Lifelong drugs for autoimmune diseases don't work well. Now scientists

are trying something new

[November 14, 2025]

By LAURAN NEERGAARD

Scientists are trying a revolutionary new approach to treat rheumatoid

arthritis, multiple sclerosis, lupus and other devastating autoimmune

diseases — by reprogramming patients’ out-of-whack immune systems.

When your body’s immune cells attack you instead of protecting you,

today’s treatments tamp down the friendly fire but they don’t fix what’s

causing it. Patients face a lifetime of pricey pills, shots or infusions

with some serious side effects — and too often the drugs aren’t enough

to keep their disease in check.

“We’re entering a new era,” said Dr. Maximilian Konig, a rheumatologist

at Johns Hopkins University who’s studying some of the possible new

treatments. They offer “the chance to control disease in a way we’ve

never seen before.”

How? Researchers are altering dysfunctional immune systems, not just

suppressing them, in a variety of ways that aim to be more potent and

more precise than current therapies.

They’re highly experimental and, because of potential side effects, so

far largely restricted to patients who’ve exhausted today’s treatments.

But people entering early-stage studies are grasping for hope.

“What the heck is wrong with my body?” Mileydy Gonzalez, 35, of New York

remembers crying, frustrated that nothing was helping her daily lupus

pain.

Diagnosed at 24, her disease was worsening, attacking her lungs and

kidneys. Gonzalez had trouble breathing, needed help to stand and walk

and couldn’t pick up her 3-year-old son when last July, her doctor at

NYU Langone Health suggested the hospital’s study using a treatment

adapted from cancer.

Gonzalez had never heard of that CAR-T therapy but decided, “I’m going

to trust you.” Over several months, she slowly regained energy and

strength.

“I can actually run, I can chase my kid,” said Gonzalez, who now is

pain- and pill-free. “I had forgotten what it was to be me.”

‘Living drugs’ reset rogue immune systems

CAR-T was developed to wipe out hard-to-treat blood cancers. But the

cells that go bad in leukemias and lymphomas — immune cells called B

cells — go awry in a different way in many autoimmune diseases.

Some U.S. studies in mice suggested CAR-T therapy might help those

diseases. Then in Germany, Dr. Georg Schett at the University of

Erlangen-Nuremberg tried it with a severely ill young woman who had

failed other lupus treatment. After one infusion, she’s been in

remission — with no other medicine — since March 2021.

Last month, Schett told a meeting of the American College of

Rheumatology how his team gradually treated a few dozen more patients,

with additional diseases such as myositis and scleroderma — and few

relapses so far.

Those early results were “shocking,” Hopkins’ Konig recalled.

They led to an explosion of clinical trials testing CAR-T therapy in the

U.S. and abroad for a growing list of autoimmune diseases.

How it works: Immune soldiers called T cells are filtered out of a

patient’s blood and sent to a lab, where they’re programmed to destroy

their B cell relatives. After some chemotherapy to wipe out additional

immune cells, millions of copies of those “living drugs” are infused

back into the patient.

While autoimmune drugs can target certain B cells, experts say they

can’t get rid of those hidden deep in the body. CAR-T therapy targets

both the problem B cells and healthy ones that might eventually run

amok. Schett theorizes that the deep depletion reboots the immune system

so when new B cells eventually form, they’re healthy.

Other ways to reprogram rogue cells

CAR-T is grueling, time consuming and costly, in part because it is

customized. A CAR-T cancer treatment can cost $500,000. Now some

companies are testing off-the-shelf versions, made in advance using

cells from healthy donors.

Another approach uses “peacekeeper” cells at the center of this year’s

Nobel Prize. Regulatory T cells are a rare subset of T cells that tamp

down inflammation and help hold back other cells that mistakenly attack

healthy tissue. Some biotech companies are engineering cells from

patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases not to attack,

like CAR-T does, but to calm autoimmune reactions.

