Trump’s clash with the courts raises prospect of showdown over

separation of powers

[May 19, 2025]

By NICHOLAS RICCARDI

DENVER (AP) — Tucked deep in the thousand-plus pages of the

multitrillion-dollar budget bill making its way through the

Republican-controlled U.S. House is a paragraph curtailing a court’s

greatest tool for forcing the government to obey its rulings: the power

to enforce contempt findings.

It’s unclear whether the bill can pass the House in its current form —

it failed in a committee vote Friday — whether the U.S. Senate would

preserve the contempt provision or whether courts would uphold it. But

the fact that GOP lawmakers are including it shows how much those in

power in the nation's capital are thinking about the consequences of

defying judges as the battle between the Trump administration and the

courts escalates.

Republican President Donald Trump raised the stakes again Friday when he

attacked the U.S. Supreme Court for its ruling barring his

administration from quickly resuming deportations under an 18th-century

wartime law: “THE SUPREME COURT WON’T ALLOW US TO GET CRIMINALS OUT OF

OUR COUNTRY!” Trump posted on his social media network, Truth Social.

Trump vs. the district courts

The most intense skirmishes have come in the lower courts.

One federal judge has found that members of the administration may be

liable for contempt after ignoring his order to turn around planes

deporting people under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. Trump's

administration has scoffed at another judge’s ruling that it

“facilitate” the return of a man wrongly deported to El Salvador, even

though the Supreme Court upheld that decision.

In other cases, the administration has removed immigrants against court

orders or had judges find that the administration is not complying with

their directives. Dan Bongino, now Trump's deputy director of the FBI,

called on the president to “ignore” a judge’s order in one of Bongino's

final appearances on his talk radio show in February.

“Who’s going to arrest him? The marshals?” Bongino asked, naming the

agency that enforces federal judges’ criminal contempt orders. “You guys

know who the U.S. Marshals work for? Department of Justice.”

Administration walking ‘close to the line’

The rhetoric obscures the fact that the administration has complied with

the vast majority of court rulings against it, many of them related to

Trump's executive orders. Trump has said multiple times he will comply

with orders, even as he attacks by name judges who rule against him.

While skirmishes over whether the federal government is complying with

court orders are not unusual, it's the intensity of the Trump

administration's pushback that is, legal experts say.

“It seems to me they are walking as close to the line as they can, and

even stepping over it, in an effort to see how much they can get away

with,” said Steve Vladeck, a Georgetown law professor. “It’s what you

would expect from a very clever and mischievous child.”

Mike Davis, whose Article III Project pushes for pro-Trump judicial

appointments, predicted that Trump will prevail over what he sees as

hostile judges.

“The more they do this, the more it's going to anger the American

people, and the chief justice is going to follow the politics on this

like he always does,” Davis said.

The clash was the subtext of an unusual Supreme Court session Thursday,

the day before the ruling that angered the president. His administration

was seeking to stop lower courts from issuing nationwide injunctions

barring its initiatives. Previous administrations have also chafed

against national orders, and multiple Supreme Court justices have

expressed concern that they are overused.

Still, at one point, Justice Amy Coney Barrett pressed Solicitor General

D. John Sauer over his assertion that the administration would not

necessarily obey a ruling from an appeals court.

“Really?” asked Barrett, who was nominated to the court by Trump.

Sauer contended that was standard Department of Justice policy and he

assured the nation’s highest court the administration would honor its

rulings.

‘He's NOT coming back’

Some justices have expressed alarm about whether the administration

respects the rule of law.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown-Jackson, both nominated by

Democratic presidents, have warned about government disobedience of

court orders and threats toward judges. Chief Justice John Roberts,

nominated by a Republican president, George W. Bush, issued a statement

condemning Trump's push to impeach James E. Boasberg, the federal judge

who found probable cause that the administration committed contempt by

ignoring his order on deportations.

[to top of second column]

|

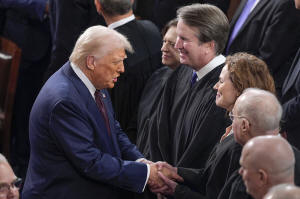

President Donald Trump, left, greets justices of the Supreme Court,

from left, Elena Kagan, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett,

before addressing a joint session of Congress at the Capitol in

Washington, March 4, 2025. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

Even after the Supreme Court upheld a Maryland judge’s ruling

directing the administration to “facilitate” the return of Kilmar

Abrego Garcia, the White House account on X said in a post: “he's

NOT coming back.”

Legal experts said the Abrego Garcia case may be heading toward

contempt.

U.S. District Court Judge Paula Xinis has complained of “bad faith”

from the administration as she orders reports on what, if anything,

it’s doing to comply with her order. But contempt processes are slow

and deliberative, and, when the government’s involved, there’s

usually a resolution before penalties kick in.

What is contempt of court?

Courts can hold parties to civil litigation or criminal cases in

contempt for disobeying their orders. The penalty can take the form

of fines or other civil punishments, or even prosecution and jail

time, if pursued criminally.

The provision in the Republican budget bill would prohibit courts

from enforcing contempt citations for violations of injunctions or

temporary restraining orders — the two main types of rulings used to

rein in the Trump administration — unless the plaintiffs have paid a

bond. That rarely happens when someone sues the government.

In an extensive review of contempt cases involving the government,

Yale law professor Nick Parrillo identified only 67 where someone

was ultimately found in contempt. That was out of more than 650

cases where contempt was considered against the government.

Appellate courts reliably overturned the penalties.

But the higher courts always left open the possibility that the next

contempt penalties could stick.

“The courts, for their part, don’t want to find out how far their

authority goes,” said David Noll, a Rutgers law professor, “and the

executive doesn’t really want to undermine the legal order because

the economy and their ability to just get stuff done depends on the

law.”

‘It’s truly uncharted territory'

Legal experts are gaming out whether judges could appoint

independent prosecutors or be forced to rely on Trump’s Department

of Justice. Then there’s the question of whether U.S. marshals would

arrest anyone convicted of the offense.

“If you get to the point of asking the marshals to arrest a

contemnor, it’s truly uncharted territory,” Noll said.

There’s a second form of contempt that could not be blocked by the

Department of Justice –- civil contempt, leading to fines. This may

be a more potent tool for judges because it doesn’t rely on federal

prosecution and cannot be expunged with a presidential pardon, said

Justin Levitt, a department official in the Obama administration who

also advised Democratic President Joe Biden.

“Should the courts want, they have the tools to make individuals who

plan on defying the courts miserable,” Levitt said, noting that

lawyers representing the administration and those taking specific

actions to violate orders would be the most at risk.

There are other deterrents courts have outside of contempt.

Judges can stop treating the Justice Department like a trustworthy

agency, making it harder for the government to win cases. There were

indications in Friday's Supreme Court order that the majority didn't

trust the administration's handling of the deportations. And defying

courts is deeply unpopular: A recent Pew Research Center poll found

that about 8 in 10 Americans say that if a federal court rules a

Trump administration action is illegal, the government has to follow

the court’s decision and stop its action.

That's part of the reason the broader picture might not be as

dramatic as the fights over a few of the immigration cases, said

Vladeck, the Georgetown professor.

“In the majority of these cases, the courts are successfully

restraining the executive branch and the executive branch is abiding

by their rulings,” he said.

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved

|