|

Features,

Animals

for Adoption,

Out

and About Travel

News Elsewhere (fresh daily

from the Web) Home and

Garden News Elsewhere (fresh

daily from the Web)

|

|

Features

|

|

|

|

|

Animals

for Adoption

|

|

These animals and

more are available to good homes from the Logan County Animal

Control at 1515 N. Kickapoo, phone 735-3232.

Fees for animal

adoption: dogs, $60/male, $65/female; cats, $35/male, $44/female.

The fees include neutering and spaying.

Logan County Animal

Control's hours of operation:

Sunday – closed

Monday –

8 a.m. - 5 p.m.

Tuesday –

8 a.m. - 5 p.m.

Wednesday –

8 a.m. - 5 p.m.

Thursday –

8 a.m. - 5 p.m.

Friday –

8 a.m. - 3 p.m.

Saturday –

closed

Warden: Sheila Farmer

Assistant: Michelle Mote

In-house veterinarian: Dr. Lester Thompson

|

DOGS

Big to

little, most these dogs will make wonderful lifelong companions when

you take them home and provide solid, steady training, grooming and

general care. Get educated about what you choose. If you give them

the time and care they need, you will be rewarded with much more

than you gave them. They are entertaining, fun, comforting, and will

lift you up for days on end.

Be prepared to take the necessary time when you bring home a

puppy, kitten, dog, cat or any other pet, and you will be blessed.

[Logan

County Animal Control is thankful for pet supplies donated by

individuals and Wal-Mart.]

|

|

|

|

Ten reasons to adopt a

shelter dog

1.

I'll bring out your

playful side!

2.

I'll lend an ear to

your troubles.

3.

I'll keep you

fit and trim.

4.

We'll look out for each other.

5.

We'll sniff

out fun together!

6.

I'll keep you

right on schedule.

7.

I'll love you

with all my heart.

8.

We'll have a

tail-waggin' good time!

9.

We'll snuggle

on a quiet evening.

10.

We'll be

best friends always.

|

|

|

CATS

[Logan

County Animal Control is thankful for pet supplies donated by

individuals and Wal-Mart.]

|

|

Warden

Sheila Farmer and her assistant, Michelle Mote, look forward

to assisting you. |

| In

the cat section there are a number of wonderful cats to

choose from. There are a variety of colors and sizes.

Farm

cats available for free!

|

|

|

[Mixed kittens. One male, one female.

Will be good family pets or farm cats.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Part

3

Funk

family members

had a wide range of talents

[SEPT.

24, 2001]

The

artifacts in the Funk Prairie Home and Gem and Mineral Museum

demonstrate that, while this colorful and prominent central Illinois

family were ahead of their time in farming practices, family members

also developed many other talents. DeLoss Funk, younger son of

LaFayette, for example, became an early expert in the new science of

electricity and wired his farm home for electricity 15 years before

the homes in nearby Bloomington had electric power.

|

|

[Click

here for Part 1]

[Click here

for Part 2]

Of

course, there were no power plants for DeLoss to hook into at that

time, so he built his own generator. The cement building close to

the house houses a gasoline engine that he built to power the 110

volt generator.

In the

kitchen, where the furniture is vintage 1910-1920s, DeLoss provided

outlets to the kitchen island

— a big wooden table

— that could

power a fan, a waffle iron, a toaster, a chafing dish and a vacuum

cleaner. In a time when irons, often called sad irons

because the amount of hard labor they required, were heated on a

wood or coal stove and rushed to an ironing table, the Funk family

had a choice of two types of electric irons: a shirtwaist iron and a

smoothing iron.

DeLoss

also provided his mother with an electric washing machine, attached

with a belt drive to a butter churn, so she could wash clothes and

churn butter at the same time. This was four years before the first

commercial electric washing machine was available, tour guide Bill Case explains.

The

Funks also had grass tennis courts, and DeLoss provided lights for

them so people could see to play at night. He also built a fountain

with colored lights in the formal flower garden south of the house,

which was used on special occasions.

The

upper floor of the house had five bedrooms and a nursery, as well as

another bathroom. In the guest bedroom was a tin ceiling and the

rest of the "fancy" furniture that came from Philadelphia:

a bed, a large dresser and a washstand. The large dresser has a

long, flat, hidden drawer in the bottom where the family could hide

their land deeds, the most valuable possessions they owned.

The

washstand was kept in the guest room even though the room contained

a sink with hot and cold running water. But because many folks at

that time were not familiar with running water and might have been

afraid to try using the sink, the Funks, always concerned for the

comfort of their guests, provided the washstand with a bowl and a

pitcher of water as well.

A bed

in one of the family bedrooms still has a corn shuck mattress. Former

caretaker Bertha Hedrick, who lived in the house, slept on the corn

shuck mattress for 15 years and said it was the best sleep of

her life. She described it as "like a crunchy waterbed but a

bit noisy."

The

Funks were democratic from the beginning, as the servant’s room

will attest. It is large and pleasant, with windows on two sides, a

comfortable bed, a desk, a wardrobe and chairs. It also has its own

stairway to the back porch, so the cook or caretaker who lived there

could come and go, or have visitors without disturbing the family or

being disturbed.

The

most unusual feature, however, is the painted floor. The other

floors upstairs are pine but are not painted. Paint was very

expensive in those days, Case explains, and the painted floor was a

sign of the high regard the family had for their help.

The

Funks paid their help well, Case says, and treated them much like

family members. In fact, some of the help married into the Funk

family.

When

LaFayette and Elizabeth died, DeLoss and his wife and three

daughters moved into the home. His family were the last Funks to

live in the Prairie Home. LaFayette’s other son, Eugene, usually

called E. D., and his family, four sons and four daughters, lived a

few miles down the road. E. D. raised, cattle, hogs and sheep, but

early on he turned his attention to improving corn. In 1901 he

formed the Funk Brothers Seed Company and began working to improve

the yield of corn and soybeans.

[to top of second column in

this section]

|

E.D.

began experimenting with closely bred families of corn and in 1916

marketed the first commercial "hybrid" corn, although that

corn was not the hybrid corn farmers know today. However, E.D. and

his staff kept working to develop corn that could withstand disease,

drought and the storms that leveled rows of corn in the fields, and

by the 1920s the Funk Farms near Bloomington had become a gathering

point for scientists interested in hybrid corn. By the mid-1920s

true hybrids were being developed, and by the mid-1930s new and more

effective strains of hybrid corn were coming from the Funk Farms

Experiment Station.

For

seven decades the company remained under the ownership and

management of the Funk family. E.D.’s son, Eugene D. Funk Jr.,

often known as Gene, continued the seed corn business and was

himself a prominent civic leader.

Another

of E.D.’s sons, LaFayette II, developed a lifelong fascination

with minerals and gems. LaFayette traveled worldwide as a

construction engineer for the Funk Seed Company, and on whatever

continent he was in, whether in Europe, South America, Asia or

Africa, he collected specimens.

His

collection became so extensive that he decided to build his own

museum on the grounds of the Funk Family Home in 1973. He also

donated collections of minerals to Illinois State University,

Wesleyan University and the University of Illinois. Still, the

building a few steps from the Prairie Home, which displays rocks on

the outside as well as the inside, houses room after room of

beautiful and unusual specimens that bring "rock hounds"

and mineralogists from all over the world to visit.

One of

the largest one-man collections in the world, most of the gems and

minerals are shown in their natural, uncut condition, but some are

cut and polished. There are also separate collections of fossils,

central Illinois Native American artifacts, Chinese soapstone

carvings, sea shells and corals, and a room of fluorescent minerals

which glow under ultraviolet light.

Next

to the Gem and Mineral Museum, a collection of posters and pictures

tells the story of the Funk Brothers Seed Company, and the visitor

will see signs advertising the well-known Funk’s G hybrid seed corn.

This part of the museum is still not complete, and new pieces are

added regularly.

A

collection of carriages that belonged to members of the Funk family,

along with one that belonged to their doctor, are also on display.

Another

Funk, Paul Allen, a brother of LaFayette II and Gene, is the

founder of the trust fund which maintains the Prairie Home and the

other museums. Still another descendent of the Funk family, Rey

Jannusch, a great-granddaughter of LaFayette I, is manager of the

home and curator of the museums.

Today,

on the south lawn are a formal flower garden and an herb garden. The

latter is planted and tended by the Herb Guild of McLean County and

is divided into sections: herbs for cooking, herbs for medicinal

use, herbs for dyeing and herbs used in biblical times.

In the

center of the herb garden is a knot garden, an arrangement of

low-growing flowers that should look from above as if they are tied

in a bow. Last year, Case said, the knot garden suffered damage in

the harsh cold weather.

Although the Funk Brothers

Seed Company is no longer an independent Bloomington-area business

and although Funks no longer live in the Prairie Home, the legacy of

this remarkable family still lives on in Illinois.

(For a tour of the Funk

Prairie Home and Gem and Mineral Museum, call (309) 827-6792. Tours

are available Tuesday through Saturday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., March

through December. Tours range from individuals to groups of 50 and

are free of charge.)

[Joan

Crabb]

|

|

|

Part

2

Funk home

was both

comfortable and impressive

[SEPT.

10, 2001]

When

LaFayette Funk brought his bride Elizabeth home to Illinois, he

presented her with his wedding gift — the spacious, graceful

13-room country home near Shirley, south of Bloomington, that is

today the Funk Prairie Home. He built it himself with lumber from

the family land at Funks Grove, just down the road.

|

|

[Click

here for Part 1]

When

he and Elizabeth moved in, in January of 1865, the house was not

completely finished inside. It took them 10 years to complete the

home and furnish it the way they wanted.

Although

first and foremost the Prairie Home was a home, LaFayette, like his

father, was a public person, and he often entertained visitors,

perhaps the governor or another state official, perhaps farmers from

the United States and other countries who came to see the model farm

on the Illinois prairie. The Funks were so far ahead of their time

in farming practices, people came from far away to learn from them,

according to Bill Case, guide and caretaker of the home.

LaFayette

followed in his father’s footsteps as a "cattle king"

and was a founder and director of the Chicago Union Stockyards. Like

his father, too, he was both a state representative and a state

senator. He was prominent in Illinois agriculture, serving for

nearly 25 years on the State Agricultural Board. This board worked

for laws which would benefit farmers, helped plan courses of study

at the University of Illinois agricultural college, and took part in

planning and staging the 1983 World’s Fair in Chicago.

So

LaFayette and Elizabeth’s home was both comfortable and

impressive. Guests entering the front hall saw a stamped tin ceiling

and a fine large hall tree, complete with mirror. The hall tree is

one of six pieces made by a carpenter "out east," where

the best furniture was made at that time.

LaFayette

and Elizabeth had gone to the United States Centennial in

Philadelphia in 1876, where they saw furniture that was made as a

gift for President Ulysses S. Grant. They had been saving money for

10 years to buy the kind of wood pieces they wanted, so they found

the firm that made Grant’s furniture and ordered six pieces for

their home on the prairie. Grant’s furniture is now in Blair House

in Washington, D.C., while LaFayette and Elizabeth’s furniture is

still in the Prairie Home, along with most of the other pieces they

purchased.

All

six pieces have a rosewood base, with burled walnut and, on most

pieces, bird’s eye maple veneer. Superb handiwork and detailed

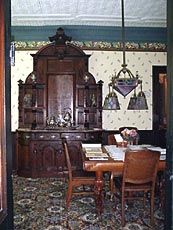

wood carving make them still impressive 125 years later. Downstairs,

along with the hall tree, is a massive desk-bookcase, sometimes

called a "secretary," which sits in the library next to

the living room. A 10½-foot sideboard dominates the dining room.

The other three pieces are in the guest bedroom upstairs.

In the

parlor, just off the front hall, hang portraits of Isaac and

Cassandra, LaFayette’s parents. Here, too, is a Chickering square

grand piano, made by the famous Boston firm and bought by the Funks

in Chicago. Although most furniture was shipped by railroad at that

time, this piano was brought to the Funk home by oxcart, making the

trip from Chicago in just three days.

The

parlor, always the most elegant and least used room in a house of

that time, has a fine Italian marble fireplace (even though the home

had hot-water central heating), also a floor-to-ceiling pier glass

between two windows. The pier glass, Case explains, was called that

not because people "peer" into it, but because it came by

ship from Europe and had to be picked up at the dock or

"pier" when it was unloaded.

The

living room, separated from the parlor by a golden oak archway, was

the place for family and close friends to gather. Although this

room, too, has an Italian marble fireplace, the furniture is not so

impressive, just what people of that time could buy through the

Sears, Roebuck catalog.

The

highlight of the living room tour is the 1913 Victrola. Case winds

it up and puts on a record to play for visitors, perhaps the song

"To Any Girl," recorded in 1904 by Alexander Campbell and

Henry Burr.

[to top of second column in

this section]

|

Although recording techniques at that time did not pick

up bass sounds nearly as well as they do today, the music still

sounds amazingly good. Perhaps that is because of the bamboo needles

that play the thick, old 78 rpm records. The Funks always thought

ahead, so along with a huge supply of these bamboo needles, the

Funks also had a needle sharpener. Those needles will last another

hundred years, Case says.

Elizabeth,

a talented musician, must also have loved the Swiss music box that

sits on a small table in the living room. Case winds it up so

visitors can hear one of the five tunes it can play.

Off

the living room is the library, with the big secretary. Accessible

from both the library and the dining room was a real luxury for an

early farm family — an indoor bathroom with a zinc-lined tub and a

toilet. Water was pumped into a tank in the attic to operate the

gravity-flush toilet.

The

dining room could seat 16 comfortably for dinner. The big sideboard

and the bay window are focal points in the room.

Not

only most of the furniture but even some of the houseplants are

original. On the plant stand in the bay window is Elizabeth’s

Christmas cactus, now 125 years old, which she brought back from the

United States Centennial celebration in Philadelphia in 1876. A

cutting from a night-blooming cereus, also 125 years old, is on the

plant stand as well.

On the

table is Volume I of the Funk-Stubblefield family tree. This book

has 800 pages, and Volume II is in the works.

Above

the table hangs an electric light fixture that looks as if it might

have been designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, or at least someone

well-known in the Arts and Craft movement. This, and the kitchen,

demonstrate that members of the Funk family possessed a wide array

of talents.

LaFayette

and Elizabeth had only three sons, one of whom lived just a few

years. The oldest, Eugene Duncan Funk, usually known as E.D., became

a noted seedsman who pioneered the use of hybrid corn. The youngest,

Marquis DeLoss, branched off in a new direction. Sent to the

University of Illinois to study farming, DeLoss instead signed up

for courses in the new science of electricity. At the U of I he

built an internal combustion engine and became the university

president’s chauffeur.

When he came home again,

he put his talents to use in the Prairie Home. Not only did he

design and build the light fixture in the dining room, he provided

his home with electrical appliances that most people didn’t dream

existed, let alone hope to own. In 1910, the farm had so many

electric lights journalists called it "The City on the

Prairie." DeLoss was "light years ahead of his time,"

Case explains, because the city of Bloomington didn’t have

electric lights for another five years, and ordinary rural people

didn’t have electricity for another 15 years.

(To be continued)

[Joan

Crabb]

[Click

here for Part 3]

|

|

|

Part

1

Funk

Prairie Home tells story of prominent, colorful central Illinois

family

[SEPT.

8, 2001]

Not

every tourist attraction makes you want to pull up a chair and just

sit awhile on its front porch, or perhaps wander through its lawn

and gardens. But the Funk Prairie Home, a little gem of a museum

near Shirley, south of Bloomington, does just that.

|

|

This

inviting country home also gives visitors a pleasant and painless

history lesson, a look at a prominent rural family whose

accomplishments are interwoven with the story of our state and

nation.

And if

that isn’t enough, part of this gem of a museum includes a museum

of gems, room after room of cut and uncut gems and minerals from all

over the world. Another section of the museum, still a work in

progress, tells the story of the Funk Brothers Seed Company, which

became a major producer of hybrid corn in the United States and

abroad.

Perhaps

the most important feature of the Funk Prairie Home is that it still

keeps the feeling of the comfortable, welcoming place it was in the

days when the man who built it, Lafayette Funk, entertained

important political and business leaders there. This impression is

helped along by the tour given by guide and caretaker Bill Case, who

somehow makes you feel you are one of those honored guests who were

entertained by LaFayette and his wife Elizabeth.

"The

Funks knew what hospitality was and how to make you feel at

home," Case says. "Our mission, different from that in the

grand showplace homes like the David Davis mansion in Bloomington,

is to educate people about the Funk family and life back when they

were living here.

"We

want people to feel like they’ve been in a home, not in a museum.

We want them to feel they’ve been a part of what they are seeing.

The tour is about the people who lived here, not just about the

stuff you see here. History isn’t just stuff."

The

"stuff" in the 13-room house, however, reflects the

interesting lives of the Funk family, as does the house itself.

