UN says if US funding for HIV programs is not replaced, millions more

will die by 2029

[July 10, 2025]

By MARIA CHENG

LONDON (AP) — Years of American-led investment into AIDS programs has

reduced the number of people killed by the disease to the lowest levels

seen in more than three decades, and provided life-saving medicines for

some of the world’s most vulnerable.

But in the last six months, the sudden withdrawal of U.S. money has

caused a “systemic shock,” U.N. officials warned, adding that if the

funding isn’t replaced, it could lead to more than 4 million

AIDS-related deaths and 6 million more HIV infections by 2029.

“The current wave of funding losses has already destabilized supply

chains, led to the closure of health facilities, left thousands of

health clinics without staff, set back prevention programs, disrupted

HIV testing efforts and forced many community organizations to reduce or

halt their HIV activities,” UNAIDS said in a report released Thursday.

UNAIDS also said that it feared other major donors might also scale back

their support, reversing decades of progress against AIDS worldwide —

and that the strong multilateral cooperation is in jeopardy because of

wars, geopolitical shifts and climate change.

The $4 billion that the United States pledged for the global HIV

response for 2025 disappeared virtually overnight in January when U.S.

President Donald Trump ordered that all foreign aid be suspended and

later moved to shutter the U.S. AID agency.

Andrew Hill, an HIV expert at the University of Liverpool who is not

connected to the United Nations, said that while Trump is entitled to

spend U.S. money as he sees fit, “any responsible government would have

given advance warning so countries could plan,” instead of stranding

patients in Africa when clinics were closed overnight.

The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, was

launched in 2003 by U.S. President George W. Bush, the biggest-ever

commitment by any country focused on a single disease.

UNAIDS called the program a “lifeline” for countries with high HIV

rates, and said that it supported testing for 84.1 million people,

treatment for 20.6 million, among other initiatives. According to data

from Nigeria, PEPFAR also funded 99.9% of the country’s budget for

medicines taken to prevent HIV.

In 2024, there were about 630,000 AIDS-related deaths worldwide, per a

UNAIDS estimate — the figure has remained about the same since 2022

after peaking at about 2 million deaths in 2004.

Even before the U.S. funding cuts, progress against curbing HIV was

uneven. UNAIDS said that half of all new infections are in sub-Saharan

Africa and that more than 50% of all people who need treatment but

aren’t getting it are in Africa and Asia.

[to top of second column]

|

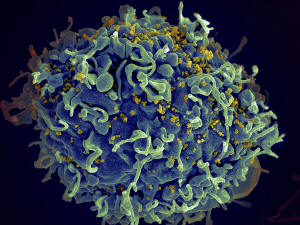

This colorized electron microscope image provided by the U.S.

National Institutes of Health shows a human T cell, in blue, under

attack by HIV, in yellow, the virus that causes AIDS. (Seth Pincus,

Elizabeth Fischer, Austin Athman/National Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases/NIH via AP, File)

Tom Ellman, of the charity Doctors

Without Borders, said that while some poorer countries were now

moving to fund more of their own HIV programs, it would be

impossible to fill the gap left by the U.S.

“There's nothing we can do that will protect these countries from

the sudden, vicious withdrawal of support from the U.S.,” said

Ellman, director of Doctors Without Borders' South Africa Medical

Unit. “Within months of losing treatment, people will start to get

very sick and we risk seeing a massive rise in infection and death.”

Experts also fear another loss: data. The U.S. paid for most HIV

surveillance in African countries, including hospital, patient and

electronic records, all of which has now abruptly ceased, according

to Dr. Chris Beyrer, director of the Global Health Institute at Duke

University.

“Without reliable data about how HIV is spreading, it will be

incredibly hard to stop it,” he said.

The uncertainty comes as a twice-yearly injectable could end HIV, as

studies published last year showed that the drug from pharmaceutical

maker Gilead was 100% effective in preventing the virus.

Last month, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the drug,

called Sunleca — a move that should have been a “threshold moment”

for stopping the AIDS epidemic, said Peter Maybarduk of the advocacy

group Public Citizen.

But activists like Maybarduk said Gilead’s pricing will put it out

of reach of many countries that need it. Gilead has agreed to sell

generic versions of the drug in 120 poor countries with high HIV

rates but has excluded nearly all of Latin America, where rates are

far lower but increasing.

“We could be ending AIDS," Maybarduk said. "Instead, the U.S. is

abandoning the fight.”

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved

|