Appeals court orders new trial for man convicted in 1979 Etan Patz case

[July 22, 2025]

By JENNIFER PELTZ

NEW YORK (AP) — The man convicted in the 1979 killing of 6-year-old Etan

Patz was awarded a new trial Monday as a federal appeals court

overturned the guilty verdict in one of the nation’s most notorious

missing child cases.

Pedro Hernandez has been serving 25 years to life in prison since his

2017 conviction. He had been arrested in 2012 after a decades-long,

haunting search for answers in Etan’s disappearance, which happened on

the first day he was allowed to walk alone to his school bus stop in New

York City.

The appeals court said the trial judge gave a “clearly wrong” and

“manifestly prejudicial” response to a jury note during Hernandez's 2017

trial — his second. His first trial ended in a jury deadlock in 2015.

His lawyers said he was innocent.

The court ordered Hernandez’s release unless the 64-year-old gets a new

trial within “a reasonable period.”

The Manhattan district attorney's office, which prosecuted the case,

said it was reviewing the decision. The trial predated current DA Alvin

Bragg, a Democrat.

Harvey Fishbein, an attorney for Hernandez, declined to comment when

reached Monday by phone.

A message seeking comment was sent to Etan's parents. They spent decades

pursuing an arrest, and then a conviction, in their son's case and

pressing to improve the handling of missing-child cases nationwide.

Etan was among the first missing children pictured on milk cartons. His

case contributed to an era of fear among American families, making

anxious parents more protective of kids who had been allowed to roam and

play unsupervised in their neighborhoods.

The Patzes’ advocacy helped establish a national missing-children

hotline and made it easier for law enforcement agencies to share

information about such cases. The May 25 anniversary of Etan’s

disappearance became National Missing Children’s Day.

“They waited and persevered for 35 years for justice for Etan which

today, sadly, may have been lost,” former Manhattan DA Cyrus Vance Jr.

said after hearing about Monday's reversal. Vance, now in private

practice, had prioritized reexamining the case and oversaw the trials.

Etan was a first grader who always wanted “to do everything that adults

did,” his mother, Julie Patz, told jurors in 2017.

So on the morning of May 25, 1979, she agreed the boy could walk by

himself to the school bus stop a block and a half away. She walked him

downstairs, watched him walk part of the way and never saw him again.

For decades, Etan's parents kept the same apartment and even phone

number in case he might try to reach them.

Etan's case spurred a huge search and an enduring, far-flung

investigation. But no trace of him was ever found. A civil court

declared him dead in 2001.

[to top of second column]

|

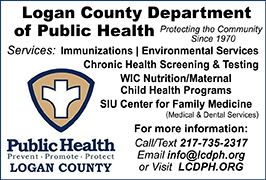

A photograph of Etan Patz hangs on an angel figurine, as part of a

makeshift memorial in the SoHo neighborhood of New York, May 28,

2012. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan, File)

Hernandez was a teenager working at a convenience shop in Etan’s

downtown Manhattan neighborhood when the boy vanished. Police met him

while canvassing the area but didn't suspect him until they got a 2012

tip that he’d made remarks years earlier about having killed a child in

New York, not mentioning Etan's name.

Hernandez then told police he'd lured Etan into the store’s basement by

promising the boy a soda, then choked him because “something just took

over me.” He said he put Etan, still alive, in a box and left it with

curbside trash.

Hernandez’s lawyers said his confession was false, spurred by a mental

illness that makes him confuse reality with imagination. He also has a

very low IQ.

His daughter testified that he talked about seeing visions of angels and

demons and once watered a dead tree branch, believing it would grow.

Prosecutors suggested Hernandez faked or exaggerated his symptoms.

The defense pointed to another suspect, a convicted child molester who

made incriminating statements years ago about Etan but denied killing

him and later insisted he wasn’t involved in the boy’s disappearance. He

was never charged.

The trials happened in a New York state court. Etan's appeal eventually

wound into federal court and revolved around Hernandez' police

interrogation in 2012.

Police questioned Hernandez for seven hours — and they said he confessed

— before they read him his rights and started recording. Hernandez then

repeated his admission on tape, at least twice.

During nine days of deliberations, jurors sent repeated queries about

those statements. The last inquiry asked whether they had to disregard

the two recorded confessions if they concluded that the first one was

invalid.

The judge said no. The appeals court said the jury should have gotten a

more thorough explanation of its options, which could have included

disregarding all of the confessions.

___

Associated Press writers Larry Neumeister in New York and Eric Tucker in

Washington contributed.

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved

|