|

Chris Glick shares his research of

the history of the Lincoln Developmental Center with guests at the

May Historical Society meeting

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[May 22, 2024]

At the May 20, 2024, Logan County Genealogical and

Historical Society meeting, Chris Glick spoke on the history of the

Lincoln Developmental Center.

Diane Osborn introduced Glick, a Logan County Native.

Glick retired from the Navy after 20 years and worked for six years

at Choate Correctional Center in Anna, Illinois.

In her introduction, Osborn said Glick has always had a strong

interest in the State School/Lincoln Developmental Center. Osborn

said the Lincoln Developmental Center was originally called the

Asylum for Feeble Minded Children, which she found interesting.

Because Glick worked in a mental hospital and with the

developmentally disabled, he had some familiarity with the topic.

While researching LDC, Glick found a 2011 journal put

out by the State of Illinois with a chapter about the Lincoln

Developmental Center. He also spent a few hours at the public

library looking at a book on LDC’s history from beginning to its

2002 demise.

LDC had a long history as far as the different names and who

administrative responsibilities fell under. Glick said it was called

the Illinois Asylum for Feeble Minded Children from its founding in

1877 until 1909. It was then called the Lincoln State School and

Colony from 1909 to 1953. It was called Lincoln State School from

1953 to 1975. He said the final name was the Lincoln Developmental

Center from 1975 until it closed in 2002.

As for administrative responsibilities, Glick said

the Board of State Commissions and Public Charities oversaw it from

1871 to 1909. He said that was prior to the school coming into

Lincoln in 1877. From 1909 to 1917, the Board of Administrations

oversaw the school. From 1917 to 1961, it was administrated by the

Department of Public Welfare. From 1961 to 1965, the Department of

Mental Health oversaw it.

Finally, from 1965 to 2002, Glick said the school was administrated

by the Department of Developmental Disabilities and Mental Health.

Originally, Glick said when the school opened there was one building

strictly utilized for Civil War veterans with “coping and

compensating issues” or what we know today as Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder. He said people were not sure how to help them with those

issues back then.

June 5,1855 an act of legislation was created by the State Medical

Society. Glick said the State Medical Society’s actions established

the institution. Dr. David Pritz, Dr. E.R. Roe and Dr. J.V.C. Planey

were part of the group who started it.

Early on, Glick said the school was established as an institution

for idiots. He said in September 1865, Dr. Wilbur was elected as the

first superintendent of the institution.

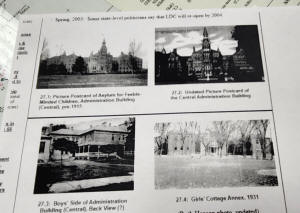

Construction began in 1875. Glick said it was

finished in 1877 at a cost of $170,000. He said it would likely cost

several million dollars to build it today.

The first building was 324 feet wide, 215 feet in depth. Glick said

the highest point at the center of the building was 100 feet high.

The outskirts were 75 feet high.

Glick said the building accommodated 300 pupils. It originally began

as an experimental center for children. Only later would it also be

for adults.

By 1884, Glick said they added a laundry building, which his great

grandmother worked in. A cottage hospital was finished in 1886.

Glick said that means they went nine years without having a hospital

set up for the residents.

Before the building was acquired, Glick said there was a lot of

legislation surrounding the establishment of the experimental

school. The school was intended for the instruction and training of

“idiots and feeble minded.”

Originally, Glick said there was an Experimental School for Idiots

and Feeble Minded Children [established by the State of Illinois] in

Jacksonville in 1865. By 1875, the school in Jacksonville was

overcrowded. Some of its residents moved to Lincoln in 1877 to

offset the overcrowding at the Jacksonville School.

The school in Lincoln was established as an

experimental center for the instruction and training of idiots and

feeble minded. As Glick said, those titles would probably cause a

lawsuit today. Glick said they worked with the children to develop

their minds and help them function better.

The capacity of the main building was 300. Glick said the

institution was geared for children between seven and fourteen who

were classified as idiotic and deficient in intelligence.

The goals of the institution were to improve children’s health and

teach them about bathing and the use of appropriate medication.

Glick said many children were not sure why they took the

medications.

One mile south of the facility 400 acres were leased in September

1877. Glick said a colony of boys lived at the farm and were

overseen by a husband and wife who owned the farm. Two hundred acres

was used for farming and crops. The other 200 acres were used for

pasture and raising livestock.

In 1887, Glick said all the beef for the facility came from the

farm. He said the place was almost completely self-sufficient

raising its own food and produce and having it prepared right there.

Eventually, Glick said the farm was expanded to nearly 500 acres.

Fifty acres were adjoining the farm, and 40 of those acres were in

Broadwell Township.

A farmer was hired to oversee the colony of 30 boys working at the

farm. At some point, Glick said growing wheat and corn ended when it

became unprofitable. It was then considered more practical to use

everything from the farm at the school. He said the school was like

a city of its own within the city since everything was provided by

the farm.

The state later purchased 725 acres of land and built two wards.

That way, Glick said individuals did not have to travel from the

farm back to the school and 625 men were housed there.

In 1917, Glick said numerous improvements were underway including

tunnels from the powerhouse, which still stands today. The tunnels

were dug as part of the steam power. He said residents helped run

new steam lines for heat into the buildings and power lines to build

up new bases for power in the buildings.

From the powerhouse, Glick said these tunnels branched off and led

to all the buildings at the facility.

One tunnel ran from the old hospital, infirmary and morgue and lead

out to the school’s cemetery by the prison. Glick said that way,

people from the facility could be brought out to be laid to rest

without everyone seeing them carry out the body.

Today, small sections of this tunnel can still be seen with a couple

of embankments when you are going from old 66 towards Highway 55,

but Glick said the area is blocked off. When people want to visit

the cemetery, he said they must get permission from people at the

prison and show their IDs. Guards function as escorts to and from

the cemetery.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal program was

established in the 1930s, Glick said the school then received

$30,000,000 for improvements.

The funding supplied the institution with boilers for heat. Glick

said some of the funds were used to help with power, sewage disposal

and heavy equipment for the reconstruction and refurbishment of the

old buildings. It helped relieve the overcrowding. The new housing

space brought their capacity from 1,000 to much more as the space

had 4,800 beds.

From 1945 to 1955, the Illinois Department of Welfare received $10M

for renovations at the facility. Glick said many medical

improvements were made during the following years. For example, a

pharmacy and dental facility were built, the surgical wards were

improved, and an X-Ray machine was brought in.

There were more doctors, dentists and other health care

professionals hired. Glick said some of these professionals included

counselors, social workers, psychologists and psychiatrists.

When veterans would come in and when psychologists worked with them,

Glick said they often did not know how to properly deal with their

issues. Most of these professionals had just worked with civilians

and not veterans. Unfortunately, Glick learned that when working at

Choate.

Veterans like Glick and two others would sometimes confront

psychologists, but he said they were told they were uneducated.

[to top of second column] |

Once the psychologists and psychiatrists finally

listened, Glick said people were able to get out of the facility

within weeks. One of Glick’s pet peeves when working in a mental

health facility was the mental health professionals not knowing how

to work with the veteran’s mental health issues.

Changes in mental health treatment over time

Next, Glick talked more about the changes he has seen over the years

in the approach to treating mental health. When Glick worked at

Choate years ago, he said treatment was very different. Treatments

then would include Electric Shock Therapy with paddles to the side

of the head leading to the brain. Some people had lobotomies.

Both children and adults were put in what was called a crib if they

fought the staff. Glick said small wooden cribs were set up for

children and larger ones were set up for adults. Once they were in

the crib, he said the top would be locked until they could stop

fighting staff.

The tunnels below the hospital had numbers on them. Glick said at

one time these areas had rings and shackles hanging from the walls

as one way to deal with out of control residents.

New guidelines have changed the way patients are

treated. Glick said now professionals try to create a distance and

talk to people who are upset to calm them down and relax them.

One patient Glick worked with would hit the block wall and go to the

other side of a room and do the same thing. She would not listen to

reason, so Glick said they put her in a physical hold.

To put patients in a physical hold, you come in from behind, cross

your arms and lay your head against theirs to keep them from banging

their head. The hold is only for one and half minutes before you

release pressure.

If patients have not calmed down after you do that, Glick said to

repeat the action until they have calmed them.

One man Glick recalls had been taken off all of his medications by

psychiatrists and psychologist while at a different facility. The

man became violent at the other place and was sent back to Choate.

When Glick was leaving work late one night, a technician called him

for help. Glick had to help the tech by talking to the man and

coaxing him back to the men’s hallway. The man responded by cussing

at Glick and slugging him. He knocked out one of Glick’s teeth and

bruised Glick’s ribs when Glick hit the concrete.

A code orange alert would bring everyone running to assist. If a

physical hold did not help, Glick said they used a humane wrap where

a wrap is tied around patients. The patients would then be carried

by six people to a cushioned and padded restraint room and have

their ankles and wrists bound but padded. You have to make sure

there is enough space that their circulation is not cut off.

If patients still do not calm down, Glick said they then use the

fifth point, a padded section that comes over the top to keep them

from beating their heads against the wall.

The last resort is what Glick said they called a 10-2-100 using a

combination of Adavan, Haldol and Benadryl. It was used to get

patients to calm down and go to sleep so they could go back to their

room. Glick said it was intended to keep them from becoming even

more violent and hurting themselves or others or even damaging

property.

In the present day, Glick said they try to treat people by talking

to them first to calm them down. The chemical restraints are a last

resort.

Other interesting facts

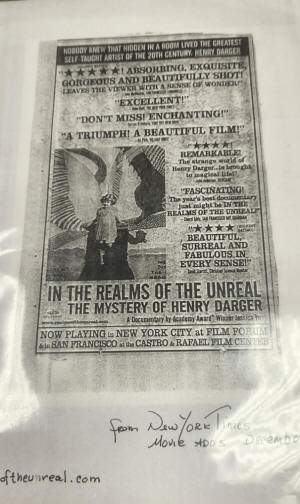

There were two very prominent individuals at LDC.

Glick said one was a patient named Henry Darger who made outside art

to exhibit.

One patient, who they named John Doe 24, was found

early one morning October 11, 1945, in Jacksonville. Glick said the

man was unable to communicate with anyone due to being deaf and

mute. The man was labelled feeble minded and sentenced by a judge to

the Lincoln State School. Glick said he remained in the Illinois

Mental Health system for over 30 years. John Doe 24 died in the

Sheridan Oaks Nursing Home in Peoria in 1993.

Singer/songwriter Mary Chapin Carpenter wrote a song about John Doe

24 titled “God Knows His Name.” Glick said when Carpenter found out

about the man and how he was laid to rest, she bought a headstone

for the man and had it placed in Peoria.

For many people whose name staff did not know, Glick said they were

referred to as John Doe with a number behind their names, which he

finds undignified.

Glick asked if there were any questions.

One person asked what president closed Lincoln Developmental Center.

When LDC closed, Glick said it was Illinois Governor George Ryan who

chose to close it. The President then was George W. Bush.

Gary Dodson said when Ronald Reagan was the president, he had

started paperwork and a push to close facilities.

With the tunnels Glick mentioned, Dodson said tunnels were put into

effect in all prisons in the state of Illinois so people could get

from one building to another.

In the prison system, Dodson said some past mental health treatments

are still utilized. He is a retired state policeman and said the

Department of Corrections still has their foot in some facilities.

There was a question from Dodson about how many residents had come

to Lincoln from Jacksonville.

In researching, Glick said he had not been able to

find that information. The facility in Jacksonville is now closed

too.

Though the children at the state school had farming abilities,

Dodson felt they did not get enough credit for these abilities.

To give the children self-sufficiency, Glick said many at the school

learned to make clothes, linens and shoes. Some people thought it

was inhumane to make them do that, but Glick and others said it gave

them a sense of self-worth.

Some people were sent there just because their family could not care

for them. One man said when evaluated, they did not have

developmental disabilities.

David Glick, whose mother-in-law worked at LDC, said some parents

treated the school as an orphanage. Many of the people there really

did not need to be there.

Dodson, who taught at LDC while he was a state policeman, remembers

trying to teach residents how to get along with people. He would

play games with some of the residents. Dodson said some of them were

“slow” but were not “idiots.” He feels an injustice was done when

the place was closed.

Someone said his wife found some of the residents acted better when

they moved to a good group home.

Usually, Chris Glick said a group home is a better environment.

However, some are not able to manage living in a group home. They

have to be able to work or go to workshop.

In 1969 and 1970, Cheryl Hall’s husband Gary was an administrator at

the state school. She said some residents were juvenile delinquents

from Chicago sent there because they could not pass tests due to

lack of education.

There was a question of when some of the buildings were erected.

In 1877, some buildings were erected. Later, Chris Glick said there

were ten buildings built for the colony and they housed up to 620

men. Funding from the state helped with the building. He is not sure

how many buildings are there.

Something David Glick recalled was that his stepmother had a family

member at LDC, who died at age 26. When the mother tried to visit

the cemetery, she found there were too many regulations. He said the

mother eventually stopped visiting the cemetery.

When Ruby Bartman-Nimke was a student nurse in the late 1950s, she

said she went out to the state school and saw a baby with

hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus, which is water on the brain, caused

the baby to have a very large head nearly as big as a card table.

Bartman-Nimke said the baby could not be moved. Fortunately, now

there is neurosurgery to drain the fluid.

For those interested in more of the history of LDC, Diane Osborne

said the genealogical society has a large collection from there

which includes tables, a podium, dishes, records, and scrapbooks.

She said the Logan County Tourism office has postcards, a copper

box, and part of the silver service from LDC.

Next month, Bill Gossett will speak about the past 100 years of

Lincoln history. The meeting will be held at the Logan County

Genealogical and Historical Society Monday, June 17 at 6:30 p.m.

[Angela Reiners]

|