Built in 1863-64, it was a wedding present for Elizabeth Paullin of

Ohio, whom LaFayette met and fell in love with while in college.

Although

LaFayette insisted upon bringing his bride to a comfortable and

spacious home, he himself was born and spent his early years in a

log cabin. His father, Isaac Funk, a man of German descent who come

to Illinois from Ohio, and his mother, Cassandra Sharp of the Fort

Clark area (now Peoria), homesteaded on the McLean County prairie in

a one-room cabin located at what is now the Funk’s Grove rest stop

along Interstate 55.

Isaac

and Cassandra had 10 children, nine of whom lived to the age of 50

or more, unusual at that time. LaFayette, the fifth child, was born

in 1834 and died in 1919, when he was 85, two years after he broke a

hip cutting ice on a pond. In those times, a broken hip was usually

a death sentence, but LaFayette didn’t think he could die right

away because he still had important work to do.

LaFayette

had incredible energy, Case says. He was 6 feet 3 inches tall, built

like a linebacker, and he would leap out of bed at 4 a.m. because he

couldn’t wait to get to work on his farm.

Still,

he probably wasn’t a match for his father, "iron man"

Isaac Funk, described as "tornadic and dynamic, 6 feet 2 inches

of solid muscle." Isaac broke the prairie sod to plant corn,

raised cattle and hogs and drove them to market, sometimes for

hundreds of miles. He was able to sit in the saddle for as long as

three days without sleep while driving livestock to market.

[to top of second column in

this section]

|

Cassandra

was no fragile prairie flower, either. It was said she could ride

and drive cattle better than any other woman in the area. Most of

her 10 children were born in one of two log cabins, the first one

measuring only 12 by 14 feet —

not as big as one of the rooms in the Prairie Home.

The Isaac Funk family did not move into its first frame home until

1841.

A

Methodist, Isaac was an ardent abolitionist who strongly supported

Abraham Lincoln for president. Lincoln is said to have called him

the most honest and forthright man he ever knew. Isaac, himself a

good hand with an ax, coined the name "railsplitter" for

Lincoln’s campaign.

Before

he died, Isaac accumulated 25,000 acres of fine Illinois land. He

became known as the "cattle king" because of the number of

animals he raised and took to market and his advanced methods of

breeding and raising quality livestock.

He

also found time to serve for a number of years in the Illinois House

of Representatives and in 1862 was appointed to the Illinois Senate

to complete the unexpired term of Richard Oglesby. He was re-elected

in 1864 and attended a session of the Senate on Jan. 14, 1865, just

16 days before his death. (He died on Jan. 30, and Cassandra

followed him three hours later.)

Isaac

was a firm friend of the Union and an enemy of the

"Copperheads," Northerners who sympathized with the South

during the Civil War. His famous Copperhead speech, given in 1863,

was widely reported in the national press and read to Union soldiers

all over the country. Isaac pulled no punches, calling them traitors

and secessionists who deserved hanging, and offering to fight with

any one of them in any manner they chose. He was 65 years old at the

time, but still so strong that when he spoke people could hear him a

block away, and when he pounded his fist on the table, the inkstand

bounded half a dozen inches into the air.

Like

his father, LaFayette was a man of many accomplishments. His full

name was Marquis De LaFayette Funk, in honor of the French general

who helped George Washington in the Revolutionary War.

He was

the first of Isaac’s sons to go to college, and he went to Ohio

Wesleyan because it had a program for scientific farming. (Isaac was

one of the founders of Illinois Wesleyan College in Bloomington.)

There LaFayette met Elizabeth, a gifted musician who lived in a

house that had been a station on the underground railroad.

They became engaged, and

he promised to come for her as soon as he built a home for her to

live in. She agreed to wait, though she probably didn’t think it

would take as long as 2½ years. But when she did get to Illinois,

she found a gracious, comfortable 13-room home, surrounded by rich

farmland, where she spent the rest of her life.

(To be continued)

[Joan

Crabb]

[Click

here for Part 2]

|

|

Back

to top |

News

| Sports

| Business

| Rural

Review | Teaching

& Learning | Home

and Family | Tourism

| Obituaries

Community | Perspectives | Law

& Courts | Leisure Time | Spiritual

Life | Health

& Fitness | Letters

to the Editor

|

|