|

Jonathan Parker speaks at October

Logan County Genealogical and Historical Society meeting

[October 23, 2025]

At the October Logan County

Genealogical and Historical Society meeting, Jonathan Parker,

Operations Manager at the Lincoln Heritage Museum, provided the

program. The topic of Parker’s presentation was “The Trent Affair of

1861: A Diplomatic Crisis During the American Civil War.”

Parker has served as operations

manager of the museum since August. Before beginning the

presentation, Parker talked briefly about the mission of the Lincoln

Heritage Museum, which is “to interpret the life and legacy of

Abraham Lincoln and the world in which he lived.”

There is an outstanding base of volunteers. Parker said volunteers

at the meeting included Barbara Morrow, Kaylee Parker and Curtis

Fox. They help with the day-to-day operations of running the museum.

The Lincoln Heritage Museum is located at 1115 Nicholson Road on the

campus of the former Lincoln College. They welcome visitors on

Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays from 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM and

Saturdays from 1:00 PM to 4:00 PM. He called them proudly

old-fashioned because “we only take cash or check” but promise the

history is worth it.

Parker said the Lincoln Heritage Museum started as the Lincoln room

in 1941 thanks to a rather large donation of Lincoln artifacts from

Lincoln University alumnus Judge Lawrence Stringer. The collection

grew over time thanks to the generosity of other donors, most

notably Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith, the last descendant of the

Lincoln family.

The Lincoln room grew too small to house the collections and in

2010, the Lincoln College Museum opened up within McKinstry Library.

Parker said the space became too small again and in 2014 the Lincoln

Heritage Museum was formed and given space in the Lincoln Center at

Lincoln college.

Lincoln Heritage Museum consists of two floors. Parker said the

first floor displays over 100 rare objects like furniture owned by

Mr. Lincoln and hand painted campaign banners from the 1860

election. The second floor features the immersion experience, which

takes visitors to Ford’s theatre on the night of Lincoln's

assassination. Visitors then travel with Lincoln as he lay dying at

the Peterson house. The rooms recreate Mr. Lincoln's life and times

and show the character of the man and president we know from our

history books was forged.

Parker said the Lincoln Heritage

Museum strives to be an educational resource to the community and

all are invited to learn from Lincoln and to live like Lincoln. He

invited everyone there to come visit soon.

Parker discussed the details of the

Trent Affair of 1861, which was a diplomatic crisis Lincoln had to

face at the start of the Civil War. Parker then took everyone back

to one of the most dangerous moments of the Lincoln presidency. It

was a moment when the United States, already torn apart by its Civil

War, nearly found itself at war with Great Britain as well.

In 1861, Parker said the Civil War had just begun and the union was

fighting to preserve itself. The confederacy was desperate for

recognition as an independent nation, but Parker said the union was

anxious to stop the confederacy from being recognized at almost any

cost.

Charles Francis Adams, son of former president John Quincy Adams was

serving as the U.S. Minister to the United Kingdom at the start of

the Civil War in 1861. On November 12th, 1861, Adams received a

request for a private meeting with the British Prime Minister, Lord

Palmerston.

Parker said the invitation read, “my dear Sir I should be very glad

to have a few minutes conversation with you. Could you without

inconvenience call upon me here today at any time between 1:00 and

2:00?”

Foreign representatives typically met with the British Foreign

Secretary, so Parker said a summons from the Prime Minister himself

was very much out of the ordinary.

Lord Palmerston got straight to business when Adam showed up for his

appointment. Palmerston told Adams that the captain of the American

warship James Edgar had gotten gloriously drunk and bragged about

his plans to intercept a British ship bringing Confederate diplomats

to Europe. The British knew that the confederacy wanted their

government and the French government to officially recognize them as

an independent nation.

Parker said Palmerston let Adams know that any interception by

America of Confederate diplomats would probably not lead to any

good. Palmerston and Adams did not know that four days before on

November 8th, Captain Wilkes and the USS San Jacinto captured James

Mason and John Slidell, the Confederate diplomats, from the British

mail steamer Trent off the coast of Cuba.

