In 'Mr. Scorsese,' fitting a filmmaking titan into the frame

[October 16, 2025]

By JAKE COYLE

NEW YORK (AP) — The first time the filmmaker Rebecca Miller met Martin

Scorsese was on the set of 2002's “Gangs of New York.” Miller’s husband,

Daniel Day-Lewis, was starring in it. There, Miller found an anxious

Scorsese on the precipice of the film’s enormous fight scene, shot on a

sprawling set.

“He seemed like a young man, hoping that he had chosen the right way to

shoot a massive scene,” Miller recalls. “I was stunned by how youthful

and alive he was.”

That remains much the same throughout Miller’s expansive and stirring

documentary portrait of the endlessly energetic and singularly essential

filmmaker. In “Mr. Scorsese,” which premieres Friday on Apple TV, Miller

captures the life and career of Scorsese, whose films have made one of

the greatest sustained arguments for the power of cinema.

“We talk about 32 films, which is a lot of films. But there are yet more

films,” Miller says, referencing Scorsese’s projects to come. “It’s a

life that overspills its own bounds. You think you’ve got it, and then

it’s more and more and more.”

Scorsese’s life has long had a mythic arc: The asthmatic kid from Little

Italy who grew up watching old movies on television and went on to make

some of the defining New York films. That’s a part of “Mr. Scorsese,”

too, but Miller’s film, culled from 20 hours of interviews with Scorsese

over five years, is a more intimate, reflective and often funny

conversation about the compulsions that drove him and the abiding

questions — of morality, faith and filmmaking — that have guided him.

“Who are we? What are we, I should say?” Scorsese says in the opening

moments of the series. “Are we intrinsically good or evil?”

“This is the struggle,” he adds. “I struggle with it all the time.”

Miller began interviewing Scorsese during the pandemic. He was then

beginning to make “Killers of the Flower Moon.” Their first meetings

were outside. Miller first pitched the idea to Scorsese as a

multifaceted portrait. Then, she imagined a two-hour documentary. Later,

by necessity, it turned into a five-hour series. It still feels too

short.

“I explained I wanted to take a cubist approach, with different shafts

of light on him from all different perspectives — collaborators,

family,” Miller says. “Within a very short amount of time, he sort of

began talking as if we were doing it. I was a bit confused, thinking,

‘Is this a job interview or a planning situation?’”

Scorsese’s own documentaries have often been some of the most insightful

windows into him. In one of his earliest films, “Italianamerican”

(1974), he interviewed his parents. His surveys of cinema, including

1995’s “A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies”

and 1999’s “My Voyage to Italy,” have been especially revealing of the

inspirations that formed him. Scorsese has never penned a memoir, but

these movies come close.

While the bulk of “Mr. Scorsese” are the director’s own film-to-film

recollections, a wealth of other personalities color in the portrait.

That includes collaborators like editor Thelma Schoonmaker, Paul

Schrader, Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio and Day-Lewis. It also

includes Scorsese’s children, his ex-wives and his old Little Italy

pals. One, Salvatore “Sally Gaga” Uricola for the first time is revealed

as the model for De Niro’s troublemaking, mailbox-blowing-up Johnny Boy

in “Mean Streets.”

[to top of second column]

|

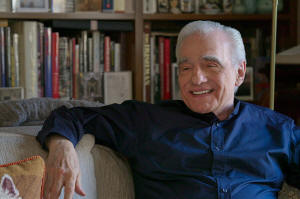

This image released by Apple TV+ shows filmmaker Martin Scorsese in

a scene from the documentary series "Mr. Scorsese." (Apple TV+ via

AP)

“Cinema consumed him at such an

early age and it never left him,” DiCaprio says in the film. “There

will never be anyone like him again,” says Steven Spielberg.

It can be easy to think of Scorsese, perhaps the most revered living

filmmaker, as an inevitability, that of course he gets to make the

films he wants. But “Mr. Scorsese” is a reminder how often that

wasn’t the case and how frequently Scorsese found himself on the

outside of Hollywood, whether due to box-office disappointment, a

clash of style or the perceived danger in controversial subjects

(“Taxi Driver,” “The Last Temptation of Christ”) he was drawn to.

“He was fighting for every single film,” Miller says. “Cutting this

whole thing was like riding a bucking bronco. You’re up and you’re

down, you’re dead, then alive.”

Film executives today, an especially risk-averse lot, could learn

some lessons from “Mr. Scorsese” in what a difference they can make

for a personal filmmaker. As discussed in the film, in the late

’70s, producer Irwin Winkler refused to do “Rocky II” with United

Artists unless they also made “Raging Bull.”

For Miller, whose films include “The Ballad of Jack and Rose” and

“Maggie’s Plan,” being around Scorsese was an education. She found

his films began to infect “Mr. Scorsese.” The cutting of the

documentary took on the style of his film’s editing. “In proximity

to these film,” she says, “you start to breathe the air.”

Nearness to Scorsese also inevitably means movie recommendations.

Lots of them. One that stood out for Miller was “The Insect Woman,”

Japanese filmmaker Shōhei Imamura’s 1963 drama about three

generations of women.

“He’s still doing it,” Miller says. “He’s still sending me movies.”

“Mr. Scorsese” recently debuted at the New York Film Festival, where

Miller's son, Ronan Day-Lewis made his directorial debut with

“Anemone,” a film that marked her husband's return from retirement.

At the “Mr. Scorsese” premiere, a packed audience at Lincoln

Center's Alice Tully Hall came to enthusiastically revel in, and pay

tribute to its subject.

“You hear all those people laughing with him or suddenly bursting

into applause when they see Thelma Schoonmaker or at the end of the

‘Last Waltz’ sequence,” Miller says. “There was a sense of such

palpable enthusiasm and love. My husband said something I thought

was very beautiful: It reminded everyone of how much they love him.”

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved |