Vote to continue strike exposes Boeing workers' anger over lost pensions

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 25, 2024] By

DAVID KOENIG and CATHY BUSSEWITZ [October 25, 2024] By

DAVID KOENIG and CATHY BUSSEWITZ

Since going on strike last month, Boeing factory workers have repeated

one theme from their picket lines: They want their pensions back.

Boeing froze its traditional pension plan as part of concessions that

union members narrowly voted to make a decade ago in exchange for

keeping production of the company's airline planes in the Seattle area.

Like other large employers, the aerospace giant argued back then that

ballooning pension payments threatened Boeing's long-term financial

stability. But the decision nonetheless has come back to have fiscal

repercussions for the company.

The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers

announced Wednesday night that 64% of its Boeing members voted to reject

the company's latest contract offer and remain on strike. The offer

included a 35% increase in wage rates over four years for 33,000

striking machinists but no restoration of pension benefits.

The extension of the six-week-old strike plunges Boeing — which is

already deeply in debt and lost another $6.2 billion in the third

quarter — into more financial danger. The walkout has stopped production

of the company’s 737, 767 and 777 jetliners, cutting off a key source of

cash that Boeing receives when it delivers new planes.

The company indicated Thursday, however, that bringing pensions back

remained a non-starter in future negotiations. Union members were just

as adamant.

“I feel sorry for the young people,” Charles Fromong, a tool-repair

technician who has spent 38 years at Boeing, said at a Seattle union

hall after the vote. “I've spent my life here, and I'm getting ready to

go, but they deserve a pension, and I deserve an increase.”

What are traditional pensions?

Pensions are plans in which retirees get a set amount of money each

month for the rest of their lives. The payments are typically based on a

worker's years of service and former salary.

Over the past several decades, however, traditional pensions have been

replaced in most workplaces by retirement-savings accounts such as

401(k) plans. Rather than a guaranteed monthly income stream in

retirement, workers invest money that they and the company contribute.

In theory, investments such as stocks and bonds will grow in value over

the workers’ careers and give them enough savings for retirement.

However, the value of the accounts can vary based on the performance of

financial markets and each employee’s investments.

Why did employers move away from pensions?

The shift began after 401(k) plans became available in the 1980s. With

the stock market performing well over the next two decades, “people

thought they were brilliant investors,” said Alicia Munnell, director of

the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. After the bursting

of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s took a toll on pension plan

investments, employers “started freezing their plans and shutting them

down,” she added.

In the 1980s, about 4 in 10 U.S. workers in the private sector had

pension plans, but today only 1 in 10 do, and they’re overwhelmingly

concentrated in the financial sector, said Jake Rosenfeld, chairman of

the sociology department at Washington University-St. Louis.

Companies realized that remaining on the hook to guarantee a certain

percentage of workers' salaries in retirement carried more risk and

difficulty than defined contribution plans that “shift the risk of

retirement onto the worker and the retiree,” Rosenfeld said.

“And so that became the major trend among firm after firm after firm,”

he said.

Rosenfeld said he was surprised the pension plan "has remained a

sticking point on the side of the rank and file” at Boeing. “These are

the types of plans that have been in decline for decades now. And so you

simply do not hear about a company reinstating or implementing from

scratch a defined contribution plan.”

What happened to Boeing's pension plan?

Boeing demanded in 2013 that machinists drop their pension plan as part

of an agreement to build a new model of the 777 jetliner in Washington

state. Union leaders were terrified by the prospect that Boeing would

build the plane elsewhere, with nonunion workers.

[to top of second column] |

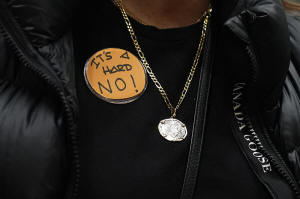

Boeing employee Gina Forbush wears an pin saying "IT'S A HARD NO!"

while listening to the announcement that union members voted to

reject a new contract offer from the company, Wednesday, Oct. 23,

2024, at Seattle Union Hall in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

After a bitter campaign, a bare 51%

majority of machinists in January 2014 approved a contract extension

that made union members hired after that ineligible for pensions and

froze increases for existing employees starting in October 2016. In

return, Boeing contributed a percentage of worker wages into

retirement accounts and matched employee contributions to a certain

point.

The company later froze pensions for 68,000

nonunion employees. Boeing's top human-resources executive at the

time said the move was about “assuring our competitiveness by

curbing the unsustainable growth of our long-term pension

liability.”

How realistic is the Boeing workers' demand?

Boeing raised its wage offer twice after the strike started on Sept.

13 but has been steadfast in opposing the return of pensions.

“There is no scenario where the company reactivates a

defined-benefit pension for this or any other population,” Boeing

said in a statement Thursday. "They're prohibitively expensive, and

that’s why virtually all private employers have transitioned away

from them to defined-contribution plans.”

Boeing says 42% of its machinists have been at the company long

enough to be covered by the pension plan, although their benefits

have been frozen for many years. In the contract that was rejected

Wednesday, the company proposed to raise monthly payouts for those

covered workers from $95 to $105 per year of service.

The company said in a securities filing that its accrued

pension-plan liability was $6.1 billion on Sept. 30. Reinstating the

pension could cost Boeing more than $1.6 billion per year, Bank of

America analysts estimated.

Jon Holden, the president of IAM District 751, which represents the

striking workers, said after the vote that if Boeing is unwilling to

restore the pension plan, “we’ve got to get something that replaces

it.”

Do companies ever restore pension plans?

It is unusual for a company to restore a pension plan once it was

frozen, although a few have. IBM replaced its 401(k) match with a

contribution to a defined-benefits plan earlier this year.

Pension plans have become a rarity in corporate America, so the move

may help IBM attract talent, experts say. But IBM's motivation may

have been financial; the pension plan became significantly

overfunded after the company froze it about two decades ago,

according to actuarial firm Milliman.

“The IBM example is not really an indication that there was a

movement toward defined benefit plans,” Boston College's Munnell

said.

Milliman analyzed 100 of the largest corporate defined benefits

plans this year and found that 48 were fully funded or better, and

36 were frozen with surplus assets.

Can Boeing be pressured to change its mind?

Pressure to end the strike is growing on new CEO Kelly Ortberg.

Since the walkout began, he announced about 17,000 layoffs and steps

to raise more money from the sale of stock or debt.

Bank of America analysts estimate that Boeing is losing about $50

million a day during the strike. If it goes 58 days — the average of

the last several strikes at Boeing — the cost could reach nearly $3

billion.

“We see more benefit to (Boeing) improving the deal further and

reaching a faster resolution,” the analysts said. “In the long run,

we see the benefits of making a generous offer and dealing with

increased labor inputs outpacing the financial strain caused by

prolonged disruptions.”

___

Manuel Valdes in Seattle contributed to this report. Koenig reported

from Dallas, and Bussewitz reported from New York.

All contents © copyright 2024 Associated Press. All rights reserved |