Trump's attempt to end birthright citizenship would overturn more than a

century of precedent

Send a link to a friend

Send a link to a friend

[January 25, 2025]

By GRAHAM LEE BREWER and JANIE HAR [January 25, 2025]

By GRAHAM LEE BREWER and JANIE HAR

President Donald Trump has said since his first administration that he

wants to end birthright citizenship, a constitutional right for everyone

born in the United States.

This week he issued an executive order that would eliminate it, upending

more than a century of precedent. On Thursday, however, a federal judge

temporarily blocked it after 22 states quickly mounted a legal

challenge.

Over the years the right to citizenship has been won by various

oppressed or marginalized groups after hard-fought legal battles. Here’s

a look at how birthright citizenship has applied to some of those cases

and how the Justice Department is using them today to defend Trump’s

order.

Citizenship for Native Americans

Native Americans were given U.S. citizenship in 1924. The Justice

Department has cited their status as a legal analogy to justify Trump’s

executive order in court.

Arguing that “birth in the United States does not by itself entitle a

person to citizenship, the person must also be ‘subject to the

jurisdiction’ of the United States.” It raised a case from 1884 that

found members of Indian tribes “are not ‘subject to the jurisdiction’ of

the United States and are not constitutionally entitled to Citizenship,”

the department said.

Many scholars take a dim view of the validity of that analogy.

It’s not a good or even new legal argument, said Gerald L. Neuman, a

professor of international, foreign and comparative law at Harvard Law

School. “But it’s got a bigger political movement behind it, and it’s

embedded in a degree of openly expressed xenophobia and prejudice.”

Some say the legal analogy to the citizens of tribal nations plays

directly into that.

“It’s not a valid comparison,” said Leo Chavez, a professor and author

at the University of California, Irvine, who studies international

migration. “It’s using the heat of race to make a political argument

rather than a legal argument.”

“They’re digging into old, archaic Indian law cases, finding the most

racist points they can in order to win,” said Matthew Fletcher, a

professor of law at the University of Michigan and a member of the Grand

Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. “There’s nothing sacred in

the Department of Justice. They’ll do anything they can to win.”

For Spanish and Mexican descendants

In addition to his order on birthright citizenship, Trump has directed

immigration arrests to be expanded to sensitive locations such as

schools. That holds special implications in the border state of New

Mexico, where U.S. citizenship was extended in 1848 to residents of

Mexican and Spanish descent under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which

ended the U.S.-Mexico war.

The state’s 1912 Constitution includes a guarantee saying “children of

Spanish descent in the state of New Mexico shall never be denied the

right and privilege of admission and attendance at public schools … and

they shall never be classed in separate schools, but shall forever enjoy

perfect equality with other children.”

State Attorney General Raúl Torrez has highlighted that provision in

guidance to K-12 schools about how to respond to possible surveillance,

warrants and subpoenas by immigration authorities. The guidance notes

that children cannot be denied access to public education based on

immigration status, citing U.S. Supreme Court precedent.

For enslaved people

The issue of whether enslaved people were eligible for U.S. citizenship

came to the forefront in 1857 when the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 against

Dred Scott, a slave, and his bid to sue for freedom. In their decision,

the court said Black people were not entitled to citizenship and even

claimed they were inferior to white people.

[to top of second column]

|

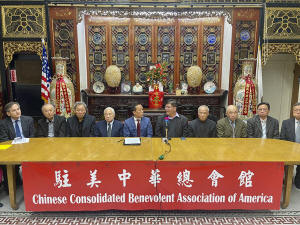

Members of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association of

America sit during a news conference in the Chinatown district of

San Francisco on Friday, Jan. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Haven Daley)

The Dred Scott decision contributed to the start of the Civil War.

With the North's victory over the South, slavery became outlawed.

Among the constitutional protections put in place for formerly

enslaved people, Congress ratified the 14th Amendment in 1868,

guaranteeing citizenship for all, including Black people.

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to

the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of

the State wherein they reside,” the 14th Amendment says. “No State

shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or

immunities of citizens of the United States.”

That effectively nullified the Dred Scott ruling.

For children of immigrants

All children born in the U.S. to immigrants have the right to

citizenship thanks to a Chinese man whose landmark 1898 case went

all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco to parents from China. But

when he tried to return to the U.S. after a visit to that country,

the government denied him reentry under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion

Act, which restricted immigration from China and barred Chinese

immigrants from ever becoming U.S. citizens.

Wong argued that he was a citizen because he was born in the U.S. In

siding with him, the Supreme Court made explicit that the

citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment automatically confers

citizenship to all U.S.-born people regardless of their parents’

status.

In its 6-2 decision, the court said that to deny Wong citizenship

because of his parentage would be “to deny citizenship to thousands

of persons of English, Scotch, Irish, German, or other European

parentage who have always been considered and treated as citizens of

the United States.”

The ruling was a huge relief for the Chinese community as there was

evidence that others were being denied entry, said Bill Ong Hing, a

professor at the University of San Francisco School of Law. They

carried birth certificates and applied for passports proving they

were born in the U.S.

“All the Supreme Court concentrated on was, ‘Are you subject to the

jurisdiction to the United States when you’re born here?’” Hing

said. “And the answer is yes.”

Hing was among Chinese American leaders who criticized Trump’s order

during a news conference Friday at the Chinese Consolidated

Benevolent Association in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The association

helped Wong with his legal case.

Annie Lee, policy director of Chinese for Affirmative Action, said

that Trump's executive order affects all immigrants and children of

immigrants, regardless of legal status.

“When a racist man screams at me to go back to my country, he does

not know or care if I am a U.S. citizen, if I am here on a work visa

or if I am undocumented,” she said. “He looks at me and feels like I

do not belong here. So make no mistake that the white supremacy

which animates this illegal executive order impacts us all.”

___

Associated Press writer Morgan Lee in Santa Fe, New Mexico,

contributed.

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved |