A Border Patrol agent died in 2009. His widow is still fighting a

backlogged US program for benefits

[June 14, 2025]

By RYAN J. FOLEY

When her husband died after a grueling U.S. Border Patrol training

program for new agents, Lisa Afolayan applied for the federal benefits

promised to families of first responders whose lives are cut short in

the line of duty.

Sixteen years later, Afolayan and her two daughters haven't seen a

penny, and program officials are defending their decisions to deny them

compensation. She calls it a nightmare that too many grieving families

experience.

“It just makes me so mad that we are having to fight this so hard,” said

Afolayan, whose husband, Nate, had been hired to guard the U.S. border

with Mexico in southern California. “It takes a toll emotionally, and I

don’t think they care. To them, it’s just a business. They’re just

pushing paper.”

Afolayan's case is part of a backlog of claims plaguing the fast-growing

Public Safety Officers' Benefits Program. Hundreds of families of

deceased and disabled officers are waiting years to learn whether they

qualify for the life-changing payments, and more are ultimately being

denied, an Associated Press analysis of program data found.

The program is falling far short of its goal of deciding claims within

one year. Nearly 900 have been pending for longer than that, triple the

number from five years earlier, in a backlog that includes cases from

nearly every state, according to AP’s review, which was based on program

data through late April.

More than 120 of those claims have been in limbo for at least five

years, and roughly a dozen have languished for a decade.

“That is just outrageous that the person has to wait that long,” said

Charlie Lauer, the program's general counsel in the 1980s. “Those poor

families.”

Justice Department officials, who oversee the program, acknowledge the

backlog. They say they're managing a surge in claims — which have more

than doubled in the last five years — while making complicated decisions

about whether cases meet legal criteria.

In a statement, they said “claims involving complex medical and

causation issues, voluminous evidence and conflicting medical opinions

take longer to determine, as do claims in various stages of appeal.” It

acknowledged a few cases "continue through the process over ten years.”

Program officials wouldn’t comment on Afolayan’s case. Federal lawyers

are asking an appeals court for a second time to uphold their denials,

which blame Nate’s heat- and exertion-related death on a genetic

condition shared by millions of mostly Black U.S. citizens.

Supporters say Lisa Afolayan's resilience in pursuing the claim has been

remarkable, and grown in significance as training-related deaths like

Nate’s have risen.

“Your death must fit in their box, or your family’s not going to be

taken care of,” said Afolayan, of suburban Dallas.

Their daughter, Natalee, was 3 when her father died. She recently

completed her first year at the University of Texas, without the help of

the higher education benefits the program provides.

The officers' benefits program is decades old and has paid billions

Congress created the Public Safety Officers’ Benefits program in 1976,

providing a one-time $50,000 payout as a guarantee for those whose loved

ones die in the line of duty.

The benefit was later set to adjust with inflation; today it pays

$448,575. The program has awarded more than $2.4 billion.

Early on, claims were often adjudicated within weeks. But the complexity

increased in 1990, when Congress extended the program to some disabled

officers. A 1998 law added educational benefits for spouses and

children.

Since 2020, Congress has passed three laws expanding eligibility — to

officers who died after contracting COVID-19, first responders who died

or were disabled in rescue and cleanup operations from the September

2001 attacks, and some who die by suicide.

Today, the program sees 1,200 claims annually, up from 500 in 2019.

The wait time for decisions and rate of denials have risen alongside the

caseload. Roughly one of every three death and disability claims were

rejected over the last year.

U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz and other Republicans recently introduced legislation

to require the program to make determinations within 270 days,

expressing outrage over the case of an officer disabled in a mass

shooting who's waited years for a ruling. Similar legislation died last

year.

One group representing families, Concerns of Police Survivors, has

expressed no such concerns about the program's management. The

Missouri-based nonprofit recently received a $6 million grant to

continue its longstanding partnership with the Justice Department to

serve deceased officers’ relatives — including providing counseling,

hosting memorial events and assisting with claims.

“We are very appreciative of the PSOB and their work with survivor

benefits,” spokesperson Sara Slone said. “Not all line-of-duty deaths

are the same and therefore processing times will differ.”

Nate Afolayan dreamed of serving his adopted country

Born in Nigeria, Nate Afolayan moved to California with relatives at age

11. He became a U.S. citizen and graduated from California State

University a decade later.

Lisa met Nate while they worked together at a juvenile probation office.

They talked, went out for lunch and felt sparks.

“The next thing you know, we were married with two kids,” she said.

He decided to pursue a career in law enforcement once their second

daughter was born. Lisa supported him, though she understood the danger.

He spent a year working out while applying for jobs and was thrilled

when the Border Patrol declared him medically fit; sent him to Artesia,

New Mexico, for training; and swore him in.

Nate loved his 10 weeks at the academy, Lisa said, despite needing

medical treatment several times — he was shot with pepper spray in the

face and became dizzy during a water-based drill.

His classmates found him to be a natural leader in elite shape and chose

him to speak at graduation, they recalled in interviews with

investigators.

He prepared a speech with the line, “We are all warriors that stand up

and fight for what's right, just and lawful."

But on April 30, 2009 — days before the ceremony — a Border Patrol

official called Lisa. Nate, 29, had fainted after his final training run

and was hospitalized.

It was dusty and 88 degrees in the high desert that afternoon. Agents

had to complete the 1.5-mile run in 13 minutes, at an altitude of 3,400

feet. Nate had warned classmates it was too hot to wear their black

academy shirts, but they voted to do so anyway, records show.

Nate, 29, finished in just over 11 minutes but then struggled to breathe

and collapsed.

Now Nate was being airlifted to a Lubbock, Texas, hospital for advanced

treatment. Lisa booked a last-minute flight, arriving the next day.

[to top of second column]

|

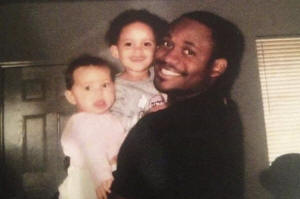

This 2008 photo provided by Lisa Afolayan shows Nate Afolayan with

his daughters, Natalee and Lea, at their home in San Jacinto, Calif.

(Lisa Afolayan via AP)

A doctor told her Nate’s organs had shut down and they couldn't save

his life. The hospital needed permission to end life-saving efforts.

One nurse delivered chest compressions; another held Lisa tightly as

she yelled: “That’s it! I can’t take it anymore!”

Lisa became a single mother. The girls were 3 and 1.

Her only comfort, she said, was knowing Nate died living his dream —

serving his adopted country.

Sickle cell trait was cited in this benefit denial

When she first applied for benefits, Lisa included the death

certificate that listed heat illness as the cause of Nate’s death.

The aid could help her family. She'd been studying to become a nurse

but had to abandon that plan. She relied on Social Security

survivors’ benefits and workers’ compensation while working at gyms

as a trainer or receptionist and dabbling in real estate.

The program had paid benefits for a handful of similar training

deaths, dating to a Massachusetts officer who suffered heat stroke

and dehydration in 1988. But program staff wanted another opinion on

Nate’s death. They turned to outside forensic pathologist Dr.

Stephen Cina.

Cina concluded the autopsy overlooked the “most significant factor”:

Nate carried sickle cell trait, a condition that's usually benign

but has been linked to rare exertion-related deaths in military,

sports and law enforcement training.

Cina opined that exercising in a hot climate at high altitude

triggered a crisis in which Nate’s red blood cells became misshapen,

depriving his body of oxygen. Cina, who stopped consulting for the

benefits program in 2020 after hundreds of case reviews, declined to

comment.

Nate learned he had the condition, carried by up to 3 million U.S.

Black citizens, after a blood test following his second daughter’s

birth. The former high school basketball player had never

experienced any problems.

A Border Patrol spokesperson declined to say whether academy leaders

knew of the condition, which experts say can be managed with

precautions such as staying hydrated, avoiding workouts in extreme

temperatures and altitudes, and taking rest breaks.

Under the benefit program’s rules, Afolayan’s death would need to be

“the direct and proximate result” of an injury he suffered on duty

to qualify. It couldn't be the result of ordinary physical strain.

The program in 2012 rejected the claim, saying the hot, dry, high

climate was one factor, but not the most important.

It had been more than two years since Lisa Afolayan applied and

three since Nate's death.

Lisa Afolayan's appeal was not common

Most rejected applicants don’t exercise their option to appeal to an

independent hearing officer, saying they can't afford attorneys or

want to get on with their lives.

But Lisa Afolayan appealed with help from a border patrol union. A

one-day hearing was held in late 2012. The hearing officer denied

her claim more than a year later, saying the “perfect storm” of

factors causing the death didn't include a qualifying injury.

Lisa and her daughters moved from California to Texas. They visited

the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington, where

they saw Nate's name.

Four years passed without an update on the claim. Lisa learned the

union had failed to exercise its final appeal, to the program

director, due to an oversight. The union didn't respond to AP emails

seeking comment.

Then she met Suzie Sawyer, founder and retired executive director of

Concerns of Police Survivors. Sawyer had recently helped win a long

battle to obtain benefits in the death of another federal agent

who’d collapsed during training.

“I said, ‘Lisa, this could be the fight of your life, and it could

take forever,'" Sawyer recalled. "'Are you willing to do it?’ She

goes, ‘hell yes.’”

The two persuaded the program to hear the appeal even though the

deadline had passed. They introduced a list of similar claims that

had been granted and new evidence: A Tennessee medical examiner

concluded the hot, dry environment and altitude were key factors

causing Nate’s organ-system failure.

But the program was unmoved. The acting Bureau of Justice Assistance

director upheld the denial in 2020.

Such rulings usually aren’t public, but Lisa fumed as she learned

through contacts about some whose deaths qualified, including a

trooper who had an allergic reaction to a bee sting, an intoxicated

FBI agent who crashed his car, and another officer with sickle cell

trait who died after a training run on a hot day.

Today, an appeal is still pending

In 2022, Lisa thought she might have finally prevailed when a

federal appeals court ordered the program to take another look at

her application.

A three-judge panel said the program erred by failing to consider

whether the heat, humidity and altitude during the run were “the

type of unusual or out-of-the-ordinary climatic conditions that

would qualify.”

The judges also said it may have been illegal to rely on sickle cell

trait for the denial under a federal law prohibiting employers from

discrimination on the basis of genetic information.

It was great timing: The girls were in high school and could use the

monthly benefit of $1,530 to help pay for college. The family’s

Social Security and workers’ compensation benefits would end soon.

But the program was in no hurry. Nearly two years passed without a

ruling despite inquiries from Afolayan and her lawyer.

The Bureau of Justice Assistance director upheld the denial in

February 2024, ruling that the climate on that day 15 years earlier

wasn’t “unusually adverse.” The decision concluded the Genetic

Information Nondiscrimination Act didn't apply since the program

wasn’t Afolayan’s employer.

Arnold & Porter, a Washington law firm now representing Afolayan pro

bono, has appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

Her attorney John Elwood said the program has gotten bogged down in

minutiae while losing sight of the bigger picture: that an officer

died during mandatory training. He said government lawyers are

fighting him just as hard, “if not harder,” than on any other case

he’s handled.

Months after filing their briefs, oral arguments haven't been set.

“This has been my life for 16 years,” Lisa Afolayan said. “Sometimes

I just chuckle and keep moving because what else am I going to do?”

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved |