For US adversaries, Election Day won't mean the end to efforts to

influence Americans

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 07, 2024]

By DAVID KLEPPER [October 07, 2024]

By DAVID KLEPPER

WASHINGTON (AP) — Soon, the ballots will be cast, the polls will close

and a campaign marked by assassination attempts, animosity and anxiety

will come to an end. But for U.S. adversaries, the work to meddle with

American democracy may be entering its most critical phase.

Despite all the attention on efforts to spread disinformation in the

months before the Nov. 5 election, the hours and days immediately after

voting ends could offer foreign adversaries like Russia, Iran and China

or domestic extremist groups the best chance to mess with America's

decision.

That's when Americans will go online to see the latest results or share

their opinions as the votes are tabulated. And that's when a fuzzy photo

or AI-generated video of supposed vote tampering could do its most

damage, potentially transforming online outrage into real-world action

before authorities have time to investigate the facts.

It's a threat taken seriously by intelligence analysts, elected

officials and tech executives, who say that while there's already been a

steady buildup of disinformation and influence operations, the worst may

be yet to come.

“It's not like at the end of election night, particularly assuming how

close this election will be, that this will be over,” said Sen. Mark

Warner, a Virginia Democrat who chairs the Senate Intelligence

Committee. “One of my greatest concerns is the level of misinformation,

disinformation that may come from our adversaries after the polls close

could actually be as significant as anything that happens up to the

closing of the polls.”

Analysts are blunter, warning that a particularly effective piece of

disinformation could be devastating to public confidence in the election

if spread in the hours after the polls close, and if the group behind

the campaign knows to target a particularly important swing state or

voting bloc.

Possible scenarios include out-of-context footage of election workers

repurposed to show supposed fraud, a deepfake video of a presidential

candidate admitting to cheating or a robocall directed at non-English

speakers warning them not to vote.

When a false or misleading claim circulates weeks before the election,

there's time for local election officials, law enforcement or news

organizations to gather the facts, correct any falsehoods and get the

word out. But if someone spreads a deceptive video or photo designed to

make a big chunk of the electorate distrust the results the day after

the election, it can be hard or even impossible for the truth to catch

up.

It happened four years ago, when a drumbeat of lies about the 2020

results spurred the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. Often,

those arrested on accusations of trying to interfere with the transfer

of power have cited debunked election fraud narratives that circulated

shortly after Election Day.

An especially close election decided in a handful of swing states could

heighten that risk even further, making it more likely that a rumor

about suitcases of illegal ballots in Georgia, to cite an example from

2020, could have a big impact on perceptions.

[to top of second column]

|

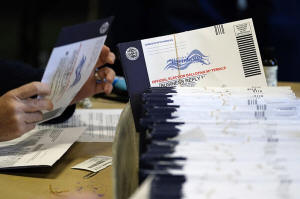

Chester County, Pa., election workers process mail-in and absentee

ballots, in West Chester, Pa., Nov. 4, 2020. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum,

File)

President Joe Biden's victory over Donald Trump in 2020 wasn't

especially close, and no irregularities big enough to affect the

result were found — and yet false claims about vote-rigging were

still widely believed by many supporters of the Republican, who's

running for president again.

The relatively long run-up to Inauguration Day on Jan. 20 gives

those looking to sow doubt about the results ample time to do so,

whether they are propaganda agencies in Moscow or extremist groups

in the U.S. like the Proud Boys.

Ryan LaSalle, CEO of the cybersecurity firm Nisos, said he won't

feel relief until a new president is sworn in without any serious

problems.

“The time to stay most focused is right now through the peaceful

transfer of power,” LaSalle said. “That’s when real-life activities

could happen, and that’s when they would have the greatest chance of

having an impact on that peaceful transfer.”

Another risk, according to officials and tech companies, is that

Russia or another adversary would try to hack into a local or state

election system — not necessarily to change votes, but as a way of

making voters question the security of the system.

“The most perilous time I think will come 48 hours before the

election,” Microsoft President Brad Smith told lawmakers on the

Senate Intelligence Committee last month. The hearing focused on

American tech companies’ efforts to safeguard the election from

foreign disinformation and cyberattacks.

Election disinformation first emerged as a potent threat in 2016,

when Russia hacked into the campaign of Democrat Hillary Clinton and

created networks of fake social media accounts to pump out

disinformation.

The threat has only grown as social media has become a leading

source of information and news for many voters. Content designed to

divide Americans and make them mistrust their own institutions is no

longer tied only to election seasons. Intelligence officials say

Russia, China and other countries will only expand their use of

online disinformation and propaganda going forward, a long-range

strategy that looks beyond any one election or candidate.

Despite the challenges, election security officials are quick to

reassure Americans that the U.S. election system is impervious to

any attack that could alter the outcome of the vote. While influence

operations may seek to spread distrust about the results,

improvements to the system make it stronger than ever when it comes

to efforts to change votes.

“Malicious actors, even if they tried, could not have an impact at

scale such that there would be a material effect on the outcome of

the election,” Jen Easterly, director of the U.S. Cybersecurity and

Infrastructure Security Agency, told The Associated Press.

All contents © copyright 2024 Associated Press. All rights reserved |