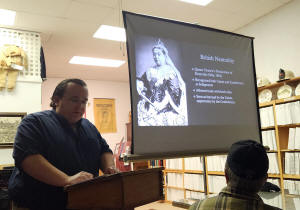

Queen Victoria issued the United

kingdom's declaration of neutrality in the American Civil War in May

1861 in response to President Lincoln's decision to blockade the

South's ports. Parker said the declaration named both sides as

belligerent. It allowed the British to trade with both the Union and

Confederacy. He said this recognition was the only important

concession that the United Kingdom made to the Confederacy during

the Civil War since the British never recognized the independence of

the Confederacy.

Parker said the United States saw Queen Victoria's declaration as a

betrayal of the United Kingdom's alliance with America and its

international opposition to slavery. The Confederacy was thrilled

with the Queen's declaration as they saw it as an opening to get

European powers to recognize them as an independent nation.

Recognition as a country would

allow the Confederacy to borrow from international lenders to fund

their war effort. Parker said a priority of the Confederate

government after this declaration was to send envoys to Britain and

France to lobby for full recognition of nationhood. Confederate

states were counting on the power of “king cotton” to bring Britain

to their aid.

Prior to the war, Parkes said Britain and the rest of Europe

imported a full 85 percent of its cotton from the Confederacy.

Nearly 20 percent of the British population earned its living from

the cotton industry and 10 percent of the country's capital was tied

up in cotton as well. Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government

felt that the war would be a short one and if it went on longer the

cotton famine would bring Great Britain into conflict to protect

economic interests and rescue the south from Union forces.

Parker said the Confederate diplomats, Mason and Slidell,

successfully ran the Union blockade aboard the USS Nashville as far

as Charleston and went from Charleston to Nassau in the Bahamas

aboard the ship Theodora. The men missed their connection with the

British ship to take them to Europe and sailed to Cuba hoping to

find a ship bound for England.

After three weeks, Parker said the men were finally able to book

passage on the RMS Trent when she was ready to sail out of Havana.

Captain Charles Wilkes of San Jacinto learned from a newspaper that

Mason and Slidell were in Havana and waiting to sail on the RMS

Trent, so Wilkes consulted with his first officer Lieutenant Fairfax

about the legality of removing Confederate envoys from a British

steamer. Wilkes and Fairfax decided the diplomats could be

considered contraband and legally seized.

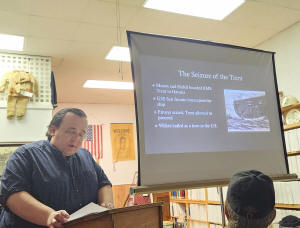

The Trent left harbor in Havana on November 7th and was found by the

San Jacinto. Parker said Wilkes ordered two shots fired across the

bow of the Trent. The first shot was ignored but after the second

shot, the Trent stopped. Twenty heavily armed men were allowed to

board the vessel with the following instructions: should Mr. Mason,

Mr. Slidell or their secretaries Mr. Eustace and Mr. McFarland be on

board, make them prisoners and send them on board this ship

immediately and take possession of the Trent as a prize.

Parker said Fairfax was also

instructed to seize any dispatches and official correspondence he

might find. Fairfax did not wish to make the situation any worse

than it already was, so he chose to board the Trent alone. At first

Fairfax found the captain of that vessel to be uncooperative.

Fairfax was being threatened by the passengers and crew and had

little choice but to order his armed sailors to join him on board.

James Marr refused permission for the boarding party to search the

ship, but Parker said at this point Mason and Slidell came forward

willingly to avoid any bloodshed. Fairfax backed down as he realized

that searching the ship would have constituted a defacto measure of

the British vessel. Mason and Slidell formally refused to go with

Fairfax but offered no resistance when being escorted off the Trent.

There were no dispatches or any

papers of import on the two as the dispatches had previously been

given to the agent who had promised to deliver them to the

Confederate authorities in London. The Trent was then allowed to

proceed on to London.

Mason and Slidell went down to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. In the

United States, Parker said Wilkes was hailed as a hero for his

actions and received a gold medal.

Others in the north worried the capture of Mason and Slidell would

lead to war. Parker said there were many comparisons made between

Captain Wilke’s actions and those of the British up to the War of

1812.

