HIV soars after a deadly war in Ethiopia's Tigray. Trump's aid cuts

aren't helping

[March 26, 2025]

By FRED HARTER

SHIRE, Ethiopia (AP) — The woman survived two brutal attacks in the

dying days of the war in Ethiopia’s Tigray region. First, she said, she

was dragged to a military encampment and gang-raped by Eritrean soldiers

who held dozens of other women. Two days later, she was raped again by a

group of militiamen.

Her attackers broke her collarbone and her wrist. They also infected her

with HIV. More than two years later, she can sometimes buy

antiretroviral drugs by selling part of the wheat she gets as a

displaced person, but it's not enough.

“I am strong, but my disease is getting worse and worse,” the woman told

The Associated Press at a clinic in Shire, a town in northwestern Tigray.

The AP typically does not identify people who are victims of sexual

abuse.

Tigray was once considered a model in the fight against HIV. Years of

awareness-raising efforts had brought the region's HIV prevalence rate

to 1.4%, one of the lowest in Ethiopia.

Then, in 2020, war began between Ethiopia's government, backed by

neighboring Eritrea, and Tigray fighters.

Sexual violence was widespread in the two-year conflict, which also had

mass killings, hunger and disease. As many as 10% of women and girls

aged between 15 and 49 in the region of 6 million people were subject to

sexual abuse, mostly rape and gang rape, according to a study published

by BMJ Global Health in 2023.

At the same time, Tigray’s health system was systematically looted and

destroyed, leaving only 17% of health centers functional, according to

another study in the same journal.

As a result, 90% of sexual violence survivors did not get timely medical

support.

The woman told the AP she did not get medication for nearly eight

months. The window for receiving prophylaxis to prevent HIV is 72 hours.

Today the HIV prevalence rate in Tigray is 3%, more than double the

prewar average, according to local health authorities and the United

Nations. The rate among the region’s roughly 1 million displaced people

is 5.5%.

Among sexual violence survivors, it is 8.6%.

“It was a horrific conflict,” said Amanuel Haile, the head of Tigray’s

health bureau. “War was everywhere. Crops failed. Rape was widespread.

Hospitals were vandalized. Drugs were interrupted.”

The “complete breakdown” of Tigray’s health services also meant existing

HIV patients did not receive antiretrovirals during the war, increasing

their risk of transmitting the virus through pregnancy or unprotected

sex, Amanuel said.

Few condoms were available during the war, which saw Tigray cut off from

the rest of Ethiopia. Today, some destitute displaced people engage in

sex work to survive, another factor that health workers believe is

contributing to the spike in HIV cases.

The Trump administration’s decision to kill 83% of U.S. Agency for

International Development programs globally is worsening the situation.

[to top of second column]

|

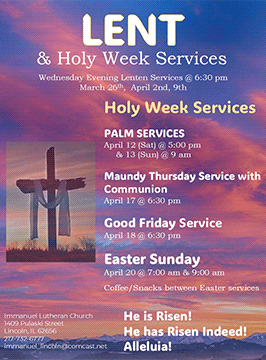

A woman who says she was dragged to a military encampment and gang

raped by Eritrean soldiers and militiamen over a period of two days,

pose for a photo in Shire in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia,

Oct. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Fred Harter)

Ethiopia has already laid off 5,000

health workers who were hired with U.S. funds to combat HIV.

Meanwhile, charities helping HIV patients receive treatment have

received stop-work orders.

They include the Organization for Social Services, Health and

Development, a national agency whose Tigray branch was testing

people for HIV and giving HIV patients food and financial support.

“Since the end of the war, things were slowly improving,” said Yirga

Gebregziabher, OSSHD’s manager in Tigray. “Now so many services have

stopped again.”

Like the rest of Ethiopia, Tigray is also grappling with sharp rises

in other infectious diseases because of the effects of conflict,

climate change and funding cuts.

Nationally, malaria cases have soared from 900,000 in 2019 to over

10 million last year. The war interrupted efforts to distribute nets

and spray high-risk areas with insecticides to prevent the

mosquito-borne disease. Measles rose from 1,941 cases in 2021 to

28,129 in 2024. Cholera and tuberculosis are also making comebacks.

Health workers say Tigray is particularly ill-equipped to deal with

these outbreaks. It has few ambulances after most of its emergency

vehicles were destroyed in the war. Some doctors have not been paid

for 17 months. And its biggest health facility, Ayder Referral

Hospital, only has 50% of the drugs it needs.

“These outbreaks are extremely damaging,” said Amanuel with the

regional health bureau. “We have a lot to rebuild, and outbreaks

take up whatever meager resources we have.”

Meanwhile millions in Tigray still rely on humanitarian aid and 18%

of children are malnourished, leaving them vulnerable to diseases.

“We are attempting to rebuild, but still in a state of crisis,” said

Abraha Gebreegziabher, the clinical director of Ayder Referral

Hospital.

Abraha’s institution is grappling with severe budget cuts and debts

that mean it cannot afford basic drugs or items like tubes and

syringes. The hospital requires patients to pay for services that

were previously free.

Crucially, the war also destroyed Tigray’s system of community-based

health insurance, a low-cost program that underpinned the region’s

health system.

Restarting this scheme is the health bureau’s top priority, Amanuel

said.

But Tigray's political leaders have become locked in a power

struggle that escalated this month when a faction took over several

government offices. That threatens to deter donors who have memories

of the recent war.

___

Associated Press writer Samuel Getachew in Mekele, Ethiopia,

contributed to this report.

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved |