assembly changed that, in

part to reduce caseloads on DCFS — which has been overburdened and

inadequately staffed for decades — and also in response to concerns

about state interference from families who homeschool.

Since then, DCFS has referred complaints about schooling that come in to

its child abuse hotline over to regional offices of education. The

letter accompanying the educational neglect referral form ends with:

“This notice is for your information and pursuit only. No response to

this office is required.”

[to top of second column]

|

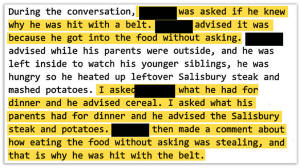

L.J. told police that he was sometimes left alone to care for his

baby siblings and punished for eating food without permission,

according to Charleston Police Department records. (Obtained by

Capitol News Illinois and ProPublica. Highlighted and redacted by

ProPublica.)

Tierney Stutz, executive deputy director at DCFS, said that regional

education officials are welcome to report back findings, but that “DCFS

does not have statutory authority to act on this information.”

“Unfortunately, this is a huge crack in our system,” said Amber Quirk,

regional superintendent of the office of education that covers densely

populated DuPage County in the Chicago suburbs.

To see how this system is working, reporters obtained more than 450 of

these educational neglect reports, representing over a third of the more

than 1,200 forwarded by DCFS over three years ending in 2023. About 10%

of them specifically cited substandard homeschooling claims. But

officials said that in many of the other reported cases of kids out of

school, they found that families also claimed they were homeschooling.

Faced with cases of truancy or educational neglect, county prosecutors

can press charges against parents. But if they do, parents can lean on

Illinois’ parental protections when they defend themselves in court from

a truancy charge.

That’s been the experience of Dirk Muffler, who oversees truancy

intervention at a regional office of education covering five counties in

west-central Illinois. “We’ve gone through an entire truancy process,

literally standing on the courthouse steps getting ready to walk in to

screen a kid into court and the parents say, ‘We are homeschooling.’ I

have to just walk away then.”

More recently, the ISBE made one more decision to loosen the monitoring

of parents who homeschool: For years, school districts and regional

offices distributed voluntary registration forms to families who

homeschool, some of whom returned them. Then last year, the state agency

told those regional offices that they no longer had to send those forms

to ISBE.

“The homeschool registration form was being misinterpreted in some

instances that ISBE was reviewing or approving homeschool programs,

which it does not have statutory authority to do,” an ISBE spokesperson

told the news organizations.

Over the years, the legislature has taken up proposals to strengthen the

state’s oversight of homeschooling. In 2011, lawmakers considered

requiring parents to notify their local school districts of their intent

to homeschool, and in 2019 they considered calling for DCFS to inspect

all homeschools and have ISBE approve their curriculum.

Each time, however, the state’s strong homeschooling lobby, mostly made

up of religious-based organizations, stepped in.

This March, under sponsorship of the Illinois Christian Home Educators,

homeschoolers massed at the state Capitol as they have for decades for

Cherry Pie Day, bringing pies to each of the state’s 177 lawmakers.

Kirk Smith, the organization’s executive director and former public

school teacher, summed up his group’s appeal to lawmakers: “All we want

is to be left alone. And Illinois has been so good. We have probably the

best state in the nation to homeschool.”

‘Nobody knows. He’s not in school.’

Just days after child protection workers took 11-year-old L.J. into

protective custody on his birthday, a 9-year-old homeschooled boy, 240

miles away, disappeared and was missing for months before police went

looking for him.

Though the case of Zion Staples was covered in the media, it has not

been previously reported that his homeschooling status delayed the

discovery of his death.

Zion had been living in Rock Island, in the northwest part of the state,

with his mother, Sushi Staples. The family had a long history of abuse

and neglect investigations by DCFS, and Staples had lost two kids to

foster care in Illinois nearly two decades before because she mistreated

them; the children were not returned to her. The most recent

investigation by DCFS was in 2021. The department did not find enough

evidence to find mistreatment and the case was closed.

Despite her past involvement with child welfare services, no Illinois

laws restricted her from homeschooling the children who remained in her

care, including Zion and five others who were then ages 8 to 14.

When reporters asked DCFS for his schooling status, the agency’s

responses revealed considerable confusion about where he was being

educated. DCFS originally told the news organizations that Zion was

enrolled in an online school program, but the company that DCFS said had

been providing his schooling told reporters that Zion had never been

enrolled. DCFS later clarified that his mother said he was leaving

public school in August 2021 to attend an online program, but no one was

required to verify this information.

