NFL widows struggled to care for former players with CTE. They say a new

study minimizes their pain

[June 20, 2025]

By JIMMY GOLEN

BOSTON (AP) — Dozens of widows and other caregivers for former NFL

players diagnosed with CTE say a published study is insulting and

dismissive of their experience living with the degenerative brain

disease that has been linked to concussions and other repeated head

trauma common in contact sports like football.

An open letter signed by the players’ wives, siblings and children says

the study published in the May 6 issue of Frontiers in Psychology

suggests their struggles caring for loved ones was due to “media hype”

about chronic traumatic encephalopathy, rather than the disease itself.

The implication that “caregiver concerns are ‘inevitable’ due to

‘publicity’ is callous, patronizing, and offensive,” they said.

“The burden we experienced did not happen because we are women unable to

differentiate between our lived experience and stories from TV or

newspaper reports,” they wrote in the letter. “Our loved ones were

giants in life, CTE robbed them of their futures, and robbed us of our

futures with them. Please don’t also rob us of our dignity.”

The pushback was led by Dr. Eleanor Perfetto, herself a medical

researcher and the widow of former Steelers and Chargers end Ralph

Wenzel, who developed dementia and paranoia and lost his ability to

speak, walk and eat. He was first diagnosed with cognitive impairment in

1999 — six years before Pittsburgh center Mike Webster’s CTE diagnosis

brought the disease into the mainstream media.

“My own experience, it just gave a name to what I witnessed every day.

It didn’t put it in my head,” Perfetto said in an interview with The

Associated Press. “It gave it a name. It didn't change the symptoms.”

The study published last month asked 172 caregivers for current and

former professional football players “whether they believed their

partner had ‘CTE.’” Noting that all of the respondents were women,

Perfetto questioned why their experiences would be minimized.

“Women run into that every day,” she said. “I don't think that's the

only factor. I think the motivation is to make it seem like this isn’t a

real issue. It’s not a real disease. It’s something that people glommed

on to because they heard about it in the media."

Hopes for study ‘quickly turned to disappointment’

The letter was posted online on Monday under the headline, “NFL

Caregivers to Harvard Football Player Health Study: Stop Insulting Us!”

It had more than 30 signatures, including family of Hall of Famers Nick

Buoniconti and Louis Creekmur.

It praises the study for examining the fallout on loved ones who

weathered the violent mood swings, dementia and depression that can come

with the disease. The letter says the study gets it wrong by including

what it considers unsupported speculation, such as: “Despite being an

autopsy-based diagnosis, mainstream media presentations and high-profile

cases related to those diagnosed postmortem with CTE may have raised

concerns among living players about CTE."

The letter said these are "insulting conclusions that were not backed by

study evidence.”

“Rather than exploring the lived experiences of partners of former

athletes, they instead implied the partners’ anxiety was caused by

watching the news ... as if the media is to blame for the severe brain

atrophy caused by CTE in our loved ones," they wrote.

Study authors Rachel Grashow and Alicia Whittington said in a statement

provided to the AP that the goal of their research is “to support NFL

families, especially those caring for affected players or grieving for

lost loved ones.”

“We regret if any of our work suggested otherwise,” they said. “Our

intent was not to minimize CTE — a disease that is far too real — but to

point out that heightened attention to this condition can intensify

existing concerns, and that symptoms attributed to CTE may, in some

cases, stem from other treatable conditions that also deserve

recognition and care.”

[to top of second column]

|

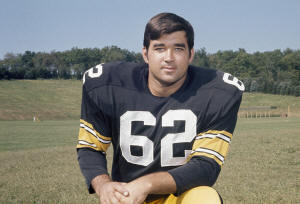

Ralph Wenzel, (62) football player for the Pittsburgh Steelers,

1970. (AP Photo, file)

But Perfetto feared the study was

part of a trend to downplay or even deny the risks of playing

football. After years of denials, the NFL acknowledged in 2016 a

link between football and CTE and eventually agreed to a settlement

covering 20,000 retired players that provided up to $4 million for

those who died with the disease. (Because it requires an examination

of the brain tissue, CTE currently can only be diagnosed

posthumously.)

“Why would a researcher jump to ‘the media’ when trying to draw

conclusions out of their data, when they didn’t collect any

information about the media,” Perfetto told the AP. "To me, as a

researcher, you draw the implications from the results and you try

to think of, practically, ‘Why you come to these conclusions? Why

would you find these results?’ Well, how convenient is it to say

that it was the media, and it takes the NFL off the hook?”

‘By players, for players’

The caregivers study is under the umbrella of the Football Players

Health Study at Harvard University, a multifaceted effort "working

on prevention, diagnostics, and treatment strategies for the most

common and severe conditions affecting professional football

players.” Although it is funded by the NFL Players Association,

neither the union nor the league has any influence on the results or

conclusions, the website says.

“The Football Players Health Study does not receive funding from the

NFL and does not share any data with the NFL,” a spokesperson said.

Previous research — involving a total of more than 4,700 ex-players

— is on topics ranging from sleep problems to arthritis. But much of

it has focused on brain injuries and CTE, which has been linked to

contact sports, military combat and other activities that can

involve repetitive head trauma.

When he died with advanced CTE in 2012 at age 69, Wenzel could no

longer recognize Perfetto and needed help with everyday tasks like

getting dressed or getting out of bed — an added problem because he

was a foot taller and 100 pounds heavier than she is. "When he died,

his brain had atrophied to 910 grams, about the size of the brain of

a 1-year-old child,” the letter said.

Former Auburn and San Diego Chargers running back Lionel “Little

Train” James, who set the NFL record for all-purpose yards in 1985,

was diagnosed with dementia at 55 and CTE after he died at 59.

“Treatable conditions were not the reason Lionel went from being a

loving husband and father to someone so easily agitated that his

wife and children had to regularly restrain him from becoming

violent after dodging thrown objects,” the letter said. “They were

not likely to be the driving force behind his treatment-resistant

depression, which contributed to alcoholism, multiple stays in

alcohol rehabilitation treatment centers, arrests, suicidal

ideation, and ultimately, his commitment to a mental institution.”

Kesha James told the AP that she would disable the car to keep her

husband from driving drunk. She said she had never spoken of her

struggles but chose to tell her story now to remove the stigma

associated with the players' late-in-life behavior — and the

real-life struggles of their caregivers.

“I have videos that people probably would not believe,” James said.

“And I’ll be honest with you: It is nothing that I’m proud of. For

the last three years I’ve been embarrassed. I’m just going public

now because I do want to help bring awareness to this — without

bringing any shame to me and my kids — but just raise the awareness

so that no other family can experience what I did."

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved |