People opt out of organ donation programs after reports of a man

mistakenly declared dead

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[October 29, 2024]

By LAURAN NEERGAARD [October 29, 2024]

By LAURAN NEERGAARD

WASHINGTON (AP) — Transplant experts are seeing a spike in people

revoking organ donor registrations, their confidence shaken by reports

that organs were nearly retrieved from a Kentucky man mistakenly

declared dead.

It happened in 2021 and while details are murky surgery was avoided and

the man is still alive. But donor registries in the U.S. and even across

the Atlantic are being impacted after the case was publicized recently.

A drop in donations could cost the lives of people awaiting a

transplant.

“Organ donation is based on public trust,” said Dorrie Dils, president

of the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations, or OPOs. When

eroded, “it takes years to regain.”

Only doctors caring for patients can determine if they're dead -- the

law blocks anyone involved with organ donation or transplant. The

allegations raise questions about how doctors make that determination

and what’s supposed to happen if anyone sees a reason for doubt.

Key is ensuring “all doctors are doing the right tests and doing them

well,” said Dr. Daniel Sulmasy, a Georgetown University bioethicist.

An alleged near miss in Kentucky

The 2021 case first came to light in a congressional hearing last month,

with unconfirmed details in later media reports – allegations that a man

who’d been declared dead days earlier woke up on the way to the

operating room for organ-donation surgery and that there was initial

reluctance to realize it.

The federal agency that regulates the U.S. transplant system is

investigating, and the Kentucky attorney general’s office said it is

“reviewing the facts to identify an appropriate response.” A coalition

of OPOs and other donation groups is urging that findings be made public

quickly and the public withhold judgment until then, saying any

deviation from the industry's strict standards would be “entirely

unacceptable.”

The number of people opting out of organ donation has spiked

Donate Life America found an average of 170 people a day removed

themselves from the national donor registry in the week following media

coverage of the allegations – 10 times more than the same week in 2023.

That doesn’t include emailed removal requests or state registries,

another way people can volunteer to become a donor when they eventually

die.

Dils' own organ agency, Gift of Life Michigan, usually gets five to 10

calls a week from people asking how to remove themselves from that

state’s list. In the last week, her staff handled 57 such calls, many

mentioning the Kentucky case.

The Kentucky allegations reverberated in France

Unlike the voluntary U.S. donation system, French law presumes all

citizens and residents will be organ and tissue donors upon death unless

they clearly opt out.

After the reports from Kentucky reached France, the number joining that

nation’s donation refusal registry jumped from about 100 people a day to

1,000 a day in the past week, according to the French Biomedicine

Agency.

[to top of second column]

|

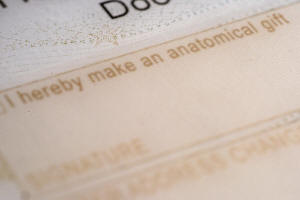

The organ donor entry on the back of a driver license is

photographed in New York on Friday, Oct. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Patrick

Sison)

Dr. Régis Bronchard, an agency

deputy director, said the spike “reflects anxiety, incomprehension

among the general public” that could have “catastrophic

consequences.”

What’s supposed to happen after death and before organ donation

Doctors can declare two types of death. What’s called cardiac death

occurs when the heart stops beating and breathing stops, and they

can’t be restored.

Brain death is declared when the entire brain permanently ceases

functioning, usually after a major traumatic injury or stroke.

Ventilators and other machines keep the heart beating during special

testing to tell.

Only about 1% of deaths occur in a way that allows someone to become

an organ donor – most people declared dead in a hospital will

quickly be transferred to a funeral home or morgue.

But most organ donations are from brain-dead donors. Only after that

declaration does the donor agency assume responsibility for the

deceased, looking for potential recipients and scheduling retrieval

surgery — while typically nurses at the hospital where the person

died continue care to ensure equipment properly maintains their

organs until they're collected.

What if something goes wrong?

The donor agency and transplant surgeons arriving to retrieve organs

must check records of how death was determined. Anyone – donor

hospital employees, donor agency staff or surgeons – who sees

anything concerning is supposed to speak up immediately.

“This is extremely rare,” Dr. Ginny Bumgardner, an Ohio State

University transplant surgeon who also leads the American Society of

Transplant Surgeons, said of the Kentucky case.

In operating rooms “the whole process stops” if someone sees a hint

of trouble, and independent doctors are called to doublecheck the

person really is dead, Bumgardner said. In her 30-year career, “I’ve

never had a case where the original declaration was wrong.”

Georgetown’s Sulmasy agreed problems are infrequent. But he said

there’s wide variation in what tests different hospitals perform to

determine if someone’s brain-dead, whether they’re a potential organ

donor or not. Doctors are debating whether to add additional test

requirements.

Stricter criteria could “assure the public that we have done

enormous due diligence before we determine that somebody’s dead,” he

said. It could help “to get people to stop ripping up their organ

donor cards.”

—-

John Leicester, the AP's chief correspondent in Paris, contributed

to this report.

All contents © copyright 2024 Associated Press. All rights reserved |