On a December morning in 2022, Staples told police she returned home

from running errands and found Zion dead. A coroner would later find

that he died from an accidental, self-inflicted shot fired from a gun

the children found in the house. His mother hid the body and later

confided to her friend, Laterrica Wilson, that she did it because she

did not want to risk losing her other children.

“She said: ‘Nobody knows. He’s not in school. He’s homeschooled. I’ve

got this figured out,’” Wilson recalled in an interview with a reporter

about a conversation she had with Staples a few months after the child

had died. “She said she had too much to lose.”

Wilson, who lives in Florida, said it was one of several calls she had

with Staples over the course of months as she tried to figure out what

had happened and what to do about it. Police records indicate that in

July, in response to a call from Wilson, they visited the home. Staples

denied the child even existed. Later, when police executed a search

warrant, officers found Zion’s body in a metal trash can in the garage;

he was still wearing his Spiderman pajama bottoms. He’d been dead for

seven months, an autopsy revealed.

Staples was charged with concealing a death, failure to report the death

of a child within 24 hours and obstructing justice. Staples pleaded

guilty to felony endangering the health of a child in February and was

sentenced to two years in prison in April.

Staples did not respond to a letter sent to her in prison seeking

comment on this case.

DCFS and its university partners study all sorts of risks to children

involved with the child welfare system, but they’ve never examined

homeschooling and do not track the number of children the agency comes

in contact with who are homeschooled. While the agency’s inspector

general is required to file reports on every child who dies in foster

care or whose family the agency had investigated within the preceding

year of the child’s death, the children’s schooling status is rarely

noted in them.

For L.J., homeschooling rules also blinded school officials to abuse he

suffered, although their administrative office is within sight of his

apartment complex. About five months passed from when he was withdrawn

to homeschool in the summer of 2021 before the first signs of help

arrived. Following a call to its hotline in January 2022, DCFS found

White and Anderson neglectful, citing inadequate supervision, but that

did not result in L.J. returning to school. DCFS offered services, but

Anderson and White declined.

DCFS received more calls to its hotline in June 2022 and again that

September, alleging that Anderson and White had mistreated L.J. In both

of those cases, DCFS investigators did not find enough evidence to

support those allegations and closed the cases.

The caller in September told DCFS the boy appeared malnourished. L.J.

hadn’t been in school since 2019, the caller reported. But DCFS said

they did not pursue an investigation into his schooling matters because

it wasn’t in their policies to do so.

It did send an educational neglect report to Kyle Thompson, the

superintendent of schools overseeing the regional office of education in

Charleston. The form didn’t mention physical abuse, but it did say that

L.J. had begged for food from neighbors, that doctors were concerned

about his weight and that a DCFS caseworker had recently visited the

home but no one had answered the door.

Thompson was in his office when the educational neglect report ended up

on his desk on an October afternoon. Alarmed when he read the

allegations, Thompson went to the apartment that same day. White and

Anderson came to the door, Thompson recalled, and eventually agreed to

meet with school officials.

“I really feel like we may have saved that kid’s life that day,”

Thompson said.

But Anderson and White continued to keep L.J. at home.

In November, a grocery store manager found L.J. in the parking lot

begging for quarters and called police, who took L.J. home and later

issued a ticket to White and Anderson for violating a city truancy

ordinance. L.J. hadn’t been to school the whole year — 70 days.

Anderson said he didn’t know why he was cited, since he was

homeschooling. “Apparently, it wasn’t good enough for the school

system,” he told reporters.

A few days later, police and child welfare services again visited the

home and found welts and bruises on L.J.’s back. L.J. said Anderson had

beaten him with a belt as punishment for eating leftover Salisbury steak

and potatoes without permission. The boy also told child welfare workers

he had not showered for two weeks.

Anderson and White would later tell reporters L.J. was on a diet of

fruits and vegetables because he was too fat and prediabetic, but L.J.

told police he ate mostly cereal. Though DCFS found credible evidence of

both neglect and abuse in its November and December investigations, the

couple said they did not abuse L.J. or deny him an education. They are

still trying to get the two younger children back, but they say they

don’t want L.J. In an April court custody hearing, a judge in their

child welfare case admonished them for not accepting responsibility for

their treatment of L.J., including keeping him from school.

For its part, the state did ultimately take responsibility for L.J.’s

schooling: Caseworkers took the children into custody on a Friday. The

following Monday, L.J. returned to public school.

Mollie Simon of ProPublica contributed research.

Andrew Adams of Capitol News Illinois contributed data reporting.

Have a news tip regarding homeschooling, chronic

truancy or educational neglect? Email them to Molly Parker or Beth

Hundsdorfer at investigations@capitolnewsillinois.com. |