On November 27, when news broke in

London of the seizure of Mason and Slidell, Parker said the British

public and government were predictably furious. The British were

livid that the United States had disrespected their sovereignty.

At a cabinet meeting, Prime Minister Palmerston shouted, “I don't

know whether you were going to stand this, but I'll be damned if I

do.” Parker said Palmerston calmed down a bit after that meeting and

left the door open for a diplomatic solution.

[to top of second column] |

Palmerston wrote to Queen

Victoria a few days after and said if the Americans would

apologize, the result would be honorable for England and

humiliating for the United States.

In the meantime, Parker said all the United States Minister

Charles Francis Adams could do in the meantime was send letters

to Secretary of State Seward to let him know the mood in London.

Adams could not speak on behalf of the American government

without explicit instructions from

Seward. The only course of action available to minister Adams

was to wait and avoid Lord Russell.

Within a week of the Trent crisis taking place, Parker said

Secretary of War Sir George Lewis proposed sending 30,000 men to

Canada. Lord Palmerston instructed the Governor General of

Canada prepare for war saying such an insult to our flag can

only be atoned by the restoration of the men who were seized.

Everyone agreed something ought to be done in response to

America's

violation and British flag, but they couldn't agree on what

response to take William Gladstone Chancellor of the Exchequer

felt it was too strong of a response would leave the Americans

with no room to maneuver. Lord Palmerston considered it too weak

of a response and felt it gave the United States the wrong

impression of British resolve.

Parker said the cabinet decided to leave the drafting of the

government’s response to Foreign Secretary Lord Russell.

Russell's reply stated the facts of the case and demanded the

Americans restore the Confederate commissioners to the British

and issue a formal apology within a week of receipt of the

letter.

If the Americans refused to comply, Parker said Lord Lyons, the

British Ambassador to America would close the embassy and leave

for Canada and a de facto state of war would exist between

Britain and the United States. When the British cabinet

reconvened the next day to look at the draft letter, some felt

the meaning of the text was unclear and Russell became

defensive. Parker said the cabinet agreed to send Lord Lyons two

letters: one that outlined the basics of the case and the second

that contained the threat of war.

Within a week, Parker said more disagreement ensued and the

cabinet agreed to send two letters to the queen. The letters

arrived at Windsor Castle on November 30th. Prince Albert, Queen

Victoria’s husband, had been kept up to date with the cabinet’s

deliberations and was convinced that their reaction would be

overly aggressive. Parker said he was absolutely correct.

Prince Albert had a serious case of typhoid fever and was barely

able to hold a pen, but Parker said the prince amended the

proposed text. Prince Albert felt there should be the expression

of hope the American captain did not act on their instructions,

or if he did he misunderstood them. Prince Albert wrote that the

United States government must be fully aware that the British

government could not allow the flag to be insulted and the

security of her mail communications to be placed in jeopardy. He

wrote Her Majesty's government aren't willing to believe that

the United States government intended wantingly to put an insult

upon this country so the whole thing was a mistake, and it was a

rogue captain acting without any sort of instruction at all.

Parker said Prince Albert was hoping to get a suitable apology.

It was a loophole, and Parker called it an exit route that would

allow the American government to withdraw with honor. This was

the last document Prince Albert would ever sign as he collapsed

the next day and died twelve days later at the age of 42.

Lord Russell agreed with the prince’s changes, but Parker said

he still doubted that Seward would climb down. A third letter

written to Lyons outlined the presentation of Her Majesty's

demands and said above all the Confederate commissioners must be

released from prison. Parker said no apology would appease

Britain if they were kept in custody. There was to be no

bargaining on that point.

Parker said Steward got Lincoln to call a cabinet meeting for

Christmas Day and copies of Russell's letter were given to the

members. It soon became apparent most were against releasing the

Confederate envoys. Public opinion adored Captain Wilkes and to

release Mason and Slidell seemed like surrender. However, the

economic reality was grim because U.S. bonds were collapsing and

a war with Britian would be ruinous.

The cabinet adjourned in the afternoon agreeing to reconvene the

next day with Lincoln still clinging to the notion of

international arbitration of the crisis. Parker said Lincoln

asked Seward to present his arguments on compliance and writing

the next day and Lincoln would do the same for the arbitration

case.

By the next day, most cabinet members had come to Seward’s view

and the United States had little choice but to comply with

British demands which was very sensible. Seward had been up all

night drafting a 26 page response to Lord Russell in which he

clearly laid the blame on Captain Wilkes and his failure to take

the Trent.

Seward outlined his case then waited for Lincoln to make his for

arbitration, but the president said nothing and the cabinet

approved Seward’s proposal. When Lincoln was asked why he had

not made a counter argument, Parker said Lincoln replied, “I

could not make an argument that would satisfy my own mind.”

Parker said Steward’s official

reply complied with the basic demands of the Russell letter stating

Wilkes acted without orders. The captives would be released, but

there would be no formal apology. The envoys were contraband and

could be rightfully seized. Wilkes's error was in not seizing Trent

as well and taking it to a neutral port for judgment.

In a final poke at the British, Seward suggested that Wilkes by

impressing passengers from a merchant ship had merely followed

British practice not American, which Parker said was an echo of the

War of 1812. However, Steward said the United States wanted no

advantage gained by an unlawful action and as far as the nation was

concerned the captives were relatively unimportant.

Steward then concluded the four persons in question are now held in

military custody in Fort Warren, Massachusetts and they will be

cheerfully liberated. He asked Lord Lyons to please indicate a time

and place for receiving them. Lord Lyons accepted the diplomatic

overture of the United States. Parker said on January 3, 1862, Mason

and Slidell left for England.

In England, the American response was awaited eagerly and with some

trepidation. On January 8, 1862, the news reached London and spread

rapidly across the city. Parker said the press conveyed a sense of

relief with the Times commenting, “we draw a long breath and are

thankful we have come out of this trial with our honor saved and no

blood spilled.”

Parker said the Times judged Mason and Slidell “about the most

worthless booty possible to extract from the jaws of the American

Lion.”

Palmerston wrote to the queen reporting the humiliation of the

United States. Parker said Queen Victoria’s speech at the opening of

Parliament February 6, 1862, officially closed the Trent Affair and

she told them the question has been satisfactorily resolved. He said

the friendly relation between the Queen and the President of the

United States remained unimpaired.

When Mason and Slidell arrived at

Southampton that February, Parker said Queen Victoria refused to

receive them. Their arrival after a long journey was barely reported

in the British press.

The soldiers Britian had sent to Canada at great expense remained

there for some time. Parker said they got bored with little to do.

Some even went to America and joined the union army.

The South gained little from the

Trent Affair. Parker said in late February, the British government

issued a report acknowledging the effectiveness of the Union

blockade.

After a debate in the House of Lords on March 10, Mason sent one of

his first dispatches to Richmond reporting the blockade was

effective and no step would be taken by this government to interfere

with it.

With the Queen’s honor defended and a cheaper alternative to

southern cotton located in India, Parker said Great Britian could

afford to stay on the sidelines while the Americans killed each

other.

In the end, Parker said the inherent good sense of Prince Albert,

Lord Lyons and William H. Seward had avoided the looming threat of

war between the United States and Great Britian. It also allowed

Abraham Lincoln to fight one war at a time.

Next, Parker asked if anyone questions.

Curt Fox asked about the importance of the Confederate diplomats and

if there was any diplomatic immunity.

Parker said the men were “a

middling sort of Southern aristocrat.” If the Confederacy had been

recognized as an independent nation, he said there would have been a

sort of diplomatic immunity. Since no one recognized the Confederacy

as a nation, there was no such protection.

Diane Farmer asked how Queen Victoria felt about slavery. Parker

said the queen abhorred slavery and racism.

Monday, November 17, the Logan County Genealogical and Historical

Society will have its annual dinner meeting. It will be held at the

Lincoln American Legion’s Mary Pat room. Doors open at 6 p.m. with

dinner at 6:30 p.m. Reservation forms can be picked up at the LCGHS

building on 114 N. Chicago on Tuesdays, Thursdays or Fridays between

11 a.m. and 3 p.m. Forms and a payment of $25 for the dinner can be

mailed or dropped off and need to be in by Wednesday, November 5.

The program that evening will be presented by Bill Furry of the

Illinois State Historical Society.

[Angela Reiners]

|