South Africa's giant playwright Athol Fugard, whose searing works

challenged apartheid, dies aged 92

[March 10, 2025]

By MARK KENNEDY and GERALD IMRAY

CAPE TOWN, South Africa (AP) — Athol Fugard, South Africa's foremost

dramatist who explored the pervasiveness of apartheid in such searing

works as "The Blood Knot" and "’Master Harold’... and the Boys," has

died. He was 92.

The South African government confirmed Fugard's death and said the

country “has lost one of its greatest literary and theatrical icons,

whose work shaped the cultural and social landscape of our nation.”

Six of Fugard's plays landed on Broadway, including two productions of

“’Master Harold’... and the Boys,” in 1982 and 2003.

Because Fugard’s best-known plays center on the suffering caused by the

apartheid policies of South Africa's white-minority government, some

among Fugard's audience abroad were surprised to find he was white

himself.

“’Master Harold’... and the Boys” is a Tony Award-nominated work set in

a South African tea shop in 1950. It centers on the relationship between

the son of the white owner and two Black servants who have served as

surrogate parents. One rainy afternoon, the bonds between the characters

are stressed to breaking point when the young man begins to abuse his

elders.

“In plain words, just get on with your job," the boy tells one servant.

"My mother is right. She’s always warning me about allowing you to get

too familiar. Well, this time you’ve gone too far. It’s going to stop

right now. You’re only a servant in here, and don’t forget it.”

When it opened in Johannesburg in 1983 — at the height of apartheid — in

the audience was anti-apartheid activist Desmond Tutu. "I thought it was

something for which you don't applaud. The first response is weeping,"

Tutu, who died in 2021, said after the final curtain. “It's saying

something we know, that we've said so often about what this country does

to human relations.”

"The Road to Mecca," with its three white characters, touches on

apartheid of a different sort. It concerns an adventurous artist named

Miss Helen, at odds with and cut off from the rigid and unyielding

Afrikaners around her. It's her eccentric artwork that severs her from

society and makes her the subject of a fight for control.

A production opened in San Francisco in 2023, prompting the San

Francisco Chronicle's theater critic to note that “its central concern —

how to deal with people who are aging and alone — feels ripe for our own

moment of declining birth rates and increasing life expectancy amid a

fraying social safety net.”

Fugard once told an interviewer that the best theater in Africa would

come from South Africa because the country's "daily tally of injustice

and brutality has forced a maturity of thinking and feeling and an

awareness of basic values I do not find equaled anywhere in Africa."

Fugard was born in Middleburg in the semiarid Karoo on June 11, 1932.

His father was an English-Irish man whose joy was playing jazz piano.

His mother was Afrikaans, descended from South Africa's early

Dutch-German settlers, and earned the family's income by running a

store.

Fugard said his first trip into Johannesburg's Black enclave of

Sophiatown — since destroyed and replaced with a white residential area

— was "a definitive event of my life. I first went in there as the

result of an accident. I suddenly encountered township life."

[to top of second column]

|

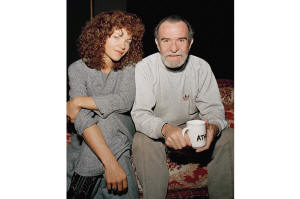

Actress Amy Irving sits with actor-director-playwright Athol Fugard

during rehearsals of the play "The Road to Mecca" on Feb. 29, 1988

in New York. (AP Photo/Mario Cabrera, File)

This ignited Fugard's longstanding

urge to write. He left the University of Cape Town just before he

would have graduated in philosophy because "I had a feeling that if

I stayed I might be stuck into academia."

Fugard became a target for the apartheid government and his passport

was taken away for four years after he directed a Black theater

workshop, "The Serpent Players." Five workshop members were

imprisoned on Robben Island, where South Africa kept political

prisoners, including Nelson Mandela. Fugard and his family endured

years of government surveillance; their mail was opened, their

phones tapped, and their home subjected to midnight police searches.

He hitchhiked through Africa in 1953 with South African poet Perseus

Adams, and ended up working as a sailor, the only white seaman on

his ship. Fugard's theater experience was confined to acting in a

school play until 1956, when he married actor Sheila Meiring and

began concentrating on stage writing. He and Meiring later divorced.

He married second wife Paula Fourie in 2016.

He took a job in 1958 as a clerk with a Johannesburg Native

Commissioner's Court, where Black people who broke racial laws were

sentenced, “one every two minutes.”

"We were absolutely broke. I needed a job and I needed information

on the pass system," Fugard said. His job included witnessing the

caning of lawbreakers. “It was the darkest period of my life.”

He got some satisfaction in putting a small wrench in the works, by

"shuffling up the charge sheets," delaying proceedings enough for

friends of the Black detainees to get them lawyers.

Fugard wrote, directed and acted in his early productions. On the

eve of the opening of "A Lesson From Aloes," at Johannesburg's

Market Theater, Fugard dismissed one of the three performers and

took the role himself.

Later in life, Fugard taught acting, directing and playwriting at

the University of California, San Diego. In 2006, the film “Tsotsi,”

based on his 1961 novel, won international awards, including the

Oscar for foreign language film. He won a Tony Award for lifetime

achievement in 2011.

More recent plays include “The Train Driver" (2010) and “The Bird

Watchers” (2011), which both premiered at the Fugard Theatre in Cape

Town. As an actor, he appeared in the films “The Killing Fields” and

“Gandhi.” In 2014, Fugard returned to the stage as an actor for the

first time in 15 years in his own play, “Shadow of the Hummingbird,”

at the Long Wharf in New Haven, Connecticut.

——

Kennedy reported from New York.

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved

|