|

“Geology shouldn’t be out of

sight, out of mind”

Dr. Pam Moriearty shares geological

research with Logan County Genealogical & Historical Society

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 20, 2024]

At

the March 18 Logan County Genealogical and Historical Society

meeting, Dr. Pam Moriearty shared a presentation on Logan County’s

Secret Underground Geological Features. At

the March 18 Logan County Genealogical and Historical Society

meeting, Dr. Pam Moriearty shared a presentation on Logan County’s

Secret Underground Geological Features.

What Moriearty said she would be talking about is the history behind

history.

Though Moriearty is not a geologist, she got hooked

on geology about a year and half ago and considers herself a

geological aficionado.

On the state geological survey website, Moriearty found a button you

can click on and type in a question then get an answer from a real

geologist the next day.

Moriearty is thankful to local experts Dr. Dennis Campbell and Viper

Mine Manager Troy Kirkpatrick for helping her find information.

Other experts Moriearty has received information from are Dr. Steve

Altaner, Dr. Brandon Curry, Scott Elrick and Dr. Zak Lasemi, so she

is also thankful for their assistance.

As Moriearty started the presentation, she gave a definition of

geology, which is the science dealing with the earth’s substances,

structures made out of those substances, processes by which it [the

shaping of structures] happens and the history of it all.

In Logan County, Moriearty said we are in the middle of the North

American tectonic plate stuck. What Moriearty referred to as “sexy

geology” occurs at the edges of the plates. Faults, earthquakes,

volcanoes and one plate ramming into another pushing up a whole

mountain range happens at the edges.

Being in the middle of the plate means Logan County

is “stuck” with sedimentary rock such as limestone, sandstone and

shale. Moriearty said these rocks have been created by things

settling down and getting other layers on top of them.

An exception is that glaciers drop types of non-native rocks from

far away. Moriearty said these glaciers have left areas with some

igneous, volcanic and metamorphic rocks. She said here, we only have

native sedimentary rocks.

The geology of Logan County is “subtle” for another reason.”

Moriearty said over the years, we’ve “misplaced” about 300 million

years’ worth of rock layers. It has eroded away or been scraped away

by glaciers and is not there anymore.

Towards the top of the geological time scale is the era of glaciers

and wooly mammoths. Even further back was the pre-dinosaur era

rocks. However, Moriearty said there were no dinosaurs in this area.

To understand why crops in this area are so good, Moriearty said

looking under the corn and soybeans is helpful. We can find

geological clues looking under crops.

At one point, Dennis Campbell decided to look under the corn and

soybeans by digging up soil by the Sugar Creek bank. There was a

layer carved away, so Campbell carved out an area to study the creek

bank.

Something Moriearty said Campbell noticed was the creek washing mud

away from a tree trunk. Campbell took pieces of the wood and sent it

to some geologists. Moriearty said the geologists told Campbell what

he had found was a piece of a spruce tree.

After the geologists did some carbon dating, they told Campbell the

tree was 6,000 years old. Topsoil held the tree down by stuff left

from glaciers here years ago.

Moriearty said Illinois shows evidence of more than one glacier.

Silt was carried by water and distributed throughout Central

Illinois. Unlike sand, Moriearty said silt holds water.

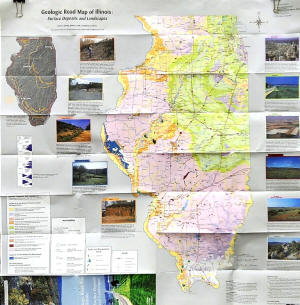

A geological road map of Illinois shows surface

deposits and landscapes. The green areas of the map show where there

was a glacier 15,000 years ago in the Wisconsin episode. Moriearty

calls it the green glacier.

The pink areas on the map show where there was a glacier 150,000

years ago in the Illinois episode. Moriearty calls it the pink

glacier. Logan County falls right on the edge and shows evidence of

both glaciers.

Red lines on the map are silt, which is finely ground rock.

Moriearty said when the glaciers melted, a lot of water flowed away

from the glacier and carried the silt with it. The silt often ended

up on the shore and dust storms and winds distributed it all over

central Illinois. Silt makes great topsoil because it will hold

water, which Moriearty said is the secret to our corn and soybeans.

Places like Lincoln Lakes provide clues to the

county’s geological history. Moriearty said these lakes were made

from sand and gravel pits. Around 1906, Lincoln Sand and Gravel

removed sand and gravel for construction through dredging it out of

the ground. The gravel was then further sorted for sale. She said

geologists looked at the gravel and wood samples from there and

dated them between 8,000 and 12,000 years old, which would be from

the “green” glacier.

At 777 feet above sea level, Moriearty said Elkhart

Hill is the highest point in the county. Some of the sand and gravel

there was deposited from the “pink” glacier 150,000 years ago. Since

the sand and gravel there has not been sorted or cleaned up,

Moriearty said it looks different than what would be found at

Lincoln Lakes.

Alongside Interstate 55 or Old Route 66 and some railroad tracks,

Moriearty said people will see the Viper Mine conveyer belt used for

coal mining. Years ago, she said much of the east part of Lincoln

had coal mines and “coal was king.”

Over 300 million years ago in the “Pennsylvanian Era,” Moriearty

said Logan County had a subtropical climate. It was home to lush

marshy forests and swamps. Every once in a while, Moriearty said

water levels rose and were covered by ocean water.

During the period before the glaciers melted, Moriearty said North

America was sitting near the equator. This period was before the

continents drifted apart. When glaciers melted, the water level

rose, and we got salt water. As it got cooler and glaciers formed

again, Moriearty said all the water was tied up in the glaciers, so

the water level went down and there was dry land in the area.

The result of shifting sea levels was a very complex set of layers

of sedimentary rock being set down. Moriearty said there may have

been sandstone, shale and freshwater limestone when we were under a

lake. She said limestone is made from dead critters in the water

falling down and their outer layers turning into rock.

When the water level went up and we were under the ocean, Moriearty

said we would have marine limestone and then shale if close to the

shore and mud washed in under the water. There would then be more

layers of limestone and of shale.

Below that, Moriearty said there was a layer of coal, then underclay,

freshwater limestone, sandy shale or siltstone and finally

sandstone.

To study these layers, Moriearty said geologists drill out a

cylindrical rock core and go through it layer by layer analyzing it

to see what it is, what was growing there and when it was happening.

On the top six layers, Moriearty said predominantly marine fossils

can be found. In the next several layers, fossils would be

predominantly non marine.

[to top of second column] |

For coal formation, Moriearty said time, pressure and

heat are needed. It starts out as peat, then produces lignite,

sub-bituminous and bituminous (soft) coal. Bituminous coal is the

kind we have. She said if water starts seeping down from layers

above the coal, it can carry impurities with it.

Calcium can come down. Moriearty said the calcium may

come from the limestone layer. If the calcium reacts with a plant

material, she said it turns the plant material into fossils. These

pieces cannot go on to be coal and they are harder. The fossils sit

there in the coal, which becomes a problem for coal miners.

When this coal is taken out and processed, it creates

coal balls. Moriearty said geologists love the coal balls because

they can be sliced in half to show what is inside.

Something else that can happen is Fools’ gold, which Moriearty said

is iron sulfide and adds sulfur to coal. We have high sulfur coal,

which must be scrubbed before letting it out of a chimney after it

is burned. She said the Fools’ gold comes from the layer of shale

above the coal. The Fools’ gold causes problems too.

Out past Fifth Street is Rocky Ford with square

lakes. For many years, Moriearty said Rocky Ford was a limestone

quarry. She asked whether the limestone was freshwater or saltwater

limestone.

Geologists do limestone analysis through chemical tests. Moriearty

said when acid is dripped onto limestone, the limestone foams. It is

the same principle used to get the scale out of coffee makers by

running vinegar through it to get out calcium deposits.

Geologists also do fossil analysis, which Moriearty said shows some

of the fossils came from the ocean.

The water in Logan County comes from the Mahomet Aquifer, which

Moriearty said gives more geological clues. To make an aquifer, she

said a waterproof bottom is needed, just like in a bathtub.

Something good to use is a groove in the bedrock

carved by an ancient river. In the bedrock of Illinois, Moriearty

said there are huge grooves that are ancient riverbeds. The grooves

are then filled with sand and gravel and saturated with water. For

the confined aquifer, she said a lid would be made from a layer of

clay.

Some aquifers do not have a lid and Moriearty said those are

unconfined aquifers. Most people on a well would have an unconfined

aquifer. When there is a dry period and the water table goes down,

the well goes down.

If you are on a confined aquifer, Moriearty said the

pressure of the water going through [the aquitard] pushes the water

above the water table.

Boring into these parts is what produces water.

Moriearty said the Mahomet Aquifer is critical to central Illinois

with more than half a million people getting water from it. She said

the latest figures show close to 800,000 people getting water from

the Mahomet Aquifer.

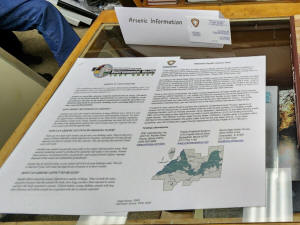

Threats to the aquifer come from both natural and

manmade pollution. Moriearty said things can seep from the ground to

the aquifer and one of the worst things is arsenic. Derivatives from

Fools’ gold can get into open wells, so she said regular testing of

wells is recommended to make sure they are not getting contaminated.

Manmade pollution can come from agriculture, factories, industry and

people in general.

Threats also come from recharging. Moriearty said when water is

sucked out of the aquifer faster than it comes in, it can suck

aquifers dry. Out west in the high plains, she said aquifers are

being used for irrigation.

Fortunately, Moriearty said the federal government has designated

the aquifer as a sole source water supply. It means the aquifer is

the only source of water possible for a lot of people. Because of

being the only source, she said it means we get funding and support

for it. There are test wells in the aquifer to constantly monitor

the water.

If you are going to start a new business, industry, factory or large

agricultural livestock farm, Moriearty said you have to submit plans

to the government. The government must approve the plan to help

ensure you are not putting concentrated pollutants into the aquifer.

We do not see much of our geology. Moriearty has driven past these

areas hundreds of times during her lifetime and said she has not

thought about what was going on that she could not see.

For Moriearty, the bottom line is “geology shouldn’t be out of

sight, out of mind—it’s not set in stone.” She said if we take care

of our geology, it will take care of us.

After Moriearty finished her presentation, she asked if there were

any questions.

LCGHS member Bill Donath asked about the depths of covered and

uncovered wells.

With these wells, Moriearty and others said it depends on where you

are. In some places it is 300 feet and in other places it is 200

feet. They are higher at the east end and lower at the west end.

One member had read about growing mushrooms in old coal mines.

If there is good temperature control, Moriearty said it would be

possible for mushrooms to grow in old mines.

In present day coal mines, Moriearty said walls of the mine shafts

are coated with white to prevent coal dust from igniting.

Once Moriearty finished her presentation, there was a short business

meeting followed by refreshments.

Questions about Moriearty’s research and presentation can be

addressed to her directly at

plmoriearty@gmail.com.

The next LCGHS meeting will be Monday, April 15. Gary Dodson will

share a presentation on the beginnings of the Edwards Trace.

[Angela Reiners]

More resources:

“Ask a Geologist.” Illinois State Geological Survey, University of

Illinois,

https://airtable.com/apppWBp5tw

X8IGIi8/shrTRzoJvyso1L9Nt

Kolata, Dennis R. and Cheryl Nimz Geology of Illinois. Champaign,

Il: University of Illinois, Illinois State Geological Survey, 2010.

McDonald, Mark. “Illinois Stories: Viper Mine” 2013, YouTube WSEC-TV/PBS.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=wLffarjDTDM

University of Illinois, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Local

Extension Councils cooperating.

|