Navalny's memoir details isolation and suffering in a Russian prison —

and how he never lost hope

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 23, 2024]

By HILLEL ITALIE and DASHA LITVINOVA [October 23, 2024]

By HILLEL ITALIE and DASHA LITVINOVA

NEW YORK (AP) — In a memoir released eight months after he died in

prison, Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny never loses faith that

his cause is worth suffering for while also acknowledging he wished he

could have written a very different book.

“There is a mishmash of bits and pieces, a traditional narrative

followed by a prison diary,” Navalny writes in "Patriot," which was

published Tuesday, and is, indeed, a traditional narrative followed by a

prison diary.

“I so much do not want my book to be yet another prison diary.

Personally I find them interesting to read, but as a genre — enough is

surely enough.”

The final 200 pages of Navalny's 479-page book do, in some ways, have

the characteristics of other prison diaries or of such classic Russian

literature as Alexander Solzhenitsyn's “One Day in the Life of Ivan

Denisovich.” He tracks the boredom, isolation, exhaustion, suffering and

absurdity of prison life, while working in asides about everything from

19th century French literature to Billie Eilish. But “Patriot” also

reads as a testament to a famed dissident's extraordinary battle against

despair as the Russian authorities gradually increase their crackdown

against him, and even shares advice on how to confront the worst and

still not lose hope.

“The important thing is not to torment yourself with anger, hatred,

fantasies of revenge, but to move instantly to acceptance. That can be

hard,” he writes. “The process going on in your head is by no means

straightforward, but if you find yourself in a bad situation, you should

try this. It works, as long as you think everything through seriously.”

In recent years, Navalny had become an international symbol of

resistance. A lawyer by training, he started out as an anti-corruption

campaigner, but soon turned into a politician with aspirations for

public office and eventually became the main challenger to Russia’s

longtime president, Vladimir Putin.

Navalny’s widow, Yulia Navalnaya, oversaw the book’s completion. In a

promotional interview for “Patriot,” she told the BBC that she would run

for president if she ever returned to Russia -– an unlikely move with

Putin in power, Navalnaya acknowledged. She has been arrested in

absentia in Russia on charges of involvement with an extremist group.

Putin “needs to be in a Russian prison, to feel everything what not just

my husband, but all the prisoners in Russia” feel, Navalnaya said during

an interview on CBS' “60 Minutes.”

Navalnaya has vowed to continue her late husband’s fight. She has

recorded regular video addresses to her supporters and has been meeting

with Western leaders and top officials, advocating for Russians who

oppose Putin and his war in Ukraine. She had two children with her

husband, who in his book writes of his immediate attraction to her and

their enduring bond, praising Navalnaya as a soulmate who “could discuss

the most difficult matters with me without a lot of drama and

hand-wringing.”

During the first section of his book, Navalny reflects on the fall of

the Soviet Union, his disenchantment with 1990s Russian leader Boris

Yeltsin, his early crusades against corruption, his entry into public

life, and his discovery that he did not need to look far for a

politician “who would undertake all sorts of needed, interesting

projects and cooperate directly with the Russian people.”

“I wanted and waited, and one day I realized I could be that person

myself," he wrote.

His vision of a “beautiful Russia of the future,” where leaders are

freely and fairly elected, official corruption is tamed, and democratic

institutions work -– as well as his strong charisma and sardonic humor

-– earned him widespread support across the country's 11 time zones. He

had young, energetic activists by his side — a team that resembled “a

fancy startup” rather than a clandestine revolutionary operation,

according to his memoir. “From the outside we looked like a bunch of

Moscow hipsters,” he writes, and together they put out colorful,

professionally produced videos exposing official corruption. Those

garnered millions of views on YouTube and prompted mass rallies even as

the authorities cracked down harder on dissent.

[to top of second column]

|

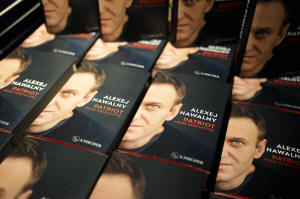

Copies of the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny's memoir

entitled 'Patriot' are put display on the first day of sale in a

bookshop in Berlin, Germany, Tuesday, Oct. 22, 2024. (AP

Photo/Markus Schreiber)

The authorities responded to Navalny’s growing popularity by levying

multiple charges against him, his allies and even family members. They

jailed him often and shut down his entire political infrastructure -–

the Foundation for Fighting Corruption he started in 2011 and a network

of several dozen regional offices.

In 2020, Navalny survived a nerve agent poisoning he blamed on the

Kremlin, which denied involvement. He describes it in great detail in

the very beginning of the book, recounting, “This is too much, and I'm

about to die.” His family and allies fought for him to be airlifted to

Germany for treatment, and after recovering there for five months, he

returned to Russia, only to be arrested and sent to prison, where he

would spend the last three years of his life.

In the memoir, Navalny recalls telling his wife while still hospitalized

in Berlin that “of course” he will go back to Russia.

The pressure on him continued behind bars, intensifying after Russia

invaded Ukraine in February 2022 and ratcheted its clampdown on dissent

to unprecedented levels. In messages he was able to get out of prison,

Navalny described harrowing conditions of solitary confinement, where he

was placed for months on end for various minor infractions prison

officials relentlessly accused him of, sleep deprivation, meager diet

and lack of medical help. In October 2023, three of his lawyers were

arrested and two more were put on a wanted list.

In December 2023, the authorities transferred Navalny to a penal colony

of the highest security level in the Russian penitentiary system in a

remote town above the Arctic Circle. In February 2024, 47-year-old

Navalny suddenly died there; the circumstances and the cause of his

death still remain a mystery. Yulia Navalnaya and his allies say the

Kremlin killed him, while the authorities argue that Navalny died of

“natural causes,” but wouldn’t reveal any details of what happened.

Tens of thousands of Russians attended his funeral on the outskirts of

Moscow in March in a rare show of defiance in a country where any street

rally or even single pickets often result in immediate arrests and

prison. For days afterward, people brought flowers to the grave, and a

handful even came Tuesday.

“I dream of as many people as possible reading this book, because it

seems to me that everyone will learn something new about Alexei.

(Everyone) will laugh and cry a bit. He was so cool: strong and brave,

kind and funny. The best. And the dearest,” Yulia Navalnaya said on X.

Navalny's team has said the book will be available in Russian, the

language he wrote it in, but shipping to his homeland and its neighbor

Belarus won't be possible “as we cannot guarantee delivery and the

absence of problems at customs.”

The Kremlin and Russian state media ignored the release, much as they

ignored many other developments related to Navalny, whose name Putin and

other top officials almost never uttered in public.

___

Litvinova reported from Tallinn, Estonia.

All contents © copyright 2024 Associated Press. All rights reserved |