The Kremlin saw off Navalny - what now for Russia's opposition?

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 20, 2024]

By Mark Trevelyan [March 20, 2024]

By Mark Trevelyan

LONDON (Reuters) - On the night he celebrated extending his rule to at

least 2030, Russian President Vladimir Putin did something very unusual:

for the first time in memory, he spoke the name of Alexei Navalny in

public.

Answering a U.S. broadcaster's question after official results from

Russia's election gave him a landslide victory on Sunday, Putin

described Navalny's death in an Arctic penal colony last month as a "sad

event".

His comments outraged supporters of the late opposition leader, who

called them cynical and despicable.

For as long as Navalny was alive, the Kremlin shunned any mention of him

to make him seem politically irrelevant. Now that tactic is no longer

needed. The challenge for Navalny's movement is to show it remains a

force without him.

Twice in less than five weeks since his death, it has proved it can

still bring people out onto the streets - first for Navalny's March 1

funeral in Moscow and then for an election day protest where people were

urged to show up en masse at noon and vote against Putin or spoil ballot

papers.

Thousands heeded the call in Moscow and other big cities. "We have

proved to ourselves and others that Putin is not our president," said

Navalny's widow Yulia, saluting those who took part after joining one

such protest in Berlin on Sunday.

But across the whole of Russia, a country of 143 million people, the

"Noon against Putin" event was relatively modest.

"People are still prepared to make these public symbolic gestures but

the scale of it is just very limited," said Nigel Gould-Davies, a Russia

specialist at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

The action provided a safe, legal way of "keeping the flame alive" for

people who oppose Putin, and to show each other they were not alone, he

said. But it paled in comparison with the kind of mass protests that

convulsed Ukraine after elections in 2004 and Belarus in 2020, or with

the big Moscow rallies against Putin in 2011-12.

Further demonstrations are not on the cards. The authorities have

cracked down harshly on unauthorized gatherings, especially since the

start of the war in Ukraine, and protesters could expect a much tougher

police response than in the special circumstances of Navalny's funeral

and the day of the election, when people were queuing legally to cast

votes.

LONG HAUL

Navalny was far from being the only significant opposition figure but

the fact he survived a poisoning attempt, was treated abroad and still

chose to return to Russia and face jail gave him a special stature for

many. Other well-known Putin critics like former jailed businessman

Mikhail Khodorkovsky and ex-chess champion Garry Kasparov have lived

outside Russia for years.

Now Navalny's team is preparing for a long haul as Putin, 71, prepares

to start his fifth term. In a YouTube video, Yulia Navalnaya urged

people to adopt her husband's formula of "15 minutes a day of fighting

the regime".

"Every day, spend at least these 15 minutes to write a couple of lines,

talk to someone, convince someone and ultimately overcome your own fear.

Donít dismiss the work because it doesnít immediately lead to results,

but be patient and move forward. I definitely have enough patience," she

said.

The Kremlin's line of attack is already clear - to exploit the fact

Navalnaya is outside Russia as evidence she is out of touch. Pro-Kremlin

media have also subjected her to personal smears over her appearance and

actions since her husband's death.

Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters this week she was an

example of people losing their Russian roots and "ceasing to feel the

pulse of their own country".

[to top of second column]

|

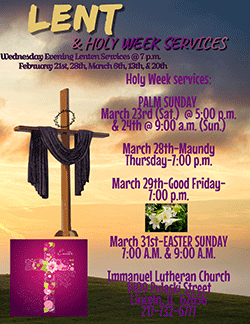

People walk towards the Borisovskoye cemetery during the funeral of

Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny in Moscow, Russia,

March 1, 2024. A placard reads: "Navalny died".

REUTERS/Stringer/File Photo

Ivan Fomin, an analyst with the Center for European Policy Analysis,

said it was important for the opposition outside Russia to connect

with "emergent opinion leaders" inside the country - for example

with the increasingly vocal groups of wives and mothers demanding

the return of mobilised soldiers from the front lines of the war in

Ukraine.

The opposition needed to avoid being "isolated in their bubble in

exile" and maintain connections with people still in Russia, he

said.

Navalny's former senior aide Leonid Volkov said the movement was

trying "not to become like an emigre organization" and staying

focused on the domestic agenda rather than issues faced by Russians

abroad, like the difficulty of opening bank accounts in the West.

"We invest a lot in staying relevant," he said in an interview this

month.

He said Navalny's organization, the Anti-Corruption Fund, has a

staff of about 140 and is working on some 20 projects - including an

investigation in which it aims to show that Navalny was murdered in

prison, and to name his killers.

The Kremlin denies any state involvement in his death.

WHAT OPPOSITION?

Underlining the risks to opposition figures even beyond Russia's

borders, Volkov suffered a hammer attack in the Lithuanian capital

Vilnius, hours after he spoke to Reuters last week.

Even to speak of an "opposition" is hardly appropriate in today's

Russia, said Vladimir Kara-Murza, a historian, journalist and

politician who is serving a 25-year sentence for treason but was

able to send written answers for publication by independent news

outlet Meduza.

Opposition is "a term from democratic life - the opposition sits in

parliaments, takes part in elections, and speaks in television

debates. All of Putin's main opponents have either been killed or

are in prison or abroad," he said.

Asked what ordinary people could do in the current situation, Kara-Murza

quoted from a 1974 paper by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a writer who

spent years in Soviet labor camps. The article was entitled "Live

not by lies".

His answer highlighted what some analysts see as increasing

parallels between Putin's opponents today and the lonely dissidents

who spoke out against Soviet repression, setting an example of hope

to others despite the certain prospect of losing their careers and

freedom.

"Re-read this (Solzhenitsyn) text, every word there is amazingly

relevant today. Because despite all the differences, the regimes

then and now have the same interconnected foundations - lies and

violence," Kara-Murza wrote.

He said Putin's real fight was not with the opposition but with the

future.

"It's impossible to stop the future. Russia will definitely become a

democracy, that 'normal European country' that Alexei Navalny liked

to talk about."

(Additional reporting by Andrius Sytas in Vilnius; Editing by Andrew

Cawthorne)

[© 2024 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved.]This material

may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content.

|