Scientists also are repurposing another cancer treatment, drugs called T

cell engagers, that don’t require custom engineering. These lab-made

antibodies act like a matchmaker. They redirect the body's existing T

cells to target antibody-producing B cells, said Erlangen's Dr. Ricardo

Grieshaber-Bouyer, who works with Schett and also studies possible

alternatives to CAR-T.

[to top of second column]

|

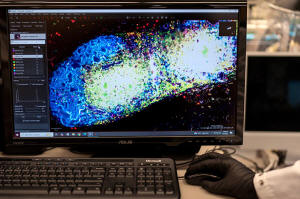

Research fellow Sachin Surwase shows an image of a pancreatic lymph

node from a mouse in the lab where he studies autoimmune diseases at

Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md., Tuesday, May 13, 2025.

(AP Photo/David Goldman)

Last month, Grieshaber-Bouyer

reported giving a course of one such drug, teclistamab, to 10

patients with a variety of diseases including Sjögren’s, myositis

and systemic sclerosis. All but one improved significantly and six

went into drug-free remission.

Next-generation precision options

Rather than wiping out swaths of the immune system, Hopkins’ Konig

aims to get more precise, targeting “only that very small population

of rogue cells that really causes the damage.”

B cells have identifiers, like biological barcodes, showing they can

produce faulty antibodies, Konig said. Researchers in his lab are

trying to engineer T cell engagers that would only mark “bad” B

cells for destruction, leaving healthy ones in place to fight

infection.

Nearby in another Hopkins lab, biomedical engineer Jordan Green is

crafting a way for the immune system to reprogram itself with the

help of instructions delivered by messenger RNA, or mRNA, the

genetic code used in COVID-19 vaccines.

In Green's lab, a computer screen shines with brightly colored dots

that resemble a galaxy. It’s a biological map that shows

insulin-producing cells in the pancreas of a mouse. Red marks rogue

T cells that destroy insulin production. Yellow indicates those

peacemaker regulatory T cells — and they're outnumbered.

Green's team aims to use that mRNA to instruct certain immune

“generals” to curb the bad T cells and send in more peacemakers.

They package the mRNA in biodegradable nanoparticles that can be

injected like a drug. When the right immune cells get the messages,

the hope is they'd “divide, divide, divide and make a whole army of

healthy cells that then help treat the disease," Green said.

The researchers will know it's working if that galaxy-like map shows

less red and more yellow. Studies in people are still a few years

away.

Could you predict autoimmune diseases - and delay or prevent

them?

A drug for Type 1 diabetes “is forging the path,” said Dr. Kevin

Deane at the University of Colorado Anshutz.

Type 1 diabetes develops gradually, and blood tests can spot people

who are brewing it. A course of the drug teplizumab is approved to

delay the first symptoms, modulating rogue T cells and prolonging

insulin production.

Deane studies rheumatoid arthritis and hopes to find a similar way

to block the joint-destroying disease.

About 30% of people with a certain self-reactive antibody in their

blood will eventually develop RA. A new study tracked some of those

people for seven years, mapping immune changes leading to the

disease long before joints become swollen or painful.

Those changes are potential drug targets, Deane said. While

researchers hunt possible compounds to test, he’s leading another

study called StopRA: National to find and learn from more at-risk

people.

On all these fronts, there’s a tremendous amount of research left to

do — and no guarantees. There are questions about CAR-T's safety and

how long its effects last, but it is furthest along in testing.

Allie Rubin, 60, of Boca Raton, Florida, spent three decades

battling lupus, including scary hospitalizations when it attacked

her spinal cord. But she qualified for CAR-T when she also developed

lymphoma — and while a serious side effect delayed her recovery,

next month will mark two years without a sign of either cancer or

lupus.

“I just remember I woke up one day and thought, ‘Oh my god, I don’t

feel sick anymore,’” she said.

That kind of result has researchers optimistic.

"We’ve never been closer to getting to — and we don’t like to say it

— a potential cure,” said Hopkins' Konig. “I think the next 10 years

will dramatically change our field forever.”

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved

|