Apollo 13 moon mission leader James Lovell dies at 97

[August 09, 2025]

By DON BABWIN

CHICAGO (AP) — James Lovell, the commander of Apollo 13 who helped turn

a failed moon mission into a triumph of on-the-fly can-do engineering,

has died. He was 97.

Lovell died Thursday in Lake Forest, Illinois, NASA said in a statement

on Friday.

“Jim’s character and steadfast courage helped our nation reach the Moon

and turned a potential tragedy into a success from which we learned an

enormous amount,” NASA said. "We mourn his passing even as we celebrate

his achievements.”

One of NASA's most traveled astronauts in the agency's first decade,

Lovell flew four times — Gemini 7, Gemini 12, Apollo 8 and Apollo 13 —

with the two Apollo flights riveting the folks back on Earth.

Lovell and fellow astronauts Fred Haise and Jack Swigert received

renewed fame with the retelling of the Apollo 13 mission in the 1995

movie “Apollo 13" where actor Tom Hanks — portraying Lovell — famously

said, “Houston, we have a problem.”

In 1968, the Apollo 8 crew of Lovell, Frank Borman and William Anders

was the first to leave Earth's orbit and the first to fly to and circle

the moon. They could not land, but they put the U.S. ahead of the

Soviets in the space race. Letter writers told the crew that their

stunning pale blue dot photo of Earth from the moon, a world first, and

the crew's Christmas Eve reading from Genesis saved America from a

tumultuous 1968.

The Apollo 13 mission had a lifelong impact on Lovell

But the big rescue mission was still to come. That was during the

harrowing Apollo 13 flight in 1970. Lovell was supposed to be the fifth

man to walk on the moon. But Apollo 13's service module, carrying Lovell

and two others, experienced a sudden oxygen tank explosion on its way to

the moon. The astronauts barely survived, spending four cold and clammy

days in the cramped lunar module as a lifeboat.

''The thing that I want most people to remember is (that) in some sense

it was very much of a success,'' Lovell said during a 1994 interview.

''Not that we accomplished anything, but a success in that we

demonstrated the capability of (NASA) personnel.''

A retired Navy captain known for his calm demeanor, Lovell told a NASA

historian that his brush with death affected him.

“I don't worry about crises any longer,” he said in 1999. Whenever he

has a problem, “I say, ‘I could have been gone back in 1970. I'm still

here. I'm still breathing.' So, I don't worry about crises.”

Lovell had ice water in his veins like other astronauts, but he didn't

display the swagger some had, just quiet confidence, said Smithsonian

Institution historian Roger Launius. He called Lovell “a very

personable, very down-to-earth type of person, who says 'This is what I

do. Yes, there's risk involved. I measure risk.'”

Lovell spent about 30 days in space across 4 missions

In all, Lovell flew four space missions — and until the Skylab flights

of the mid-1970s, he held the world record for the longest time in space

with 715 hours, 4 minutes and 57 seconds.

“He was a member of really the first generation of American astronauts

and went on to inspire multiple generations of Americans to look at the

stars and want to explore,” said Bruce McClintock, who leads the RAND

Corp. Space Enterprise Initiative.

Aboard Apollo 8, Lovell described the oceans and land masses of Earth.

"What I keep imagining, is if I am some lonely traveler from another

planet, what I would think about the Earth at this altitude, whether I

think it would be inhabited or not," he remarked.

That mission may be as important as the historic Apollo 11 moon landing,

a flight made possible by Apollo 8, Launius said.

"I think in the history of space flight, I would say that Jim was one of

the pillars of the early space flight program," Gene Kranz, NASA's

legendary flight director, once said.

Lovell was immortalized by Tom Hanks' portrayal

But if historians consider Apollo 8 and Apollo 11 the most significant

of the Apollo missions, it was during Lovell's last mission that he came

to embody for the public the image of the cool, decisive astronaut.

The Apollo 13 crew of Lovell, Haise and Swigert was on the way to the

moon in April 1970, when an oxygen tank from the spaceship exploded

200,000 miles from Earth.

That, Lovell recalled, was “the most frightening moment in this whole

thing.” Then oxygen began escaping and “we didn't have solutions to get

home.”

[to top of second column]

|

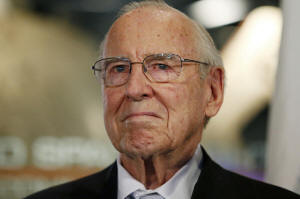

Capt. James A. Lovell, Jr., attends the 45th Anniversary of Apollo 8

"Christmas Eve Broadcast to Earth" event at the Museum of Science

and Industry in Chicago, Monday, Dec. 23, 2013. (AP Photo/Kamil

Krzaczynski, File)

“We knew we were in deep, deep trouble,” he told NASA's historian.

Four-fifths of the way to the moon, NASA scrapped the mission. Suddenly,

their only goal was to survive.

Lovell's "Houston, we've had a problem," a variation of a comment

Swigert had radioed moments before, became famous.

What unfolded over the next four days captured the imagination of the

world.

With Lovell commanding the spacecraft, Kranz led hundreds of flight

controllers and engineers in a furious rescue plan.

The plan involved the astronauts moving from the service module, which

was hemorrhaging oxygen, into the cramped, dark and frigid lunar lander

while they rationed their dwindling oxygen, water and electricity. Using

the lunar module as a lifeboat, they swung around the moon, aimed for

Earth and raced home.

“There is never a guarantee of success when it comes to space,”

McClintock said. Lovell showed a “leadership role and heroic efforts in

the recovery of Apollo 13.”

By coolly solving the problems under the most intense pressure

imaginable, the astronauts and the crew on the ground became heroes. In

the process of turning what seemed routine into a life-and-death

struggle, the entire flight team had created one of NASA's finest

moments.

"They demonstrated to the world they could handle truly horrific

problems and bring them back alive," said Launius.

He regretted never being able to walk on the moon

The loss of the opportunity to walk on the moon "is my one regret,"

Lovell said in a 1995 interview with The Associated Press.

President Bill Clinton agreed when he awarded Lovell the Congressional

Space Medal of Honor in 1995. "While you may have lost the moon ... you

gained something that is far more important perhaps: the abiding respect

and gratitude of the American people," he said.

Lovell once said that while he was disappointed he never walked on the

moon, "The mission itself and the fact that we triumphed over certain

catastrophe does give me a deep sense of satisfaction."

And Lovell clearly understood why this failed mission afforded him far

more fame than had Apollo 13 accomplished its goal.

"Going to the moon, if everything works right, it's like following a

cookbook. It's not that big a deal," he told the AP in 2004. "If

something goes wrong, that's what separates the men from the boys."

James A. Lovell was born March 25, 1928, in Cleveland. He attended the

University of Wisconsin before transferring to the U.S. Naval Academy,

in Annapolis, Maryland. On the day he graduated in 1952, he and his

wife, Marilyn, were married.

A test pilot at the Navy Test Center in Patuxent River, Maryland, Lovell

was selected as an astronaut by NASA in 1962.

Lovell retired from the Navy and from the space program in 1973, and

went into private business. In 1994, he and Jeff Kluger wrote "Lost

Moon," the story of the Apollo 13 mission and the basis for the film

"Apollo 13." In one of the final scenes, Lovell appeared as a Navy

captain, the rank he actually had.

He and his family ran a now-closed restaurant in suburban Chicago,

Lovell's of Lake Forest.

His wife, Marilynn, died in 2023. Survivors include four children.

In a statement, his family hailed him as their “hero.”

“We will miss his unshakeable optimism, his sense of humor, and the way

he made each of us feel we could do the impossible,” his family said.

“He was truly one of a kind.”

___

Babwin, the principal writer of this obituary, retired from The

Associated Press in 2022. AP Science Writer Seth Borenstein contributed

to this report.

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved |