Scientists chronicle the earliest stages of a supernova

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[March 28, 2024]

By Ari Rabinovitch [March 28, 2024]

By Ari Rabinovitch

REHOVOT, Israel (Reuters) - About 20 million years ago, in a galaxy not

so far away, a large star exploded and sent elements representing the

building blocks of life racing through space.

About a year ago, by chance, as the light it emitted reached Earth, a

team of scientists in Israel observed it and for the first time

collected data on the earliest stages from such an explosion, known as a

supernova.

The picture they are putting together offers a detailed look at the

origins of crucial elements around us, like the calcium in our teeth and

the iron in our blood.

"We are actually seeing the cosmic furnace in which the heavy elements

are formed, while they are being formed. We are observing it as it

happens. This is really the unique opportunity," Weizmann Institute of

Science astrophysicist Avishay Gal-Yam said.

The findings, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, also

indicate that the giant star, located in a neighboring galaxy called

Messier 101, likely left behind a black hole after it exploded.

An amateur astronomer who happened to be watching that galaxy tipped off

the researchers that something appeared to be occurring. They quickly

focused their ground-based telescopes at the star and started

documenting the early stages of the explosion.

The team, which included doctoral student and study lead author Erez

Zimmerman, contacted NASA, which changed its schedule and aimed the

Hubble Space Telescope at the supernova. This allowed early-stage

observation of ultraviolet light from the explosion, which is blocked by

the atmosphere and not picked up on Earth.

[to top of second column]

|

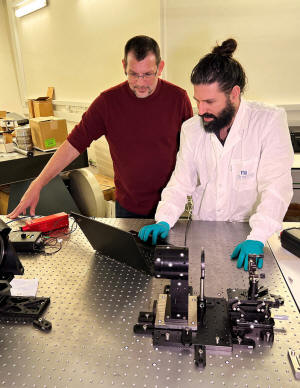

Astrophysicist Avishay Gal-Yam and researcher Ido Irani look at a

screen in their laboratory at the Weizmann Institute of Science in

Rehovot, Israel, March 27, 2024. REUTERS/Sebastian Rocandio

Along with tracking elements like carbon, nitrogen and oxygen

blasted into space, the ultraviolet data showed a discrepancy

between the star's initial mass and the mass it ejected into space

during the explosion.

"We suspect that after the explosion a black hole was left behind -

a newly formed black hole that wasn't there before. It's the remnant

of the explosion. A little bit of the mass of the star collapsed to

the center and created a new black hole," Gal-Yam said.

Black holes are extraordinarily dense objects with gravity so strong

that not even light can escape.

Having created a sort of fingerprint of the supernova from start to

finish, Gal-Yam said it could help scientists identify impending

supernovas elsewhere.

"Perhaps we will be able in the next few years to say, not for all

stars, but maybe for some of them, this star we think, we suspect,

it's going to explode," Gal-Yam added. "That will be fantastic, and

then we will know to be there and prepared."

(Reporting by Ari Rabinovitz; Editing by Will Dunham)

[© 2024 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved.]This material

may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |