Sun's magnetic field may originate closer to the solar surface

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[May 23, 2024]

By Will Dunham [May 23, 2024]

By Will Dunham

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The sun's magnetic field, which causes solar

storms like the one that hit Earth this month and produced beautiful

auroras, may originate at shallower depths in the star's interior than

previously thought, according to researchers.

The sun's outer 30% is comprised of an "ocean" of churning gases

plunging more than 130,000 miles (210,000 km) below the solar surface.

The research, comparing new theoretical models to observations by the

sun-observing SOHO spacecraft, provides strong evidence that its

magnetic field is generated near the top of this ocean - less than 5%

inward, or about 20,000 miles (32,000 km) - rather than near the bottom,

as long hypothesized.

In addition to providing insight into the sun's dynamic processes, the

findings may improve the ability to forecast solar storms and guard

against potential damage to electricity grids, radio communications and

orbiting satellites, the researchers said.

Most stars have magnetic fields, apparently generated by the motion of

super-hot gases inside them. The sun's ever-changing magnetic field

drives the formation of sunspots - shifting dark patches - on its

surface and triggers solar flares that blast hot charged particles into

space.

"The top 5% to 10% of the sun is a region where the winds are perfect

for making abundant magnetic fields through a fascinating astrophysical

process," said Geoffrey Vasil, an applied and computational

mathematician at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and lead author

of the study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature.

This process involves rotational flow patterns of super-hot ionized -

electrically charged - gases called plasma inside the sun.

The precise mechanisms behind how the sun generates its magnetic field -

the solar dynamo, as the scientists call it - has remained an unsolved

problem in theoretical physics. These researchers hypothesize that these

flow patterns are the key.

"If the plasma which constitutes the sun was completely stationary, we

know the sun's magnetic field would decay in time, and before long,

there would be no sunspots or other solar activity. However, the plasma

in the sun is moving around, and that motion is able to regenerate and

maintain the sun's magnetic field," said theoretical physicist and study

co-author Daniel Lecoanet of Northwestern University in Illinois.

[to top of second column]

|

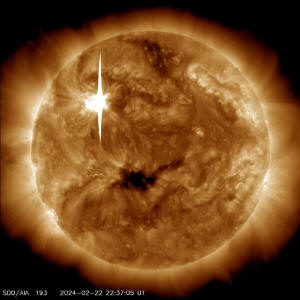

The Sun emits a solar flare February 22, 2024, in this image

captured by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory. NASA/SDO/Handout via

REUTERS/File Photo

The solar magnetic field ebbs and flows in a distinct pattern, with

sunspots - regions with very large magnetic fields - emerging and

then vanishing every 11 years, making the sun, as Vasil called it,

"a giant magnetic clock."

"But we have yet to find the full story about how it happens.

Complex interacting fluid motions (in this case, the solar plasma)

ultimately drive a dynamo, but we can't yet explain the details,"

Vasil added.

Italian polymath Galileo carried out in 1612 the first detailed

observations of sunspots using telescopes he invented. American

astronomer George Hale in the early 20th century determined that

sunspots were magnetic.

"And we're still scratching our heads about these pesky sunspots,"

Vasil said.

A strong solar storm that reached Earth this month caused bright

auroras in the skies, though Earth's technological infrastructure

remained unscathed.

"Occasionally, a group of sunspots explodes and launches a billion

tons of hot charged particles toward Earth, like what happened last

week," Vasil said.

But a powerful solar storm like one that occurred in 1859 called the

Carrington Event could cause trillions of dollars in damage and

leave hundreds of millions of people without power, the researchers

said.

"You can think of magnetic fields as being like rubber bands. The

motions near the surface of the sun can stretch out the rubber bands

until they break. The breaking magnetic field can then launch

material outward into space in what is called a solar storm. If

we're unlucky, these storms can be launched toward the Earth and can

cause significant damage to our satellites and power grid," Lecoanet

added.

(Reporting by Will Dunham; Editing by Lisa Shumaker)

[© 2024 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved.]This material

may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Thompson Reuters is solely responsible for this content. |