Miami’s ‘Little Venezuela’ fears Trump's moves against migration

[April 07, 2025]

By GISELA SALOMON

DORAL, Fla. (AP) — Wilmer Escaray left Venezuela in 2007 and enrolled at

Miami Dade College, opening his first restaurant six years later.

Today he has a dozen businesses that hire Venezuelan migrants like he

once was, workers who are now terrified by what could be the end of

their legal shield from deportation.

Since the start of February the Trump administration has ended two

federal programs that together allowed more 700,000 Venezuelans to live

and work legally in the U.S. along with hundreds of thousands of Cubans,

Haitians and Nicaraguans.

In the largest Venezuelan community in the United States, people dread

what could face them if lawsuits that aim to stop the government fail.

It's all anyone discusses in “Little Venezuela” or “Doralzuela,” a city

of 80,000 people surrounded by Miami sprawl, freeways and the Florida

Everglades.

Deportation fears in Doralzuela

People who lose their protections would have to remain illegally at the

risk of being deported or return home, an unlikely route given the

political and economic turmoil in Venezuela.

“It’s really quite unfortunate to lose that human capital because there

are people who do work here that other people won’t do,” Escaray, 37,

said at one of his “Sabor Venezolano” restaurants.

Spanish is more common than English in shopping centers along Doral's

wide avenues, and Venezuelans feel like they're back home but with more

security and comfort.

A sweet scent wafts from round, flat cornmeal arepas sold at many

establishments. Stores at gas stations sell flour and white cheese used

to make arepas and T-shirts and hats with the yellow, blue and red

stripes of the Venezuelan flag.

New lives at risk

John came from Venezuela nine years ago and bought a growing

construction company with a partner. He and his wife are on Temporary

Protected Status, or TPS, which Congress created in 1990 for people in

the United States whose homelands are considered unsafe to return due to

natural disaster or civil strife. Beneficiaries can live and work while

it lasts but TPS carries no path to citizenship.

Born in the U.S., their 5-year-old daughter is a citizen. John, 37,

asked to be identified by first name only for fear of being deported.

His wife helps with administration at their construction business while

working as a real-estate broker. The couple told their daughter that

they may have to leave the United States. Venezuela is not an option.

“It hurts us that the government is turning its back on us,” John said.

“We aren’t people who came to commit crimes; we came to work, to build.”

A federal judge ordered on March 31 that temporary protected statuswould

stand until a legal challenge's next stage in court and at least 350,000

Venezuelans were temporarily spared becoming illegal. Escaray, the owner

of the restaurants, said nearly all of his 150 employees are Venezuelan

and more than 100 are on TPS.

The federal immigration program that allowed more than 500,000 Cubans,

Venezuelans, Haitians and Nicaraguans to work and live legally in the

U.S. — humanitarian parole — expires April 24 absent court intervention.

[to top of second column]

|

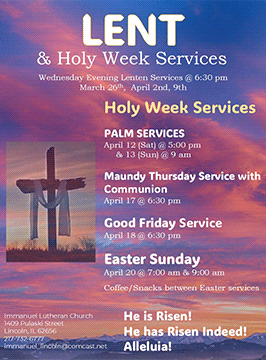

U.S. citizens who immigrated from Venezuela between 16 and 30 years

ago play dominos outside El Arepazo, a restaurant that is a hub of

the largest Venezuelan community in the U.S., in Doral, Fla.,

Wednesday, April 2, 2025. Many of the friends, including Cesar Mena,

at right, voted for President Donald Trump and continue to support

him. "I have family and friends on TPS [Temporary Protected Status]

and I feel bad for them. But it's a temporary situation, and you

need to resolve the problem." (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Politics of migration

Venezuelans were one of the main beneficiaries when former President

Joe Biden sharply expanded TPS and other temporary protections.

Trump tried to end them in his first term and now his second.

The end of the temporary protections has generated little political

reaction among Republicans except for three Cuban-American

representatives from Florida who called for avoiding the

deportations of affected Venezuelans. Mario Díaz Ballart, Carlos

Gimenez and Maria Elvira Salazar have urged the government to spare

Venezuelans without criminal records from deportation and review TPS

beneficiaries on a case-by-case basis.

The mayor of Doral, home to a Trump golf club since 2012, wrote a

letter to the president asking him to find a legal pathway for

Venezuelans who haven’t committed crimes.

“These families do not want handouts,” said Christi Fraga, a

daughter of Cuban exiles. “They want an opportunity to continue

working, building, and investing in the United States.”

A country's elite, followed by the working class

About 8 million people have fled Venezuela since 2014, settling

first in neighboring countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, they increasingly set their sights on

the United States, walking through the notorious jungle in Colombia

and Panama or flying to the United States on humanitarian parole

with a financial sponsor.

In Doral, upper-middle-class professionals and entrepreneurs came to

invest in property and businesses when socialist Hugo Chávez won the

presidency in the late 1990s. They were followed by political

opponents and entrepreneurs who set up small businesses. In recent

years, more lower-income Venezuelans have come for work in service

industries.

They are doctors, lawyers, beauticians, construction workers and

house cleaners. Some are naturalized U.S. citizens or live in the

country illegally with U.S.-born children. Others overstay tourist

visas, seek asylum or have some form of temporary status.

Thousands went to Doral as Miami International Airport facilitated

decades of growth.

Frank Carreño, president of the Venezuelan American Chamber of

Commerce and a Doral resident for 18 years, said there is an air of

uncertainty.

“What is going to happen? People don't want to return or can't

return to Venezuela,” he said.

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved |