Kentucky distillery bounces back from massive flood that briefly halted

bourbon production

[September 24, 2025]

By BRUCE SCHREINER

FRANKFORT, Ky. (AP) — The long history of bourbon production at Buffalo

Trace Distillery has been connected to the Kentucky River — summed up as

a blessing and curse by a plaque on the grounds.

In the 1800s, long before the Buffalo Trace name was attached to the

distillery, the river served as a floating highway to bring in grain and

other production essentials and to transport barrels of whiskey to

markets along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Even today, river water

cools down production equipment. But the river flowing past the

distillery flashed its destructive side in April.

A massive flood, caused by days of unrelenting rain, sent the Kentucky

River surging over its banks, inundating most of the 200-plus-acre

distillery grounds on its main campus in Frankfort. Nearly every phase

of production was impacted, as were several warehouses where whiskey is

aged.

“It was just something that was hard to process, but we knew we couldn’t

take too much time to process it,” said Tyler Adams, a distillery

general manager. He said they had much to do to recover from the

reservoir of murky water that swamped the bourbon-making campus.

Whiskey production bounces back

Five months later, production at the distillery is back to normal,

including of some of the most sought-after bourbons. Its lineup includes

the namesake flagship brand, Buffalo Trace, as well as Eagle Rare, W.L.

Weller and Blanton's. Pappy Van Winkle bourbons are distilled and aged

at Buffalo Trace while the Van Winkle family remains in control of the

coveted brand.

The distillery recently filled its 9 millionth barrel of bourbon since

Prohibition, just two and a half years since filling the 8 millionth

barrel. It has also introduced new whiskeys to its catalogue and is

renovating a campus building into a cafe and events center.

The cleanup enlisted hundreds of plant employees and contract workers.

Buffalo Trace fans swamped the distillery with offers to pitch in, Adams

said. The distillery politely declined and suggested they might assist

area residents instead.

Crews removed debris, sanitized equipment and pumped out what was left

after floodwaters receded. Bourbon barrels swept into the parking lot

caught some attention, Adams said. No chance for sneak samples, though —

the barrels were empty.

Few visible reminders remain of that mud-caked, debris-strewn mess.

Some filled whiskey barrels touched by floodwaters were still being

cleaned and tested, but the meticulous task of examining thousands of

barrels was nearly complete, the distillery said. Quality control

assessments found only small amounts of aging whiskey were impacted.

High water marks are etched into some buildings and tour guides casually

remind visitors of the epic event.

Danny Kahn, a master distiller for Buffalo Trace's parent company, says

he still experiences “a little PTSD” when recalling those frantic days.

River flooding has been a sporadic part of the distillery's history —

including big ones in 1937 and 1978, but in early April, the floodwaters

surged to previously unseen heights. Buffalo Trace had also just

completed a decade-long, $1.2 billion expansion to double distilling

capacity.

“It actually looked kind of calm, but I knew that it was not calm

because we could see buildings were under 10 feet (3 meters) of water,”

Kahn said. “It was really quite overwhelming.”

Activating their flood plans, workers shut down the distillery and did

what they could to safeguard equipment. After that, all they could do

was watch and wait. Distillery officials observed the devastation from

higher ground and via drone footage.

[to top of second column] |

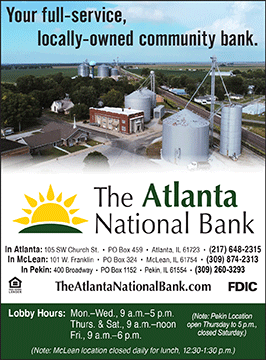

In an aerial view, the Buffalo Trace Distillery is seen on Sept. 16,

2025, in Frankfort, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

Once the river crested, it took a few days for the floodwaters to

fully recede, but operations gradually sprung back to life. Finished

whiskey shipped out the day after the rain stopped. Bottling soon

resumed and a makeshift gift shop opened until the visitors' center

was repaired. Tours eventually resumed. But bourbon production

halted for about a month as the cost for cleanup and repairs

surpassed $30 million.

Several storage tanks shifted off their foundation. Some were

repaired, others replaced. Dozens of electrical control panels were

destroyed. About three-fourths of gift shop inventory was lost.

“It was just defeating to watch all this flooding and to realize

that we’re going to be down for a while,” Kahn said. “Just the

apprehension of how much work this is going to be to fix. And when

we finally got it done, it was really a sigh of relief and we get

back to business as normal.”

Hard times in the whiskey sector

For the American whiskey industry as a whole, it's been anything but

business as usual.

After years of growth, prospects turned sour for the sector amid

sluggish sales and trade uncertainties as President Donald Trump

imposed sweeping tariffs.

In 2024, American whiskey sales in the U.S. fell nearly 2%, the

first such drop in supplier sales in more than 20 years, the

Distilled Spirits Council said. Initial data for the first half of

2025 showed a continued decline, it said. American whiskey exports

dropped more than 13% through July of this year compared to the

year-ago period, it said. The American whiskey category includes

bourbon, Tennessee whiskey and rye whiskey.

Lower domestic sales stem from a mix of market challenges, including

supply chain disruptions and changes in consumer purchasing trends,

said Chris Swonger, the council's CEO.

“While there’s ongoing debate about whether these are temporary

headwinds or signs of a more fundamental shift in consumer behavior,

large and small distilleries across the country are under pressure,”

Swonger said in a statement.

Kentucky distilleries producing such prominent brands as Buffalo

Trace, Jim Beam, Maker’s Mark, Woodford Reserve, Wild Turkey and

Four Roses can weather downturns better than small producers.

Heaven Hill Brands, another large producer, recently celebrated its

new $200 million distillery in Bardstown, Kentucky, taking a long

view of market prospects by significantly boosting bourbon capacity.

“As an independent, family-owned company, we don’t have to chase

quarterly trends; we’re building for the next generation,” said Kate

Latts, co-president of Heaven Hill Brands, whose brands include Evan

Williams and Elijah Craig. “This distillery reflects that

philosophy.”

At Buffalo Trace, its future is entrenched alongside the Kentucky

River, realizing that more floods could come in the years ahead. The

distillery learned lessons to be even better prepared next time.

“This area being a National Historic Landmark, being right on the

river, there’s only so much you can do to hold back that water,”

Adams said. “Your best bet is to prepare for it, do what you can.

But holding back that water? It’s really inevitable it’s going to

make it into some spaces.”

All contents © copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved |