The benefits of a four-day workweek according to a champion of the trend

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[September 24, 2024]

By CATHY BUSSEWITZ [September 24, 2024]

By CATHY BUSSEWITZ

Companies exploring the option of letting employees work four days a

week hope to reduce job burnout and retain talent seeking a better

work-life balance, according to the chief executive of an organization

that promotes the idea.

The trend is gaining traction in Australia and Europe, says Dale

Whelehan, CEO of 4 Day Week Global, which coaches companies through the

months-long process of shortening their employeesí work hours. Japan

launched a campaign in August encouraging employers to trim work

schedules to four days.

American companies havenít adopted four-day weeks as broadly, but that

could change. Eight percent of full-time employees polled by Gallup in

2022 said they work four days a week, up from 5% in 2020.

The Associated Press spoke with Whelehan about the reasons why companies

might want to consider the change. His comments have been edited for

length and clarity.

Q: Why should organizations switch to a four-day workweek?

A: The bigger question is, why shouldnít they? Thereís a lot of evidence

to suggest we need to do something fundamentally different in the way we

work. We have issues of burnout. We have a recruitment and retention

crisis in many industries. We have increased stress within our

workforce, leading to health issues, issues with work-life balance,

work-family conflict. We have people sitting in cars for long periods,

contributing to a climate crisis. We have certain parts of the

population that are able to work longer hours and therefore be rewarded

for that, creating further inequity within our societies. Lastly, we

look at the implications that stress actually has on long-term health.

We know that itís linked to issues like cardiovascular disease, to

cancer, to diabetes. So stress is something not to be taken lightly, and

itís only rising in our world of work.

Q: Why is the 40-hour workweek so common?

To understand where we are now, letís take a step back into

pre-industrial times. My granddad was a farmer, worked seven days a week

and was required on-site all the time. It was a lot of long hours, but

also he had a lot of autonomy.

By the time my dad entered the workforce, he was a technician in a

mechanical role. And he was expected to produce products on a large

scale. As a result he wasnít given the rewards from farming, but was

given a salary. That change from my grandfatherís time to my dadís

brought about the birth of a discipline known as management. And

management, led by Frederick Taylor, was looking at the relationship

between fatigue and performance. A lot of scientific studies were done

to try to understand that relationship, leading to the need for a

five-day week as opposed to a six-day week. By the time I entered into

the workforce, we no longer had a very physical, laborious workforce.

It's highly cognitive and highly emotional.

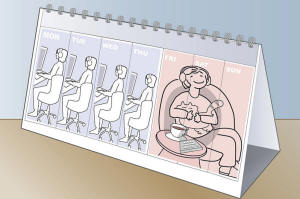

[to top of second column]

|

(AP Illustration/Jenni Sohn)

The fundamental physiological

difference is that our brain as a muscle canít withstand the same

level of hours of work as our muscles in our body might be able to.

So itís that mismatch between an outdated work structure of 40

hours, rooted in very physical labor, and what is now a highly

cognitive workforce.

Q: How can companies increase revenue while

employees work fewer hours?

A: The reduction of working time brings about productivity gains by

people having naturally more time to rest and recover, allowing them

to come back into a new week more engaged and well-rested. Thatís

one way in which you see productivity gains. The second is the

fundamental shift that organizations undergo while transitioning to

a four-day week.

When we work with organizations, we use whatís called a 100-80-100

principle. So 100% pay for 80% time for 100% output. We ask

organizations to design their trials in that sort of philosophy: How

can you keep your business at the same level or improve while

working less? The fundamental change we see is, letís move away from

thinking about productivity as how much time it takes to get

something done, versus focusing on what outcomes we know drive

businesses forward.

Q: How does a four-day workweek support equity?

A: Disproportionately high amounts of part-time workers are female.

As a result, women typically take a reduction in pay. Thatís despite

the fact that, based on the evidence that weíve seen in trials,

those part-time workers are producing the same output as their

five-day-week counterparts.

In four-day week trials, everyone embarks on the journey. So we see

men taking on greater levels of responsibilities in household or

parenting responsibilities.

The alternative situation is women take part-time work, reduce their

pay. Men have to work longer hours at a higher salaries and more

stressful jobs in order to make up the deficit. ... It just creates

this vicious cycle.

Q: What kinds of work could potentially be dropped to increase

productivity?

A: Meetings. We are addicted to meetings. Itís just gotten worse and

worse since the pandemic. I think a lot of that comes from a culture

of indecisiveness. Thereís a sense of not wanting to make decisions,

and therefore delaying the process or involving many people in the

process so that everyone has a responsibility, and thus no one has

responsibility. And that is not good when it comes to the greater

issue of productivity.

All contents © copyright 2024 Associated Press. All rights reserved |